How the debt bubble burst for China’s Huishan Dairy

Troubled operation, estimated to be US$5.8 billion in debt, is pinning its hopes of survival on a ‘White Knight’ and/or a government bailout – although many industry insiders consider neither will be enough

A missing treasury head, a mysterious 85 per cent stock plunge, resignations of half of its board members and a billionaire tycoon chairman most of whose wealth evaporated in 1.5 hours.

All of these have combined to create what has become an unfolding drama engulfing China’s largest dairy farm operator, China Huishan Dairy Holdings, whose crisis has exposed a gigantic debt overhang looming over corporate China.

Before its remarkable March 24 share price crash, by a record 85 per cent in 90 minutes, Huishan had been one of the most “stable” stocks in Hong Kong, hovering around a narrow range between HK$2.75 (US 25 cents) and HK$3.17 for nine months.

Now it find itself firmly stuck in a debt quagmire.

It is pinning its hopes of survival on a “White Knight” and a government bailout, though industry insiders consider neither enough to help it remain on life support, at least by the deadline its chairman Yang Kai has laid out.

In the latest twist, a Shanghai court has frozen some company assets as requested by a wealth management firm, and a major peer-to-peer lending platform told the South China Morning Post it planned to sue. HSBC, on behalf of five other banks, last week alleged in a letter the dairy firm has defaulted on a US$200 million loan.

“This is yet another shoe to drop in Huishan saga and we expect there will be more,” Muddy Waters said in a statement to the Post.

“Huishan’s black hole of debt will scare off investors, while government intervention is not in favour in Beijing,” said Shen Meng, an executive director with boutique investment bank Chanson & Co. “The policymakers’ agenda now is to push dodgy companies into natural foreclosure.”

The city’s investment community have long cast doubt over the dairy giant’s audacious borrowing and all-too-frequent chairman share buybacks since 2015, but few ever expected its stock to crash that fast, and by that much, several Hong Kong-based fund managers told the Post.

Unlike typical penny stocks, Huishan counts a band of prominent institutional investors as shareholders, from Blackrock and Vanguard to Japan’s Government Pension Investment Fund.

Until now, it is still one of the biggest taxpayers in the Chinese northeastern rust belt province of Liaoning, employing over 40,000 workers in a region celebrated for its fake economic data and high jobless figures.

“It is a ubiquitous label in northeast China, and is the pride of the Liaoning government,” said Song Liang, an independent dairy analyst. “It may fall into the category of companies that are ‘too big to fail’.”

The Huishan saga first kicked off with the disappearance of Ge Kun, Yang’s right hand woman who has served with the company since her early 20s, until most recently, overseeing finances and cash operations.

It was at that point the dairy mogul was told of the company’s perilous finance position, a cash crunch that had effectively left it on verge of defaulting.

Yang was swift, however, to seek aid from the Liaoning authorities, and organised a meeting with at least 23 of its creditors, the day before the unexplained stock fall.

He admitted his firm was facing a “cash shortage” and government officials called on lenders to “give Huishan more time” and “not to file related lawsuits,” according to creditors who attended the meeting.

“It seems like the provincial government is fending off creditors so Huishan can get a ‘White Knight’ to assist,” said Robin Yuen, a consumer analyst with RHB Securities.

The government helped set up a creditor committee, conceivably as a step towards restructuring the debt, and Yang vowed to land a 15 billion yuan (US$2.18 billion) lifeline by introducing new investors, with the deadline set on April 23.

Being dragged into its financial woes are some of Asia’s top lenders, including ICBC, Bank of China, Bank of Communications and HSBC, the London-based giant being among the first to declare Huishan’s official default last week, in its case a US$200 million syndicated loan.

Banks in northeast China, a region used to suffering from economic malaise, are no strangers to heavy political interference.

Fearing massive layoffs and shrinking fiscal revenue, local officials have often forced lenders to write of credit losses in order to avoid liquidations and bankruptcies of leading local employers.

In return, they get to maintain political relations vital to doing business in a country ruled by state capitalism.

According to estimates by ICBC, Huishan is 40 billion yuan (US$5.8 billion) in debt, or 1.38 times the liabilities of the country’s two biggest dairy companies combined – Inner Mongolia Yili and China Mengniu Dairy.

“It is likely that banks will extend their loans for about a year,” Shen said.

