The world’s paying too high a price for inequality … and it needs to be addressed quickly

- Joseph Stiglitz believes a vicious spiral has been created because of the economic inequality

- Economic inequality translates into political inequality, which leads to rules that favour the wealthy, which in turn reinforces economic inequality

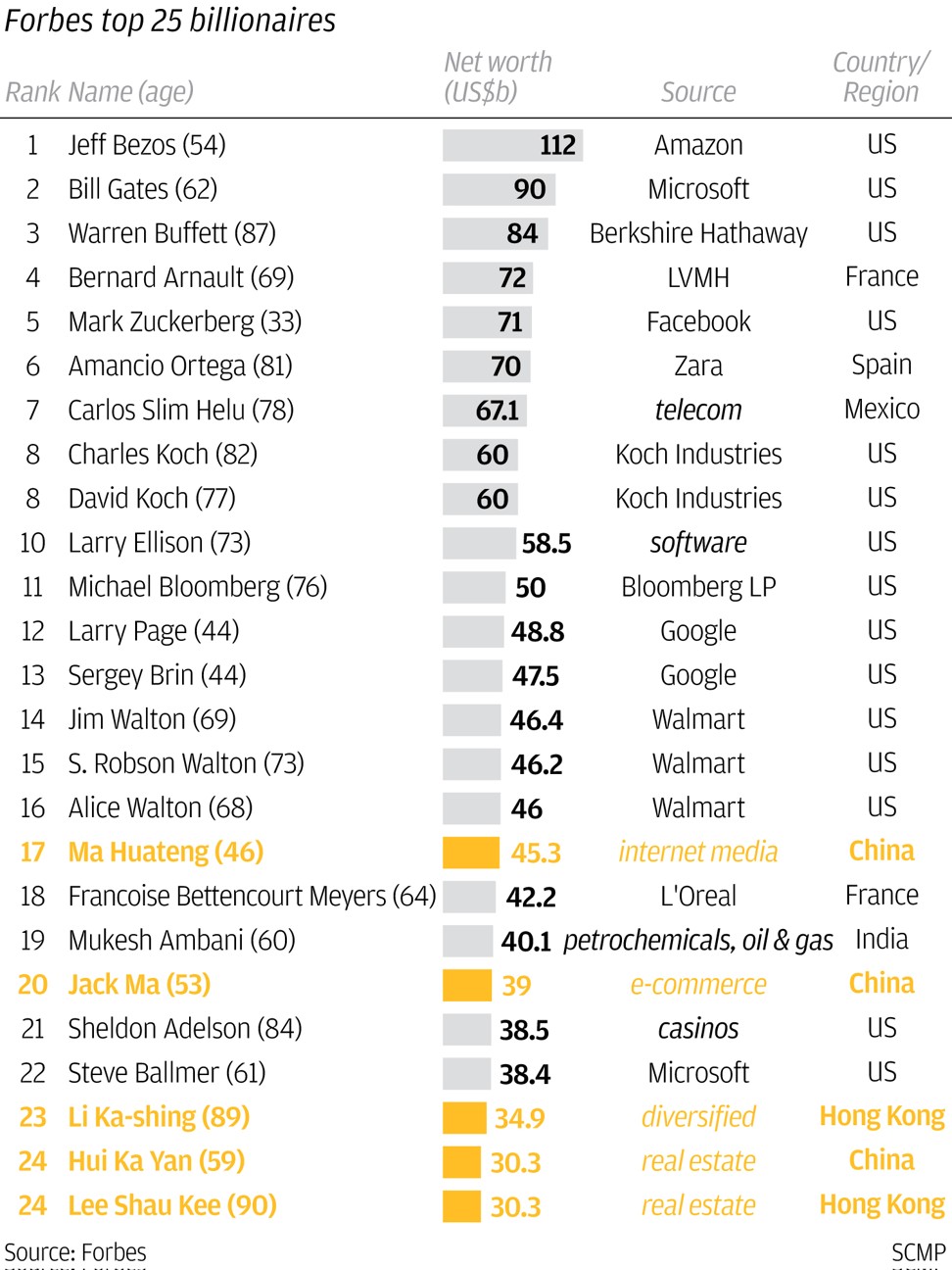

Joseph Stiglitz at Columbia University reminded us in the Scientific American this month that just three Americans – Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates and Warren Buffett – account for more wealth than the entire poor half of the US population.

As I watched the six pallbearers bringing Walter Kwok Ping-sheung’s coffin out of St John’s Cathedral last Thursday, I wondered what share of Hong Kong’s wealth they accounted for. Maybe not half, but probably not far short.

