How Philippines’ first sovereign wealth fund can succeed against all odds

- Mineral reserves can be tapped into and the revenue used to help fund public works, while the Philippines’ strategic location is another asset

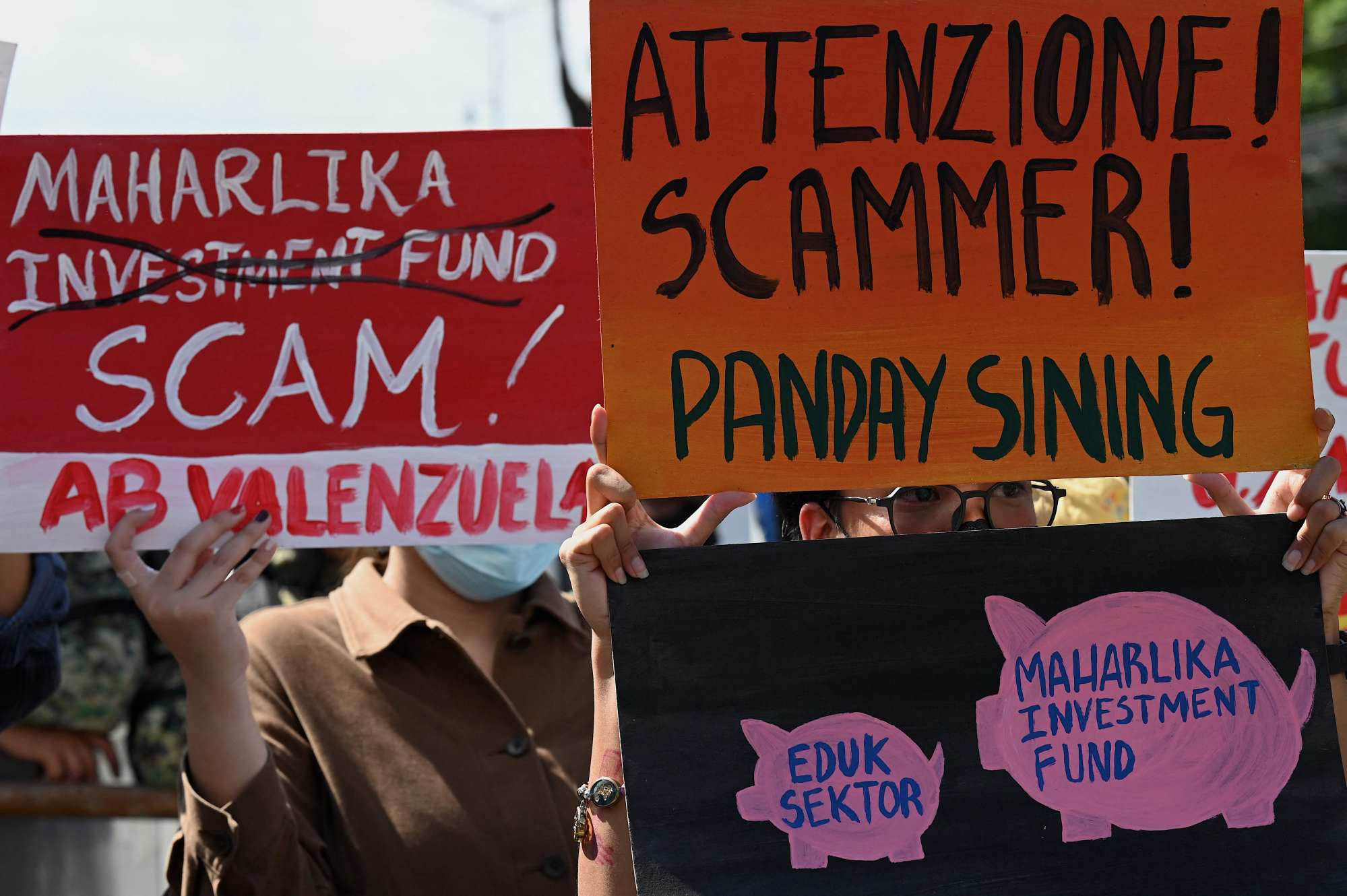

- But strong safeguards will be crucial, with critics saying the fund’s governance structure raises red flags and could expose it to political influence

In his second State of the Nation Address on July 24, Marcos Jnr said: “For strategic financing, some of the nation’s high-priority projects can now look to the newly established Maharlika Investment Fund, without the added debt burden.”

While mitigating the risks of a debt-fuelled infrastructure build-up makes sense, one wonders if all current options have been exhausted before a new layer is created. More favourable lending terms could be negotiated with external development partners. There’s also public-private partnerships to consider, or encouraging domestic banks – including those owned by the state – to invest in promising infrastructure.

Key criticisms of the MIF have centred around its funding and governance structure. The government’s decision to draw funds from state-owned banks and the country’s central bank may compromise their ability to raise capital and fulfil their respective mandates. Those with pension funds have also opposed the MIF touching their money for fear of misconduct.

To allay such criticisms, the MIF could instead look to other revenue streams to maximise its potential.

Philippines’ Marcos Jnr approves wealth fund bill, promising ‘utmost prudence’

The Philippines has the fifth-largest mineral reserves in the world, holding an estimated US$1 trillion worth of untapped copper, gold, nickel, zinc and silver. It’s already one of the world’s largest exporters of nickel and cobalt, metals critical to electric-vehicle batteries and renewable-energy technologies. The room for growth is immense.

The Cadlao and Linapacan oil wells in the West Philippine Sea are being redeveloped amid plans to harness offshore hydrocarbons from the Philippines’ western continental shelf. Developments in deep-sea mining could also unlock immense opportunities, as the mining and processing of minerals and fossil fuels can deliver funds for the MIF.

Meanwhile, the Philippines received only a modest US$100 million worth of investment in nine bases it has granted the US access to under the 2014 Enhanced Defence Cooperation Agreement. Of this, US$82 million was already allocated at the five original locations. In the late 1980s, the US was paying US$180 million yearly for Subic, Clark, and four other smaller outposts in its former colony.

As rival powers jostle to acquire prime lots in the Indo-Pacific, strategically-placed regional countries are driving hard bargains to seal good deals. The Philippines should be no exception. More than supporting the modernisation of its armed forces and developing its self-reliant defence programme, leases can also generate funds to underwrite civilian infrastructure projects.

Finally, good governance can make or break a sovereign wealth fund and spell either abundance or ruin for its host country.

All of the MIF’s regular and independent directors, as well as members of its advisory body, are presidential appointees. Critics argue that this exposes the fund to potential political influence, which may undermine public and investor trust.

The speed at which the MIF bill was passed into law gave the impression that it was railroaded while other, if not more, pressing priorities remained on the wish list. The president’s first cousin, House Speaker Martin Romualdez, did the job for Congress.

Philippine critics slam sovereign fund: ‘our children will be buried in debt’

There was also speculation about possible US influence over the new fund after Senate President Juan Miguel Zubiri put his name to the MIF bill while on a trip to Washington in June last year. Days before the MIF was signed into law, the government’s economic team went on an investment roadshow in the US and Canada with the MIF on the agenda.

Reliable alternative funding sources, good governance, and learning from best practices will ensure that the MIF delivers.

Lucio Blanco Pitlo III is a research fellow at the Asia-Pacific Pathways to Progress Foundation. He is also a Taiwan Fellow and Visiting Scholar at the National Chengchi University Department of Diplomacy.