Withdrawal syndrome sparks anxiety for Fed

US Federal Reserve has to be wary of moving too soon, potentially jarring markets, sending interest rates higher and choking off credit

When do you take the addict off the methadone?

That’s essentially the dilemma facing the US Federal Reserve’s 19 policy makers when they meet in Washington this week.

Since the height of the financial crisis in 2008, the US economy and everyone with a stake in it have become hooked on the massive amounts of stimulus injected by the US central bank.

Now, though, consensus is building among policy makers that the time is nearing to adjust their US$85 billion-a-month asset purchase program, dubbed quantitative easing, but divisions remain over just when to start reducing the dosage.

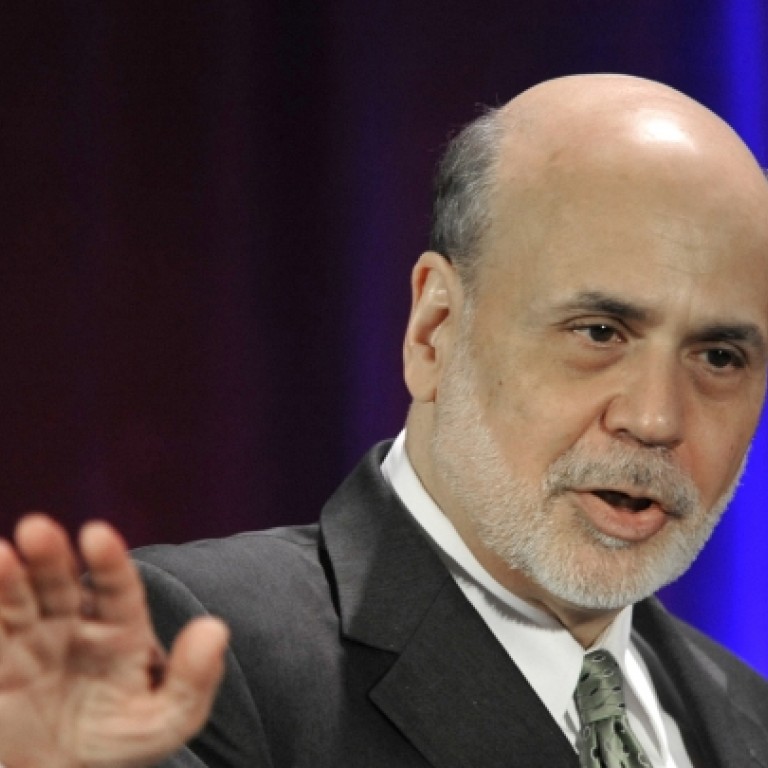

In recent weeks, even the program’s most ardent supporters, including Chairman Ben Bernanke, have begun signaling a willingness to dial back the pace of bond buying before too much longer. Meanwhile, those who have never liked it insist the moment has arrived and worry the Fed’s grip on markets is weakening the longer the program remains in full force.

“We haven’t taken steps in the face of better data to scale it back. So I worry that the markets believe we don’t have the capability or willingness to do that,” Philadelphia Fed President Charles Plosser told Reuters in a recent interview.

Indeed, the question of the market’s faith in the Fed has taken on added urgency in the weeks since Bernanke’s May 22 comment that the Fed could reduce the pace of its quantitative easing in the “next few meetings” sparked a global bond and stock selloff that continues to reverberate.

It is a delicate balance Bernanke and his colleagues must now strike. Moving too soon risks jarring markets, sending interest rates higher and choking off credit to a sputtering recovery.

They are trying to keep the interest rate policy and the QE separate. They’ve got this guidance language ...that is supposed to anchor that. Well, the anchor is slipping fast here

Still, it is also clear the centre of gravity in the debate at the Fed has shifted closer to support for a slimmer program, with Chicago Fed’s Charles Evans, centrist John Williams of the San Francisco Fed and dovish Boston Fed chief Eric Rosengren all growing warmer to the idea.

Some officials are eager to get away from the steady drip feed markets have come to expect in the hope this will break their habit of relying largely on guidance from the central bank, instead of shifts in the economy, to make their bets.

