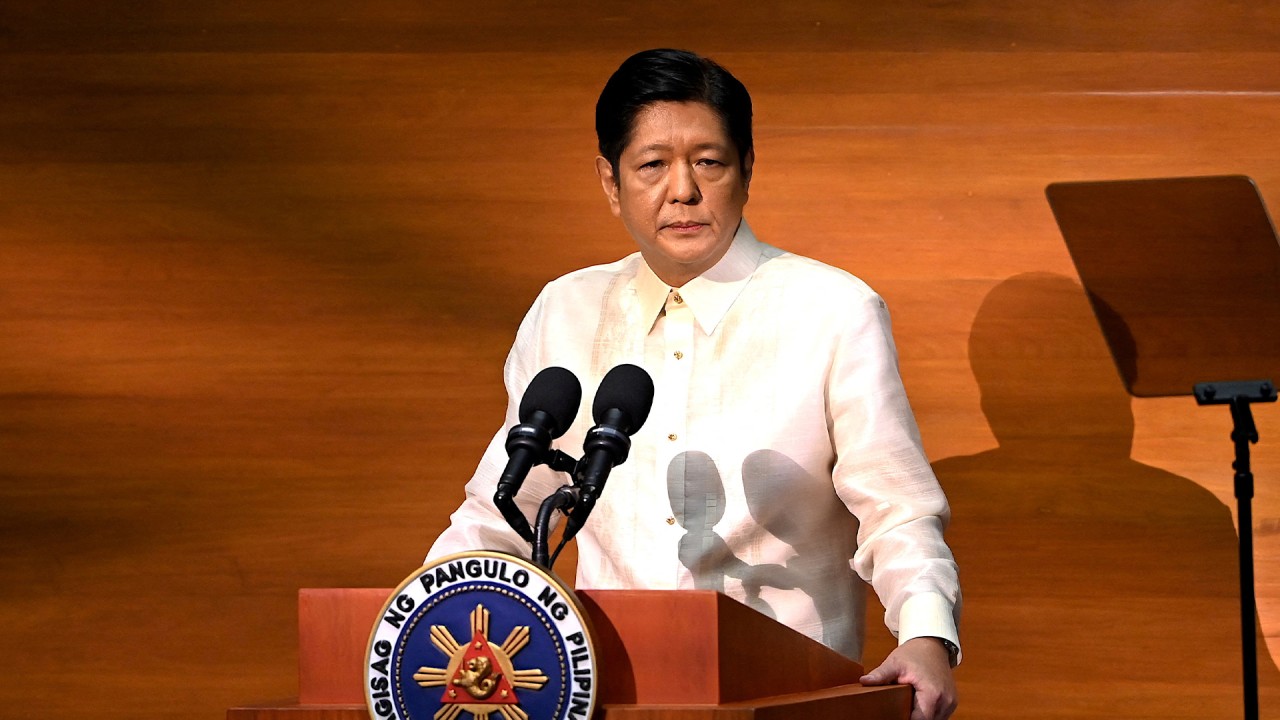

Will Philippines’ Marcos Jnr revive talks on China oil deal to solve looming energy crisis?

- The Philippines and China signed a memorandum of understanding for oil and gas cooperation in 2018, but talks were called off after negotiations failed to bear fruit

- Chinese interference and Manila’s inability to attract big oil players have hindered attempts to exploit energy resources in the West Philippine Sea

Rising demand, diminishing resources and a looming energy crisis may set the stage for reviving talks for a proposed joint oil and gas development between Manila and Beijing in the West Philippine Sea.

Senator Robinhood Padilla on July 21 filed a resolution urging for the resumption of bilateral discussions for possible joint development in the maritime hotspot.

Marcos’ work cut out for him, from Philippines’ energy crisis to China oil deal

The resolution came a month after former Secretary of Foreign Affairs Teodoro Locsin announced the termination of talks in a farewell speech a week before the Duterte administration bowed out of office to make way for the new Marcos government.

If the war in Ukraine, now in its fifth month, persists, the coming winter may exacerbate the global energy conundrum. This puts oil importers such as the Philippines in a vulnerable situation, increasing calls to harness local energy resources to reduce external dependence and enhance energy security.

Chinese interference and Manila’s inability to attract big oil players in its new offshore block offerings have long hindered attempts to exploit these resources. Beijing has previously protested against unilateral efforts by other claimants to explore and drill for oil and gas in the semi-enclosed sea. The only difference is that China now has the wherewithal to act on its displeasure.

As Manila’s largest natural gas field, Malampaya, located in the same waters, nears exhaustion, developing a replacement becomes urgent. Malampaya, which started commercial operation in 2002, supplies 20 per cent of the country’s energy requirements and is expected to run dry by 2027.

