Cultural compromise can help EU forge a new relationship with China

Lanxin Xiang says nation's future is aligned with that of a Europe at odds with US belligerence

The recent EU-China summit - the first between the European Union and the new Chinese leadership - indicates the beginning of a new, ambitious relationship. Although it has been labelled a "strategic partnership" for a decade, relations have always been on a more ad hoc basis, dealing with specific issues, mostly related to the economy and human rights. Now, finally, a clear road map has emerged in an unprecedented joint document charting bilateral co-operation through to 2020.

Trade and investment issues remain high on the agenda, and both sides have taken a big step forward by launching negotiations on an investment agreement covering protection and market access. But most notable are the tone of the dialogue and the much widened areas of co-operation, including regional security, energy and cultural exchanges.

Tremendous changes have taken place in both Europe and China over the past 10 years. In that time, bilateral relations have grown stronger. Today the EU is China's biggest economic partner, with bilateral trade in goods and services reaching almost half a trillion euros last year. As the notes, this has led to the creation of jobs and business opportunities for both sides . Pressing global challenges have also drawn the two closer on security issues.

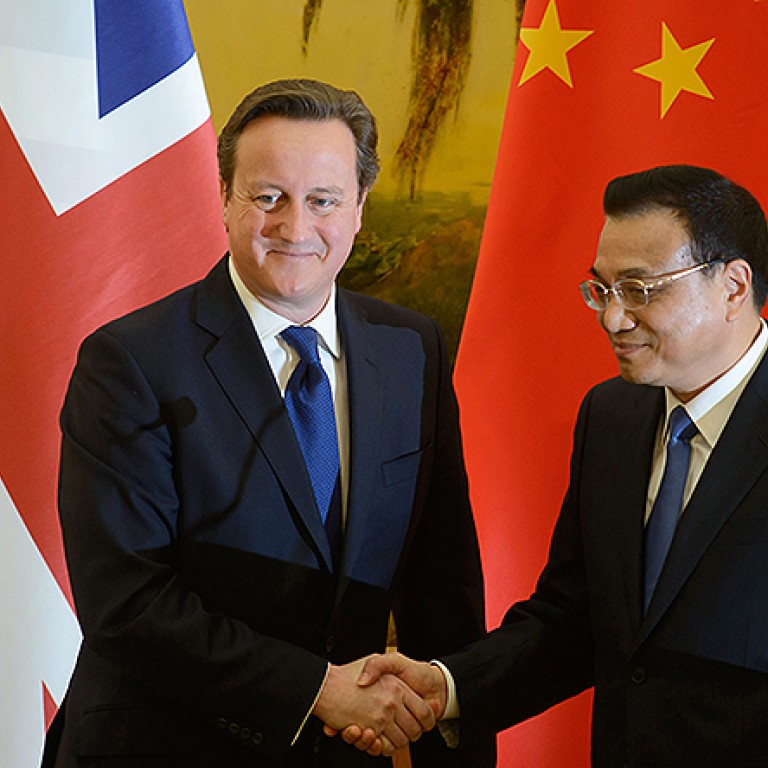

President Xi Jinping has described their relationship as two civilisations pushing for the progress of humankind. Meanwhile, Premier Li Keqiang said: "Any problem in China-Europe relations can be resolved as long as we increase communication and enhance understanding." This is the first time an official Chinese statement has raised EU-China relations to such a high level. It is in sharp contrast to Sino-US relations, where Beijing seems to be encountering many insurmountable problems.

The fact is that the EU and China have already become the key pillars of the international system; they do not place their trust and security in any residual unipolar system. With the end of the cold war, China's security concerns have shifted fundamentally, almost exclusively to the Sino-US relationship. This concern - in the form of the militarised US "pivot to Asia" - has compelled Beijing to pay close attention to the peaceful, rule-binding and multilateral EU approach to global governance.

Largely inspired by the European integration process, there has been a movement to create multilateral diplomatic and security mechanisms. For the first time in history, there is no major geopolitical conflict on the Eurasian mainland.

It is clear that China is now drawn into a continental orientation, because its long-term strategy involves the search for a safe environment for its economic and political development. The success of this strategy may ultimately hinge on civilisational compromise between the West and China, but not on naked international power politics.

The "West" is clearly divided. On one side is a Europe that is culturally tolerant of civilisational dialogues; on the other is the US, still running an "empire of denial", which could mean an ongoing global crusade against cultural challenges from other civilisations.

After all, Europe began the cultural debate with China some 400 years ago. It was the Catholic Church that first recognised the vast potential for expanding the Christian community beyond racial boundaries. Through a process of learning the customs, languages and thought patterns of targeted societies, the Jesuits attempted to restructure the Christian order according to local systems. A debate on whether Chinese ritual practices, such as ancestor worship, were in fact compatible with Christianity preoccupied missionaries for a century, and the eventual European rejection of the Chinese value system during this so-called "rites controversy" was a defining event in the history of the West's relationship with China. It also planted the seeds of a fundamental misunderstanding of China.

It is hard today to understand the extraordinary vehemence and bitterness surrounding this theological argument between China and the Christian world. Although it began as a theological debate, it eventually involved three popes, two Chinese emperors, hundreds of missionaries and the entire theologian faculty at the Sorbonne, the intellectual centre of the counter-reformation.

This first encounter is conveniently forgotten in the West. Hence, it falls upon the Chinese to put forward the idea of returning to the debate, which was relatively free from cultural bias and racial prejudice.

The EU also seems to have realised that its traditional approach to Asia is out of step with the continent's own trends. Asia is no longer interested in Western imports of values and institutions and the EU should abandon its efforts to transfer its own post-war solutions. Instead, it should focus on reviving the historical approach of cultural compromise and build influence on a more solid moral ground.