As Donald Trump stirs his base ahead of midterm elections with fearmongering over a raggle-taggle band of would-be immigrants wandering through the Mexican countryside towards the US border, claims of victimhood in international trade, and the rise of a modern yellow peril, one has to wonder what has happened to the issue that is truly eating the US from within – extreme and entrenched inequality.

As Stiglitz noted in the Scientific American: “By most accounts, the US has the highest level of economic inequality among developed countries. It has the world’s highest per capita health expenditures yet the lowest life expectancy among comparable countries. It is also one of a few developed countries jostling for the dubious distinction of having the lowest measures of equality of opportunity.”

While the income share of America’s top 0.1 per cent has quadrupled over the past 40 years, the income share of the top 1 per cent has doubled, and that of the bottom 90 per cent has declined. How can it seem reasonable that the average US CEO earns more than 300 times what the average worker earns, or in the UK that the average FT 100 CEO earns 229 times?

This has generated a sense of stagnation and relentless struggle for most middle class Americans in a setting where evidence of wealth inequality lies tantalisingly in plain sight all around. And yet the US administration is wholly silent on the subject – as are Trump’s counterparts in so many countries in Europe.

Here in Hong Kong, lip service is being given to the subject as so many youngsters join populist protests over poor access to good jobs, and even poorer prospects of ever owning their own home. But where is the evidence of a meaningful discussion of the economic and democratic damage being done as a result of extreme inequality?

Before I protest too much, I should recall that in truth, we in Hong Kong are relatively lucky, no matter how tough life may feel.

According to data in former World Bank economist Branko Milanovic’s “Global Inequality”, published just over two years ago, to be part of the lucky “Top 1 per cent” that have walked away with most of the economic gains of the past two decades, you need to earn US$71,000 a year. That amounts to about HK$46,000 a month. Household income statistics show that over 23 per cent of Hong Kong families have household incomes above that level – compared to 12 per cent in the US, and 9 per cent in Japan.

Economists like Stiglitz have spent lots of time trying to work out why such extreme inequality has emerged in recent years. Some blame the emergence of new technologies that have undermined the need for low-skilled workers. Some have blamed globalisation and unscrupulous state-owned Chinese enterprises that have whisked work offshore. Some have blamed the shift to services, populated by female non-union workers.

But none of these reasons seem convincing. The sense is that “the rules of the economic game have been rewritten, both globally and nationally, in ways that advantage the rich and disadvantage the rest,” says Stiglitz.

“Perhaps the defining moment … was the 2008 financial crisis, when the bankers who brought the global economy to the brink of ruin with predatory lending, market manipulation and various other antisocial practices walked away with millions of dollars in bonuses just as millions of Americans lost their jobs and homes and tens of millions more worldwide suffered on their account.”

In short, Stiglitz and many others believe a vicious spiral has been created: “Economic inequality translates into political inequality, which leads to rules that favour the wealthy, which in turn reinforces economic inequality.”

It seems that at present there is not the political will either among our “dictatorships of the propertied class” to recognise or to address the harm being done by our indifference to inequality

Or as Branko Milanovic eloquently put it: “As the super-rich use wealth to secure political influence, so politicians respond mainly to the concerns of the rich, sowing the seeds of ‘dictatorships of the propertied class’ disguised in the garb of democracy.”

This is well illustrated in the US tax cuts introduced at the start of this year, which have brought such disproportionate gains to the country’s wealthy.

Interestingly, this “political capture” also seems to have played a part in allowing weak and damaging environmental regulations, as Prof James Boyce at the University of Massachusetts Amherst demonstrates: “When people who could benefit from using or abusing the environment are economically and politically more powerful than those who could be harmed, the imbalance facilitates environmental degradation. The wider the inequality, the more the damage.”

To tackle this dangerously widening inequality, Milanovic identified a set of important policy responses: protect economic growth; provide secure access to homes; invest in education and ensure wide access; invest in health and wellness services; use “sin taxes” to redistribute some of the egregious wealth.

I find it fascinating that in the current fiercely fought US midterm elections, almost no airtime is being devoted to such issues, but rather to Honduran migrants, being tough on trade, and the big China threat. Better Trump’s preference for “entertaining diversion” on international issues than any focus on the difficult challenges at home.

It seems that at present there is not the political will either among our “dictatorships of the propertied class” to recognise or to address the harm being done by our indifference to inequality.

But we ignore Joe Stiglitz’s warning at our peril: “We are already paying a high price for inequality. But it is just a down payment on what we will have to pay if we do not to something – and quickly.”

David Dodwell researches and writes about global, regional and Hong Kong challenges from a Hong Kong point of view