Analysis | Philippine election: is Marcos’ win a sign of nostalgia for his father’s strongman rule?

- His emphatic victory spotlights the dynastic rule by scions of Asian strongmen such as South Korea’s Park Chung-hee, Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew and Indonesia’s Sukarno

- People seem to be attaching more premium to stability and decisiveness amid toxic domestic politics, demands for post-pandemic recovery, and global geopolitics in flux

The 64-year-old’s landslide win has rekindled memories of his father Ferdinand Marcos Snr’s rule from 1965 to 1986. Part of that tenure involved a 14-year martial law period that began in 1972 – a polarising chapter in the country’s history.

Philippines’ Marcos sweeps to landslide win, in reversal of family’s fortunes

Nonetheless, as is the case with eras of authoritarian rule, Marcos Snr’s martial law was also associated with widespread human rights violation, corruption, huge foreign debt, and an extreme dearth of democratic norms.

Asian scions

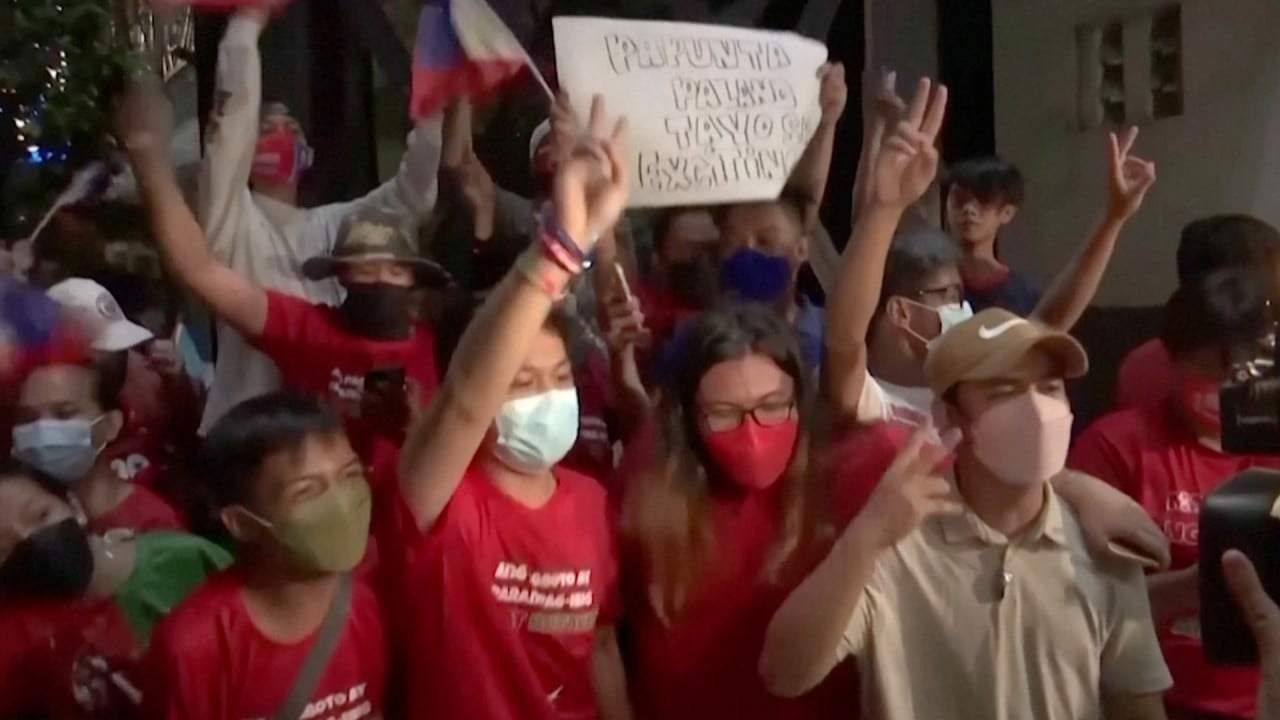

The scale of Marcos Jnr’s victory – a lead of 16 million votes over his closest rival Leni Robredo – suggests many Filipinos may have been mulling this convoluted chapter of their national history. Such introspection has been seen elsewhere in the region, in places that have also put in power the scions of ex-strongmen.

While the rule of strongmen often is accompanied by the prospect of unchecked power being abused, history suggests many in Asia seem to have profound reviews of these authoritarian pages in their nations’ chronicles, and the personalities associated with them.

Cultural Revolution was a catastrophe and Mao was responsible: CCP statement

Mao Zedong, the founding father of the People’s Republic of China, today is credited for defeating warlords, unifying the country and turning a revolutionary party into the country’s undisputed governing authority – a status quo that has now prevailed for seven uninterrupted decades.

In Taiwan, is another member of the Chiang dynasty on the rise?

He was also a recognised leader of the Non-Aligned Movement, hosting the 1955 Bandung Conference of Asian and African countries that eschewed getting pulled into the US-USSR Cold War.

Dynastic succession

Like his counterparts in South Korea and Indonesia, Marcos Jnr will complete a dynastic succession that took over three decades in the making.

In the case of Marcos Jnr, his ascent to power was a journey that took 36 years to happen. It was the same waiting time for former Philippine President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, who likewise assumed the top post of the land, echoing the service of her departed father, Diosdado.

What’s behind the Philippines’ love for political princelings?

Marcos Jnr’s run rides on the growing nostalgia and desire for strongmen.

People seem to be attaching more premium to stability and decisiveness amid toxic domestic politics, demands for post-pandemic recovery, and global geopolitics in flux.

The return of a Marcos Jnr to the pinnacle of power also underpins strong social undercurrents – of people wanting to reflect on their tortuous past.

As the nation celebrates the 50th anniversary of the declaration of martial law, will the hatchet be finally buried? Does the son’s triumph augur an emerging consensus that accounts for both the achievements and failings of the father?

If Marcos Jnr’s mandate underpins a country’s willingness to move forward, will he rise to the occasion and be the unity leader he bills himself to be?