In this view, a policy meant to adjust dynamically to shifts in the economy has been held hostage to market expectations.

This week’s two-day Federal Open Market Committee meeting, which wraps up on Wednesday, is a critical juncture in the debate over the program’s future. While chances remain slim that the panel will vote to start the so-called tapering process now, the debate over that timing and execution will be in full swing.

Fed officials will discuss probable sizes of a reduction in bond buying, and what economic signals would merit a decision to ease off a bit.

One idea is to buy fewer Treasuries, while leaving in place the $40-billion-a-month purchases of mortgage-backed securities, which some officials believe are more effective in supporting the economy.

But as they gauge the economy’s readiness for a policy downshift, Fed officials don’t see eye to eye.

To St. Louis Fed President James Bullard, for example, inflation is worryingly low; to Kansas City Fed President Esther George, who like Bullard has a vote on policy this year, the bigger risk is a future rise in inflation.

But several of those closer to Bernanke’s inner circle see little risk on either inflation extreme.

At the Fed’s last meeting on April 30-May 1, Dallas Fed chief Richard Fisher pushed for an immediate tapering, while another official, most likely Minneapolis Fed President Naryana Kocherlakota, wanted to step harder on the policy gas pedal.

Most of the policy makers wanted evidence of continued progress from the economy before scaling back.

The shift in views toward a potential easing in the pace of bond purchases is being driven by this year’s sustained jobs growth, which has offered officials heart that the economy will emerge from its current fiscal policy-induced soft patch with a fair amount of vigor.

Still, there is widespread agreement that the economy is not ready yet. That means financial market anxiety - and the risk of a damaging spike in bond yields - is likely to build as the subsequent meetings in July and September approach.

A Reuters poll of economists on June 7 found that 42 of 48 expected the central bank to trim purchases before year-end. Of those, 21 said a reduction would likely occur in the third quarter; 19 specified September.

The gravitation toward a September exit date from earlier views closer to year-end circles back to Bernanke and his “next few meetings” comment during congressional testimony last month.

Some analysts speculate it was a deliberate move to shake up markets and remind them to pay attention to the economy.

If shaking up markets was the goal, it worked; the yield on the benchmark 10-year US Treasury note is near its highest level in more than a year and bond market volatility has spiked. From a record low on May 9, the Merrill Lynch Volatility Expectations index has jumped more than 55 per cent.

Goldman Sachs Chief Executive Lloyd Blankfein suggested last week that slightly edgier markets may be just what the Fed wants to recalibrate monetary policy expectations.

“If you want to handle that in the best way, you create a little bit more uncertainty in the market,” he told an event sponsored by Politico.

By lifting bond yields now, it could make an eventual trimming of bond purchases easier, while taking a little steam out of frothy markets. But it also carries the risk of disabling an economy fighting its way through a soft patch.

“It’s created a lot of confusion in the market,” said Scott Anderson, Bank of the West’s chief economist and chair of the Economic Advisory Committee of the American Bankers Association, which meets regularly with Fed policymakers. “When I look at the economic numbers, I just don’t see it yet, I just don’t see the strength in the labour market that would require a scale back.”

Just as Bernanke drove up expectations for a near-term reduction in bond buying, his comments sparked bets that the Fed would raise interest rates sooner than had been anticipated.

Before he spoke, interest rate futures markets were pricing in the first rate hike in April 2015. Early last week, they had October next year. By Friday, they had moved back to January 2015.

Even that may be early.

Fed officials have said they do not plan to even consider raising rates until the unemployment rate, now at 7.6 per cent, falls to at least 6.5 per cent, as long as inflation does not threaten to go much above their 2 per cent target.

Based on the latest Fed forecasts, unemployment isn’t likely to fall that low until well into 2015. The central bank will release new forecasts on Wednesday.

“They are trying to keep the interest rate policy and the QE separate,” said Ethan Harris, chief US economist at Bank of America-Merrill Lynch. “They’ve got this guidance language in there on the interest rate that is supposed to anchor that. Well, the anchor is slipping fast here.”