Why Brexit may be the least of the EU’s worries

- Vasilis Trigkas says the blow of the UK leaving the union will be considerable, but it is only an exacerbating factor. In a European parliamentary election year, economic stagnation and a turn towards populist politics are far more worrisome

“The centre cannot hold”, a line from the W.B. Yeats poem, The Second Coming, has become a classic op-ed aphorism in an epoch of ascending demagogy. To extend it beyond domestic politics, the line could be used on the European Union. Indeed, in 2019, the EU may not hold.

If Brexit is successful for Britain, it will set a precedent for other EU members to follow, further undermining the grouping’s cohesion; If chaotic, it will damage the EU’s economy and could provoke a geopolitical clash between Germany and the UK, which could lead to the unravelling of the post-second-world-war intra-European pacifism. This does not mean Panzers and Spitfires; expect instead vitriolic rhetoric, punitive regulations and covert actions culminating in an unprecedented “war by other means”.

To do so, they do not need to win over the majority of voters across Europe; they just need to win enough votes to form the second-largest parliamentary coalition. If they succeed, they will undermine the socialist alliance, the current second-largest coalition, and be able to constrain the agenda of the conservative European People’s Party.

In addition, the political battleground for the appointment of the new commission – the EU’s all-powerful executive body – will be tangled. Even if there is agreement on portfolios and new commissioners by early autumn, the ideological mix of the new commission is likely to erode its effectiveness and further boost Euroscepticism.

This is not where EU problems end, however. The euro, the project that started it all and turned Europe from a sui generis union of postmodern sovereign states with an integrationist dream to militant blocs of creditors and debtors, has become the sword of Damocles hanging over the heads of Eurocrats.

Europe’s economic woes are more troubling than China’s

Eurocrats nonetheless are “resting on their laurels”. They will assuredly refer to the agreement reached last December by EU finance ministers and declare that the euro zone is now stronger than ever before due to significant regulatory reforms. In truth, however, reforms have been slow and the most stabilising reform of all – a common euro zone deposit insurance scheme – remains only a proposition. As political economist Barry Eichengreen puts it, the agreement “falls far short of banking union, fiscal union and political union … It will not change the operation of the monetary union.”

How worried should Asia be about Brexit? Here’s the number to watch

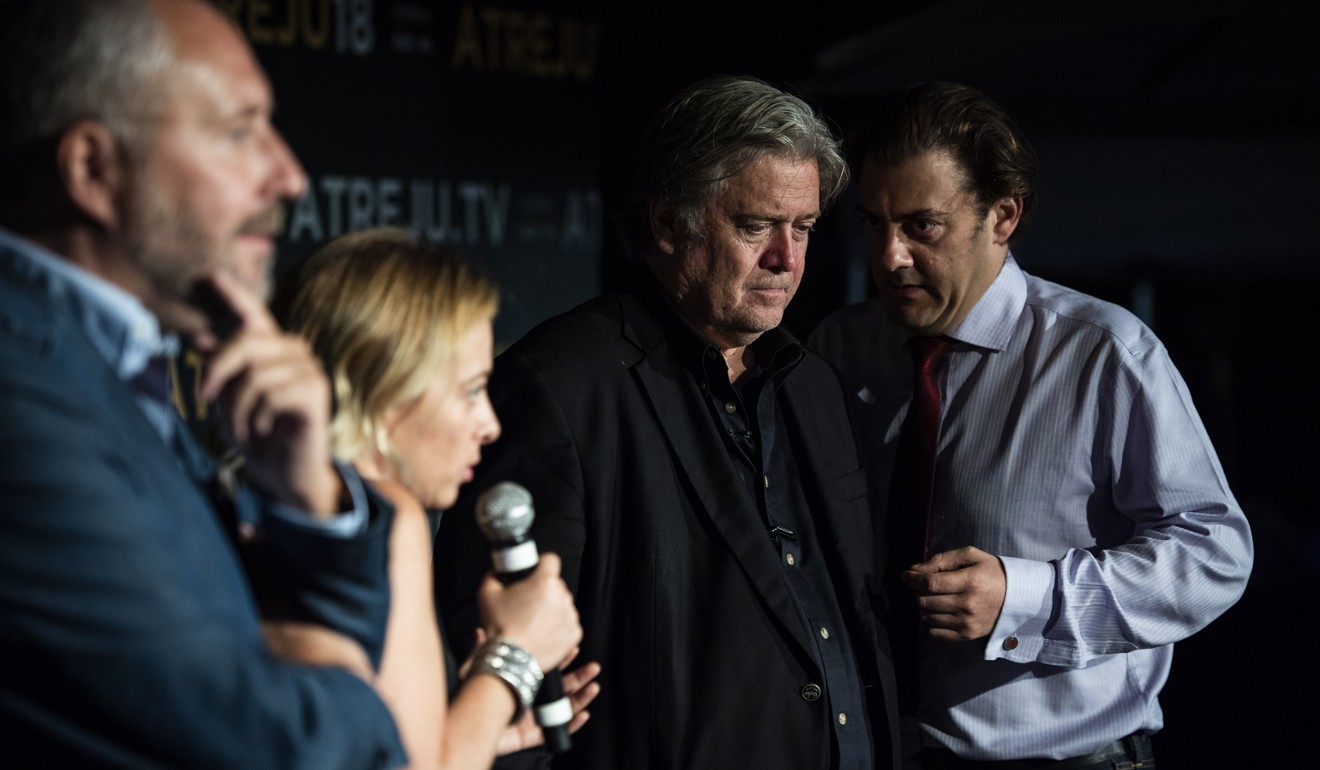

Moreover, a loss of the EU’s global diplomatic leverage would heavily undermine China’s efforts to promote a “multipolar world” to balance out America’s unipolarity. Perhaps this is one of the reasons why Trump’s apostle in Europe Steve Bannon is zealously strategising to weaken the EU.

In Yates’ poem, the centre did not hold. And Europe may now be counting down to an apocalypse triggered by the electoral cycle in May. Salvation will not be found in divine revelation, but only in persuasive deliberation about the cogent benefits of a democratic European federalism for the many and not the few.

Vasilis Trigkas is an Onassis Scholar and research fellow in the Belt and Road Strategy Centre at Tsinghua University