Not just ‘containment’: America’s real goal may be to undermine China’s Communist Party

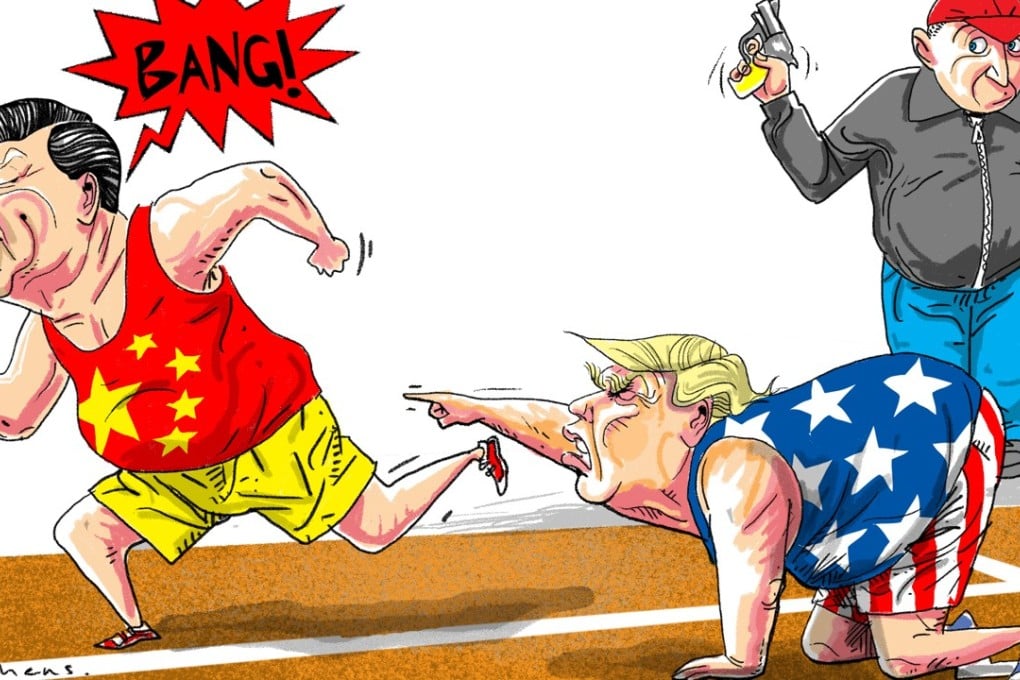

David Zweig questions the wisdom of China’s flashy arrival on the global stage, as it seems to have invited a counter-attack from the US that is looking increasingly like an effort to not just limit China’s growth, but also undercut the party’s legitimacy

In the run-up to the anniversary of China’s reform and opening up this December, commentators have been assessing the country’s foreign policy over these past 40 years, including the Chinese leadership’s decision, circa 2009, to gradually replace Deng Xiaoping’s strategy of “lying low” until China was fully prepared to challenge the US.

Let me elaborate. While China is the trading partner of the world, it remains highly vulnerable to outside pressure. China exports to the US about three times as much as it imports from the US, complicating retaliation by China in a head-on confrontation. China remains deeply dependent on importing American and European technology.