In his first State of the Nation address on July 25, Marcos said he would promote natural gas to diversify the country’s energy resources and complement variable energy obtained from renewables.

He promised to “provide investment incentives by clarifying the uncertain policy in upstream gas, particularly in the area close to Malampaya”. The nearby Sampaguita field in the Recto (Reed) Bank, 200km southwest, may hold the key as it is estimated to hold three times the deposit of Malampaya.

But this submerged feature has long been a bone of contention between Manila and Beijing. In 2011, a Philippine-sanctioned exploration ship operating in the vicinity was harassed by Chinese boats, an incident that affected bilateral ties. Such uncertainty and political risk discouraged interest in the prospective area.

Manila’s inability to guarantee foreign investment in these choppy waters and Beijing’s growing pressure on big international petroleum companies to disengage from upstream activities in the South China Sea with other littoral states impede efforts to extract energy from the Philippine seabed.

This is a setback for the Philippines as the dearth of local companies with deep pockets, industry track record, and technological capacity to engage in risky and capital-intensive offshore work make it reliant on outside players. Shell and Chevron, foreign partners in the Malampaya joint venture, have already left, selling their interests to a local conglomerate.

This is despite the ready market, existing infrastructure, and other promising offshore blocks close by.

Can the Philippines draw investors amid inflation, debt and corruption woes?

The Philippines is not alone in this predicament. Vietnam, another frontline claimant state in the South China Sea, is also feeling the heat. Spanish company Repsol last year sold its offshore assets, including its stake in the Ca Rong Do (Red Emperor) prospect in Vietnam’s EEZ, after its work in the area was disrupted by Chinese pressure.

There is also little progress in the long-delayed Ca Voi Xanh (Blue Whale) project by US energy giant ExxonMobil.

Hanoi has long invited energy players from countries like India, Japan, and Russia for sovereign and diplomatic backing, in the hope that China would exercise more prudence in dealing with the activities of state and private oil companies of major powers. But the viability of this approach is in question, given changing commercial and geopolitical considerations.

Coastal states such as the Philippines cite force majeure to suspend operations, extend the contract period and devise policy incentives. Still, such measures are not enough to keep wary investors who lose billions for every delay or interruption.

Many are unwilling to play the long game and are thus susceptible to foreign pressures. This is unsettling for several Southeast Asian states who are anxious about their big neighbour limiting their options. One of the reported sticking points in negotiations for a Code of Conduct in the South China Sea was Beijing’s desire to exclude companies from non-regional countries in the sea’s offshore projects.

Joint development was seen as a possible way out of the quagmire. If Beijing’s interest in the South China Sea is motivated more by security and geopolitics, then it may be open to giving more favourable concessions to its neighbouring littoral states to seal the deal.

The concept is enshrined in international law and there is abundant state practice. But it remains domestically unpopular, especially given rising nationalist sentiments among coastal states such as Vietnam and the Philippines. The 2016 arbitration award, which invalidated China’s historic maritime claims, presents a serious challenge.

Philippines will be ‘a good neighbour’ but won’t yield territory, Marcos says

Packaging an acceptable joint development that would not undercut the landmark award will require skill. Reconciling such cooperation with the country’s constitutional restrictions is another tough job, as the constitution reserves the use and enjoyment of the Philippines’ marine wealth “exclusively to Filipino citizens”, but also allows the president to enter into deals with foreign corporations on energy exploration and development.

Locsin alluded to this quandary, saying that dialogue with China “got as far as it is constitutionally possible to go”, but that a step forward could trigger a “constitutional crisis”.

Joint development plans have faced opposition. In 2004, a bilateral Joint Marine Seismic Undertaking in the West Philippine Sea, which became a tripartite undertaking with Vietnam’s participation the year after, was criticised and eventually discontinued.

Philippines’ new leader must keep South China Sea agreement with Beijing: Duterte

Last March, Duterte suggested his successor honour the joint exploration agreement with China to avoid possible conflict.

Marcos, who won almost twice as many votes in the presidential election as Duterte did in 2016, can make use of his mandate to explore a mutually beneficial compromise to solve the country’s energy problem.

During the 1970s oil crisis, China, then a net petroleum exporter, helped the Philippines by providing 1.2 million barrels yearly. Getting such critical supplies was also among the motives behind the decision of then leader Ferdinand E. Marcos Snr, the incumbent president’s father, to establish official ties with Beijing.

Marcos could follow in the footsteps of his father and restart talks with China for a favourable deal to get the Philippines out of the energy crunch.