Amid choppy South China Sea waters, Philippines and Beijing should boost dialogue to calm tense ties

- The Philippines has been absent from recent China-organised meetings such as the third belt and road forum, a sign bilateral ties have turned worrying in a short time

- Both sides should improve communication channels, dial down tensions and work on practical cooperation in the South China Sea

All these are now a distant memory as relations quickly turned worrying.

In a sign of how the South China Sea dispute is beginning to affect constructive ties, Marcos Jnr was absent from the third belt and road forum last month in the Chinese capital.

Unsurprisingly, talks about Chinese funding for three Philippine railway projects hit a snag. Economics should be insulated from disputes. The moment disputes spill over to economics is a time to reflect and review.

Philippine military races for sea change amid China’s rising maritime threat

Most disputants have been making headway in pursuing their interests in choppy waters discreetly and surreptitiously. There are clearly benefits to the latter approach.

The Philippines and China must therefore recognise the perils of allowing the situation to escalate further and work on dialling down tensions. They must stick to the message that maritime issues do not define bilateral ties, and improve communication channels with each other and their respective audiences. Both have to advertise the benefit of broader positive relations and highlight the potential for further gains if differences are managed well.

It is baffling for Manila to shun such venues when even the US is trying hard to boost dialogue with China, as seen in President Joe Biden’s meeting with Xi on Wednesday on the sidelines of the 30th Apec summit in San Francisco.

Issues of sovereignty, maritime rights, and jurisdiction take time to be settled, even among good neighbours. The Philippines-Indonesia EEZ delimitation took 20 painstaking years, and the continental shelf demarcation has just begun.

Furthermore, how can Beijing preclude Manila from upgrading its structures in the Spratlys when it had built a massive Great Wall of Sand while an arbitration case was under way?

Most of the Philippines’ oil and gas reserves are located offshore west of Palawan, the land mass nearest the Spratlys. The near exhaustion of Malampaya, the country’s largest and ageing natural gas field, is among Manila’s energy security problems, which are compounded by Chinese interference in hydrocarbon exploration.

From favourite to ‘forgotten’: Philippines’ sea dispute sees China pull funds

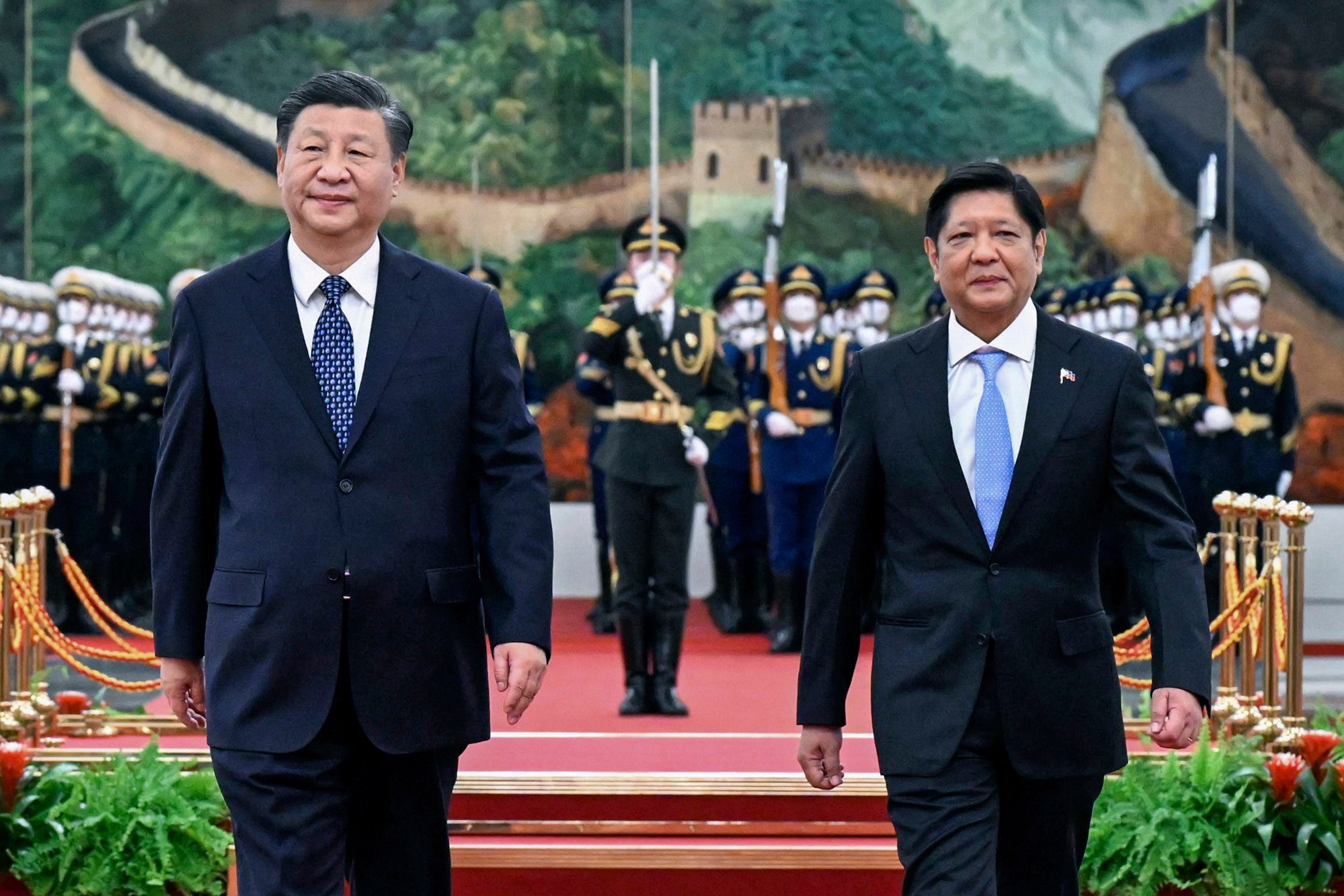

One of the agreements reached during Marcos Jnr’s Beijing visit was the establishment of a communication mechanism on maritime issues between the foreign ministries of both countries. This should be fully utilised. Philippine maritime authorities have been rather outspoken about the South China Sea dispute, and this may affect diplomatic efforts to ease tensions.

Manila in March hosted the seventh round of the vice-ministerial level bilateral consultative mechanism on the South China Sea. Both sides should explore convening the eighth iteration at the soonest.

Despite their seemingly intractable differences, the Philippines and China can still discuss practical cooperation in the South China Sea. A coordinated annual fishing ban can be tabled to conserve the sea’s diminishing fishing stocks to help depoliticise marine environment conservation. A multiparty joint fish stock assessment last year can serve as a precedent for further marine science cooperation.

The High Seas Treaty (BBNJ) can foster cooperation in the sustainable use of living marine resources, including in the high seas pocket in the middle of the semi-enclosed sea. Other areas of collaboration include ocean waves and offshore wind energy, mariculture and deep sea mining.

Maritime disputes do not define bilateral relations. Both sides should and could calm turbulent waters, steer bilateral ties back to steady ground and contribute to regional stability.

Lucio Blanco Pitlo III is Research Fellow at the Asia-Pacific Pathways to Progress Foundation.