In embracing AI, Southeast Asia must consider sobering climate costs

- Landmark UN AI resolution linked to sustainable development goals should be a wake-up call for Southeast Asia to consider the true costs of adopting AI at breakneck speed

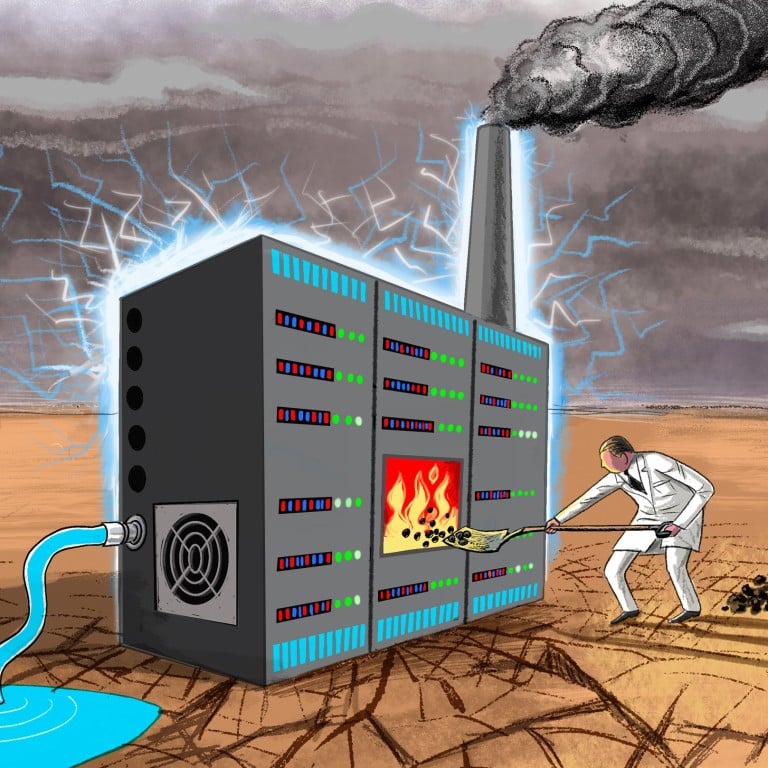

But deploying AI across a range of sectors is not without cost to the climate. Major AI applications and their supporting infrastructure, designed for redundancy and continual updates to meet client expectations, are notoriously resource-intensive.

Where water rather than air is used to cool data centres, several million litres per year can be channelled to a single data centre building. Google, which has three data centres in Singapore, reported water consumption of about 450,000 gallons per day for an average data centre in 2021.

This is to say nothing of the voracious computational power required for generative AI. One study estimates that training a single large language model (LLM) with 175 billion parameters could result in over 500 tonnes of carbon emitted, equivalent to burning over 551,038lbs of coal.

Indonesia’s emissions surge as Asia seeks more energy-intensive data centres

Put another way, it would take more than 8,200 tree seedlings grown for 10 years to sequester the amount of carbon produced by just one such LLM. Already, in 2018, OpenAI noted that since 2012, the amount of “compute” – processing power, memory and hardware resources – used in the largest AI training runs had been increasing exponentially, doubling every 3.4 months.

But resource consumption and carbon emissions are only part of the story. Other types of environmental impact, such as the toxicity of pollutants or effluents and biodiversity loss, are rarely, if ever, declared.

Additionally, it is worth noting that increased efficiency through AI may not have a net positive effect on the environment. It could even exacerbate harm in what some call the “rebound effect”. This is when savings of costs, resources and time through optimisation are transformed into increased consumption and its knock-on effects on the climate.

The UN resolution’s call for a life-cycle approach to AI is an important step towards an honest accounting of these systems’ environmental impact.

To borrow from internationally recognised standards (ISO 14040 and ISO 14044 for environmental management) and the UN International Telecommunication Union’s information and communication technology-specific life cycle assessment methodology, this could require assessing the entire spectrum of activities – from minerals extraction to system disassembly – and the generation of their own ecological and labour footprint across all 11 stages of the UN’s taxonomy for AI’s life cycle.

While corporations have embarked on “circular” initiatives, such as Microsoft’s plan to reuse 90 per cent of its cloud computing hardware assets by 2025, not all companies are able to do this. There are also reputational risks to weigh if there is to be a “full-stack supply chain” accounting of AI’s true ecological impact, including what conventional economics calls “externalities” – essentially third-party effects.

Yet, with 20 new data centres expected across Southeast Asia by 2027 in addition to the 242 in existence, a regional data centre market seen to grow by a compound annual rate of over 6.5 per cent between 2022 and 2028, and an emissions gap of 2.6-3.2 gigatonnes set against 2030 targets, a business-as-usual approach to a bigger-is-better AI would be surreally dissonant with the region’s climate exigencies.

After all, if OpenAI chief executive Sam Altman is right in predicting that AI will “change the world much less than we all think”, is it worth building fast and breaking things at the potential cost of an irretrievably scarred planet and humanity left off-kilter?

Elina Noor is a senior fellow in the Asia Programme at Carnegie Endowment for International Peace