Advertisement

Advertisement

Behind China’s smiling diplomacy lies a growing military might, and its neighbours should be alert to the fact

Douglas H. Paal says China’s military moves since the 19th party congress should be a warning to its neighbours to stop thinking about their relationship with the rising power individually and start grappling collectively with the new regional geopolitical dynamics

Last week witnessed a mini media storm in India over a Chinese naval squadron purportedly headed to the Maldives to break with precedent and intervene in a power struggle there between the pro-Beijing president and a former president who leans towards India. The atmosphere was made more ominous by a warning in the nationalist Chinese newspaper Global Times, which told India that Beijing would not “stand idly by” if New Delhi intervened first. The storm then ended quickly when the Chinese squadron turned south and then back towards its home port, while the political crisis in the Maldives continues.

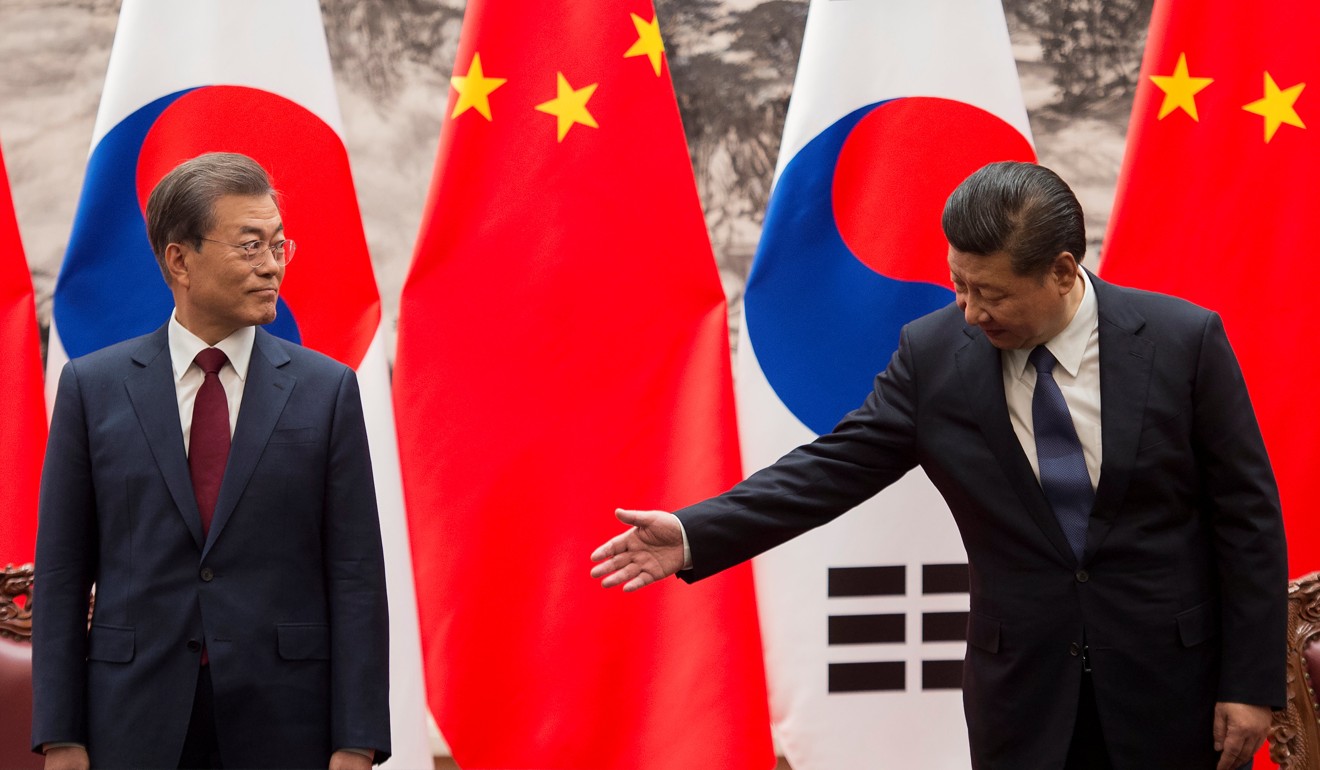

What should one make of this episode? Late last year, I wrote here about Xi Jinping’s new “smiling diplomacy”, seeking to manage differences with neighbours whose relations with Beijing have been troubled. Progress was recorded with Japan, South Korea, Vietnam and India soon after the 19th party congress. So what has changed?

China’s neighbours are welcome to have constructive relations with Beijing but they need to remember they are not dealing with the weak China of the past

But it must be remembered that Beijing’s new diplomacy is founded on a growing base of military power that Xi is also comfortable in deploying. In other words, China’s neighbours are welcome to have constructive relations with Beijing but they need to remember they are not dealing with the weak China of the past. China’s velvet glove of diplomacy covers an iron fist.

Since the 19th party congress, China has sent warships and military aircraft into contested areas along its maritime frontier, flying through the South Korean air defence identification zone, sending a submarine into the waters contiguous to the Japanese-claimed Diaoyu or Senkaku islands, circumnavigating Taiwan repeatedly, and unilaterally imposing a new civil air corridor close to the midpoint of the Taiwan Strait. Improvements continue on the artificial islands China constructed in the South China Sea.

Similarly, and taking our story back to India for a moment, China has also strengthened its facilities and capabilities near the India-China-Bhutan border, which is on one of China’s last unsettled land frontiers. Late last summer, Indian and Chinese troops withdrew by prearrangement from a stand-off that started over Chinese road building near the tri-border area, and this facilitated a visit by Prime Minister Narendra Modi to the BRICS summit, with Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa, hosted by Beijing. But since then, China has completed new helicopter landing positions, permanent quarters, road resurfacing and new armour deployments in the area.

