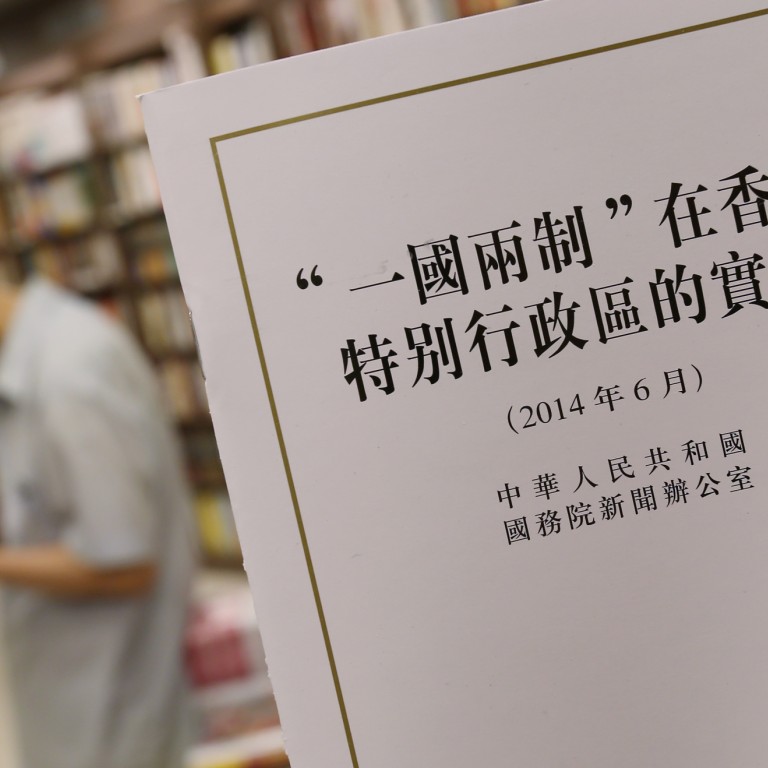

Overreaction to white paper on Hong Kong not supported by the facts

Mike Rowse says while its tone is strident, the words are nothing new

The Greek philosopher Plato is credited with being first to coin the expression, "Beauty lies in the eyes of the beholder". It is a pity he died so long ago as we could have used someone with his perspicacity to help us reach a fair judgment of the State Council's white paper on "one country, two systems".

The Bar Association and some political groups have attacked the paper, claiming it undermines judicial independence and seeks to claw back some of Hong Kong's high degree of autonomy. Zhao Ziyang's secretary Bao Tong was even reported as calling it a breach of the 1984 Sino-British agreement on Hong Kong's future.

The ferocity of this hoo-ha has caused me to go back and reread the whole of the Joint Declaration, and its appendices, and I have read the white paper no fewer than three times.

My conclusion is that much of the criticism of the white paper is greatly overblown. My copy of the English version runs to 36 pages: the first 22 cover the background of the Joint Declaration and the Basic Law, and all the developments in Hong Kong since 1997; the next eight pages deal with the juxtaposition of one country and two systems; the final six pages quote statistics and give sources.

It would be a valid criticism of the first section to say it looks at our first 17 years since the handover through rose-tinted spectacles. There is no mention of the great march of 2003 and the withdrawal of Article 23 legislation, for example. But governments are generally keener to talk about their successes than their failures. Who isn't?

But certainly it is a solid explanation of how the Joint Declaration gave rise to the Basic Law and it is unequivocal on the continuation of our legal system. "The common law and relevant judicial principles and systems previously practised in Hong Kong, including the principle of independent adjudication … continue to apply," it reads in one place. "When adjudicating cases, the courts of the HKSAR may refer to precedents of other common law jurisdictions, and the Court of Final Appeal may as required invite judges from other common law jurisdictions to sit in the Court of Final Appeal," it says later.

What the second section boils down to, in essence, is quite simple: "one country, two systems" is an integral whole. Our high degree of autonomy does not spring from out of the blue; it is derived from the Basic Law, which in turn came from the central authorities of the one country. It is patently true - some people just don't like to be reminded of it.

Most of the criticism centres on one part of the second section which talks about the executive, the legislature and the judiciary having some responsibilities in common. It is claimed this is tantamount to making judges part of the government, thereby destroying judicial independence. It does not.

The plain truth is that they are all part of the governing structure of our community. This is recognised in the West, which talks about a balance of powers between the three estates. In the US, it is the executive, Congress, and the Supreme Court.

We are approaching a very important tipping point in our history when we need to reach a consensus on how to move forward with political reform. It is a time for calm reflection.

It is right that we should be concerned to protect our freedoms and way of life, and alert to factors which might threaten them. But we should preserve our energy for real threats, not waste it tilting at windmills.