First team to kayak Arctic’s Northwest Passage finds more than just world records and numb feet in epic adventure

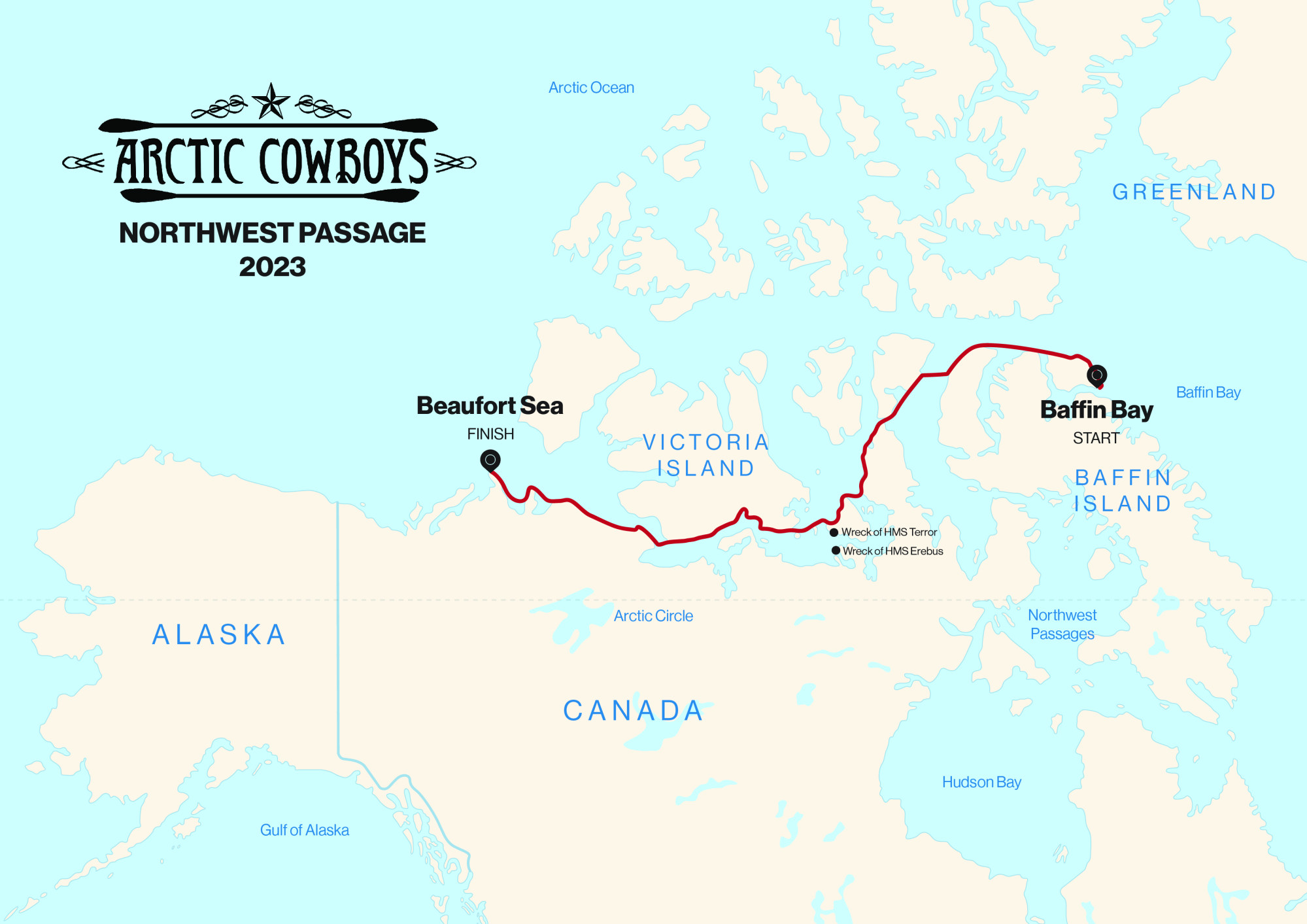

- Mark Agnew, Eileen Visser, West Hansen and Jeff Wueste become first team to kayak from Baffin Bay to Beaufort Sea

- Quartet navigates sea ice, freezing temperatures, while covering ultramarathon distances day after day, and Agnew still can’t feel his feet

It is hard to believe that just two weeks ago I was standing in a remote region of the Arctic, staring at the sky waiting for a plane to pick me up after 103 days of suffering, camaraderie, unique and wonderful moments.