“None of them are happy to see Huishan break down because once the company gets wound up, all the loans will become bad loans and will look ugly on their balance sheets.

After the company’s stock crashed, Hongling Capital – a leading Chinese peer-to-peer lending platform – revealed it had lent 50 million yuan to Huishan on an annualised interest rate of 13.5 per cent.

Documents seen by the Post show the dairy firm also sold debt as “investment products” to retail investors, on a small finance exchange in north China.

“Big banks may not be in a rush, but creditors like asset managers, peer-to-peer lending platforms have bigger incentives to get their money back, at any cost regardless of what the government says,”said Shen. “Smaller players can’t afford to bear the brunt.”

Despite Liaoning government’s call for time, Gopher Asset Management, a Shanghai creditor, has already resorted to legal action, applying to a Chinese court to freeze Huishan and its chairman’s cash or equivalent assets worth 546.1 million yuan.

The opaque nature of China’s shadow banking world, where credit is channelled in the form of “wealth management products” means “nobody knows exactly how much money Huishan has borrowed,” Shen said. “And how much it is able to set aside now.”

The troubled dairy company is among tens of thousands of enterprises whose thirst for credit has played a big part in China’s ballooning debt.

Big banks may not be in a rush, but creditors like asset managers, peer-to-peer lending platforms have bigger incentives to get their money back at any cost regardless of what the government says. Smaller players can’t afford to bear the brunt

Bolstered by the government’s massive credit-led economic stimulus programme since the Global Finance Crisis of 2008, the country’s corporate debt has soared to 169 per cent of GDP, according to figures from the Bank for International Settlements, with a rising tide of defaults.

That adds up to potentially huge difficulty for the cash-strapped Liaoning government, which gained global notoriety in January by admitting to have inflated its GDP figures, to orchestrate a successful Huishan rescue.

In October, Dongbei Special Steel, a majority-owned Liaoning province state firm, formally filed for a bankruptcy restructuring process, on a court ruling, after it had missed payments on bonds nine times.

Debt holders were so frustrated at one point that they threatened to impose sweeping financial sanctions against Liaoning itself – a sign that financial institutions now may not honour the “political capital” they would gain in helping troubled state firms in the Chinese rust belt at the expense of the health of their balance sheets.

Huishan’s chairman Yang may also find it impossible to live up to his promise to tackle the cash crunch with his 15 billion yuan liquidity boost in four weeks, as few are willing to take over such debt burden at the depth of its chaos, experts believe.

China National Cereals, Oils and Foodstuffs Corporation, or COFCO Group, which owns Mengniu, as well as a number of dairy companies and private equity firms are believed to be in talks about investment, but it would be “extremely hard” for any interested parties to reach a deal by the April 23 deadline, people with knowledge of the matter have told the Post.

“The entire dairy industry has yet to fully recover from plunging milk prices, so I doubt that either Yili or Mengniu is able to set aside cash sufficient to save Huishan within such a short period,”said Song, the dairy expert.

“To achieve that goal, Yang has to approach a big group of potential investors in and out of the dairy industry.”

In October, Yili, China’s largest dairy company, agreed to buy Hong Kong-listed organic milk producer China Shengmu for US$678 million, while Mengniu offered in January to pay US$826 million for another Huishan rival, China Modern Dairy.

Those effectively rule the companies out of splashing more on any stake in Huishan, though analysts suggest the indebted firm’s assets – essentially tens of thousands of cows and milk producing plants – still look appealing.

The strongest name to emerge from the shadows as a possible white knight is COFCO Group, China’s largest food processing, manufacturer and trader.

“It would make sense for COFCO to acquire assets from Huishan,” RHB’s Yuen said. “COFCO could take over the shares, but that may seem messy.”

