Steel sector's plight illustrates extent of China's challenges

Over the last 10 years no industry has epitomised China's boom as well as its steel sector.

And today no other industry so neatly illustrates the problems facing China's economy, nor why they will be so difficult to overcome.

China's economic emergence has been built on steel. As the country has built factories, power stations, airports, shopping malls, railways, ships, cars and new homes by the million, demand for steel has soared.

According to the World Steel Association, China's mills turned out 128 million tonnes of crude steel in 2000. By last year that amount had surged fivefold to 683 million tonnes. This year the industry is on target to produce 713 million tonnes.

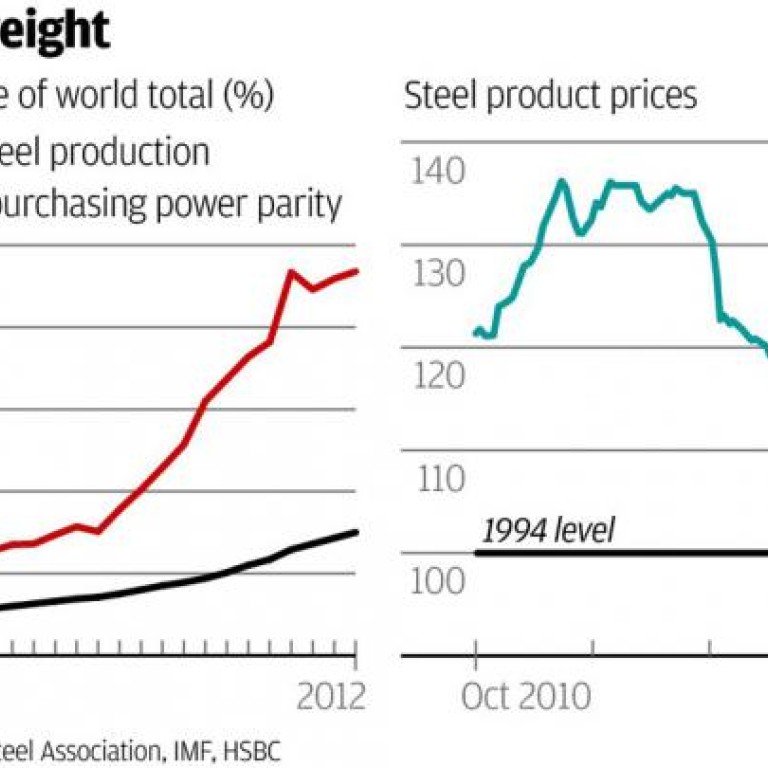

As a result, as the first chart below shows, China's share of world crude steel output has leapt from 15 per cent back in 2000 to 47 per cent in the first nine months of this year.

But that explosion in steel production is only part of the story. In 2005 the estimated that China's steel industry had more than 50 million tonnes of excess capacity. Today, according to a report on the sector published yesterday by Zhang Zhiming, head of China research at HSBC, the sector boasts a production capacity of 900 million tonnes, almost 200 million tonnes more steel than it is expected to turn out this year.

The reason capacity growth has so far outstripped actual production is simple enough. Local governments in provinces across China look to the steel companies they control to drive growth not just in gross domestic product and employment, but also in their own revenues.

Because of a historical quirk, local governments tax steel companies on their output rather than their profits. As a result, local officials have had every incentive to encourage investment in new capacity, given that since 2006 the sector has provided them an average 80 billion yuan (HK$98.49 billion) a year in tax revenues.

And there has been plenty of cheap financing to fund the expansion. Because China's steel companies are state-controlled, the banking system has long regarded them as backed by an implicit guarantee and has happily granted them around 1.2 trillion yuan in outstanding loans.

Meanwhile, the steel companies have also borrowed enthusiastically in China's corporate bond market, raising 75 billion yuan in the first nine months of this year. As a result, according to HSBC, the total liabilities of the country's biggest 80 steel plants reached 2.8 trillion yuan in June, equal to 6 per cent of China's GDP.

That's a problem, because even as steel output has soared, demand for the metal is falling.

By far the biggest consumer of steel in China over recent years has been the property sector, accounting for 38 per cent of demand. Next comes infrastructure construction, followed by demand for machinery, cars and shipping.

Government efforts to cool the property sector have badly eroded construction demand, and the slowdown has been compounded by cooling industrial production and the slump in shipbuilding.

As a result, sales of steel products fell by a third over the first eight months of 2012, and prices have collapsed back to 1994 levels (see second chart).

That's wiped out industry earnings. According to HSBC, 40 per cent of China's steel companies are losing money, with the sector as a whole recording losses of 21 billion yuan in the first half of 2012.

Losses on such a scale are going to eat into the ability of steel mills to service their debts, threatening a rush of defaults and a sharp rise in bad loans.

Clearly a drastic restructuring of the steel industry is essential.

But observers have been saying that for years. Reform efforts have always stalled in the face of powerful and well-entrenched political opposition.

There is little reason to think this time will be any different.