The world economy is headed for a recession. China won’t be there to save it this time

- China’s economic health is important to the world not just because of its importance as a buyer and supplier, but also because of anxieties that it is less well placed to provide the massive stimulus it did after the 2008 financial crash

A decade after the global financial crisis, with the world’s leading economies still addicted to the near-zero interest rates of the emergency response of quantitative easing, it seems the global economy remains on life support, with our experts still flummoxed about how to restore economic health.

Government and corporate debt sits at record levels, with most central banks warning political leaders the monetary armoury is empty. They are calling for fiscal stimulus – like building infrastructure and cutting taxes – when most governments are staring at deep budget deficits and under pressure to cut, rather than increase, spending.

Martin Wolf threw light on this elephant in the room in the Financial Times last month: “The astonishing fact is that the six largest high-income economies, including now even Italy, can borrow for 30 years at a fixed nominal rate of close to 2 per cent, or less … One has to be desperately pessimistic about growth prospects to believe it is impossible to manage substantial borrowings, on such terms.”

In short, our economic leaders are so gloomy about growth prospects for the next three decades that they are unwilling to borrow money even when that borrowing is virtually free. In the words of Harvard economics professor Lawrence Summers: “Governments that run chronic surpluses are failing to do their part to support the global economy and should be the object of international scrutiny.”

How the US and China can find middle ground and get past the trade war

I am sure many of you are feeling that I am being unreasonably gloomy, but the data available to us points with terrible consistency in the direction of recession.

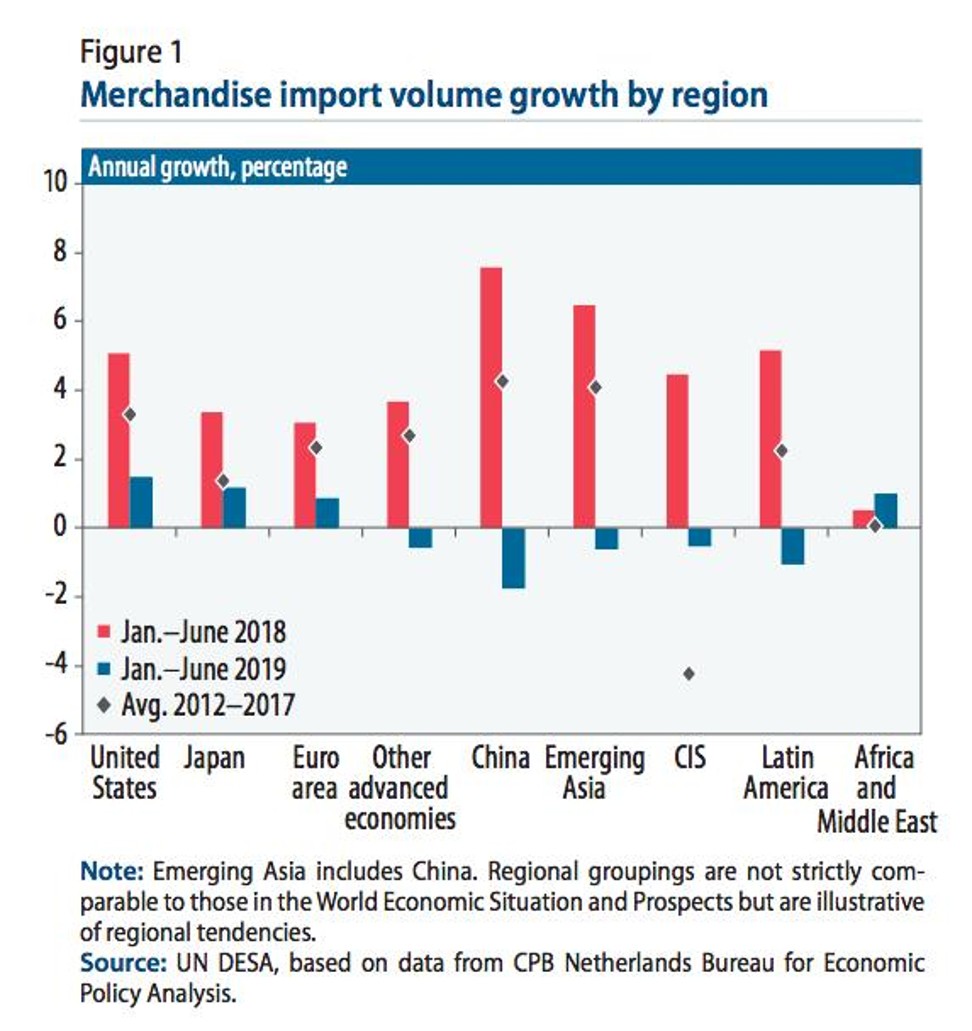

Singapore reported non-oil exports down 8.1 per cent in September – the seventh consecutive monthly fall – with electronics exports down 25 per cent.

The Fed and the ECB can’t save the global economy by themselves

The European Commission reported on Thursday that economic growth in the EU will slow to 1.1 per cent in 2019 – the lowest since the sovereign debt crisis – and forecast that global growth “is set to fall this year to a pace usually associated with the brink of recession”. “As the slowdown spreads, labour markets will lose steam. Wage growth may already have stopped increasing …”

At the heart of Europe’s slowdown is the car sector, particularly in Germany, where growth is expected to slow to 1 per cent from a forecast 1.5 per cent. According to the IMF, global car production in 2018 fell 2.4 per cent. In the US, car production contracted 3.4 per cent in 2018, and a further 2 per cent in the first seven months of 2019, the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs reported; in the EU, production fell by over 10 per cent in the first half of 2019.

China needs to arrest slowing growth, and has the means to do so

China’s 2008-9 stimulus amounted to an estimated 19 per cent of GDP, whereas its measures over the past two years amount to a more modest 7 per cent, according to the FT.

If we are on the brink of a new recession, and even China is not on hand to provide fiscal stimulus, then how dangerously ill-equipped are we? As Summers argued, the danger is not so much a global economic slowdown as the difficulty of doing much in response.

David Dodwell researches and writes about global, regional and Hong Kong challenges from a Hong Kong point of view