From farm worker to Liaoning’s richest man in four decades

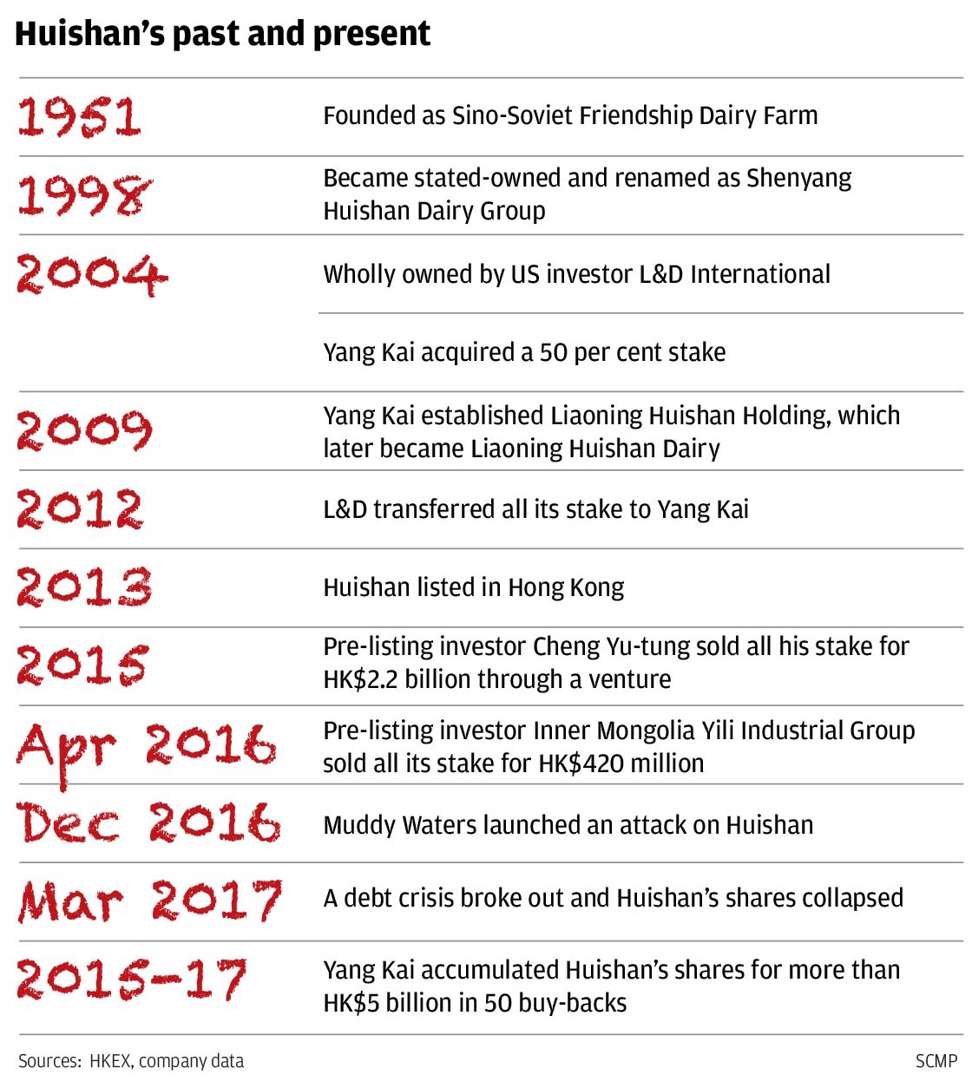

Huishan Dairy’s chairman Yang Kai’s road to success proved circuitous, as he spent more than four decades turning himself into the richest person in Liaoning province.

But the more than 20 billion yuan (US$2.9 billion) fortune he amassed evaporated in just less than two hours on March 24, when Huishan Dairy’s H-shares plunged 85 per cent.

Born in 1957, Yang was sent to Kangping county, Shenyang to experience the grinding poverty of the rural poor working on the land, according to the Beijing News.

Four years later, he started at a state-owned flour factory in Shenyang before he was transferred to another state-owned company making food-processing machines in 1984.

By 1992, though, he was a major shareholder with a Chinese business partner, and general manager of the Sino-US joint venture, Shenyang L&D Cereals & Foods.

In 2004, he then bought a 50 per cent stake in Liaoning Huishan Dairy, which was wholly-owned by US investor L&D International.

Liaoning Huishan Dairy, formerly known as Shenyang Dairy, was a state-owned enterprise bought out by L&D in 2002 when the local government carried out a series of reforms to privatise and revitalise the ailing SOEs.

L&D sold its remaining stake in Huishan Dairy to Yang in 2012.

He was listed as the richest individual in the northeastern province of Liaoning.

Known for his nimble skills in asset manoeuvring and fundraising through leverage, Yang announced in 2015 that his dream was to create the most-trusted dairy brand in China.

Daniel Ren and Celine Ge