The culmination of years of work, three teammates and I had just set two world records kayaking the entire Northwest Passage.

We had thrown rocks at a polar bear as it pressed itself against our tent. We’d narrowly escaped a painful death when two huge bits of floating ice collided, with us in the middle.

We’d see the Northern Lights, narwhal, bowhead whales and beluga. We’d covered ultramarathon distances by kayak for days on end and spent an equal amount of time trapped in our tent by storms. My feet still sting with cold and the doctor says I should expect full sensation to return in a matter of months – I last felt my toes on July 2.

We were the first people to kayak the fabled route, and the first to do it under human power, in any craft, in a single year. These were world firsts, sought after by the adventure community for at least a decade – even this year there were two other rowing teams attempting the same feat.

Martin Frobisher first searched for the passage in the 1570s and it took almost 300 years before it was finally found by John Rae in the 1850s. It took another 50 years for Roald Amundsen to be the first person to make it through. As the ice retreats because of climate change, adventurers have been dreaming of becoming the first to make it through by human power, with no sails or motors.

I called the Northwest Passage by human power the “last great first” and concluded that because the ice was retreating “history beckons for one final effort for the centre stage of the age of exploration, 100 years after everyone thought it was over”.

By the time I started, my motivations were routed in more than just gaining a world record or two. I was determined to have an immersive experience in nature and to build deep bonds with my teammates – Americans Eileen Visser, West Hansen and Jeff Wueste.

I frequently gives talks to schools, companies and other audiences, and this is part of the journey I always emphasise – do not focus on a single outcome, you need intrinsic motivations too, which allow you to judge success on your own terms. The journey would not have been the same if the only thing I wanted was my name in the record books.

I got the immersive experience I was looking for. In fact, at times it was maybe too immersive.

On one occasion, after paddling for almost 11 hours, sea ice floated in from another part of the passage. It filled every inch of the water around us. It flowed and spilled over itself like lava. Although we were less than four miles from shore, a distance that would usually take an hour, it took us eight hours to reach land.

We frantically paddled back and forth looking for an opening. We eventually found a break in the ice, not big enough to get to land but big enough for a rest. As we bobbed around, contemplating our predicament, two massive bits of ice changed direction and started to close in around us.

Jeff and West managed to paddle out of harms way but Eileen and I were stuck. With a sickening crunch the ice collided. It should have crushed us to death.

By some miracle, the pressure lifted us, like squeezing a bar of soap that slides up out of your hand. We popped out on top of the two bits of ice, pulled ourselves forward and plunged back into the water.

But the danger wasn’t over. The little space that remained was closing too. I leapt out onto a flat bit of ice, hauled our kayak onto it, then grabbed the other kayak just as West and Jeff were being capsized by the moving ice and hauled them up too.

We sat on our new floating home and waited until enough space reappeared and we made a mad dash for shore. We’d been kayaking for 18 hours.

Challenging as it was, it was the most memorable and enjoyable day of the expedition. It was just one of many tough days.

So when we finally finished the passage on October 8, I cried and cried and cried, and then had to paddle another 16 miles to a campsite, wait out another storm, dig our tent out from under the snow in the pitch dark and kayak a final 32 miles to an abandoned airstrip to get picked up.

The world firsts we’d achieved felt monumental, but they were just one of the outcomes I sought. The experiences we had, and more importantly the experiences we shared, will live with me forever.