Each country in question naturally has the habit of thinking of intrusions by new Chinese capabilities as largely about itself. Japan’s problems might be due to historical memories or Prime Minster Shinzo Abe’s nationalist positions. South Korea may feel pressure because of the deployment there of the THAAD anti-missile systems. Taiwan’s troubles may be due to leadership by a pro-independence political party.

How China’s military is girding for battle, and what it means for neighbours

I would suggest that China’s neighbours start thinking about these new encounters with China’s growing power less individually and more collectively. After all, just over two years ago, Xi ordered a massive restructuring of the armed forces and retired a large portion of the military leadership for a variety of reasons. In the process, Xi has personally interjected to promote a younger and often less-experienced officer corps, and has empowered them with resources and new generations of equipment. In this light, it is hard to imagine that local commanders would not feel pressure to show their stuff across the board.

Back in Beijing, there may be policy mandarins authorising pointed displays of China’s capabilities for a specific purpose here or there, but the general pattern suggests that something larger and of more concern is at work.

The squadron that seemed to be heading for the Maldives was more likely to have been on an annual exercise to the eastern Indian Ocean that was misread by observers as connected to the crisis in Male. In the future, if present trends hold, they are likely to see more such exercises, with larger forces, getting closer to and then beyond the Maldives.

Driven by India into China’s arms, is Nepal the new Sri Lanka?

The historical example of Germany’s 19th-century reunification and industrialisation comes to mind. To simplify, German strength destabilised the Europe that Klemens von Metternich and others had put into equilibrium after the defeat of Napoleon. The US has for decades provided the capacity to counter instability in the Asia-Pacific (or, if you will, the Indo-Pacific). Now, Washington’s hand on the tiller appears far more uncertain and unreliable. China’s neighbours would do well to think more collectively about this prospect.

Douglas H. Paal is vice-president for studies and director of the Asia Programme at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

This article appeared in the South China Morning Post print edition as: Flexing its muscles

Post