Advertisement

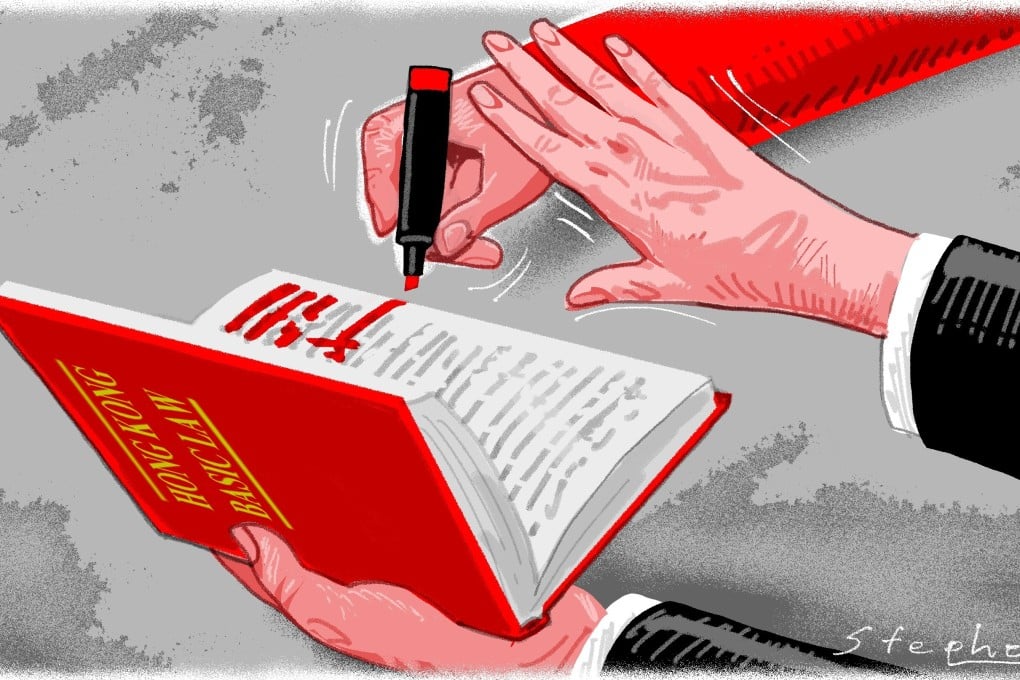

Opinion | Hong Kong’s Basic Law may be conflicting and confusing – but it’s still the best system for relations with China

- For all its flaws, the Basic Law protects Hong Kong’s separate system and can continue to do so beyond 2047, provided work begins now to resolve some of the deep-rooted contradictions. This cannot happen without basic trust

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

0

As Hong Kong battles to contain the coronavirus and the global death toll rises above 80,000, it is not surprising that Saturday’s 30th anniversary of the Basic Law’s promulgation was a subdued affair. Who cares about arcane legal technicalities at a time when the world is facing a life-or-death struggle?

But there is little that happens in Hong Kong which is not underpinned by the city’s de facto constitution. This includes the government’s response to the coronavirus. The powers it uses to impose quarantine, restrict travel and close businesses are subject to the protection of rights and freedoms provided by the Basic Law.

The multibillion-dollar Hong Kong relief measures to help those hit hard by the economic impact highlight the control the law gives to the city over its own finances and taxes.

When Hong Kong finally emerges from this traumatic time of anti-government protests and fight to contain the virus, efforts must focus on rebuilding confidence so the city can move forward. At the heart of Hong Kong’s problems lie issues arising from the Basic Law. But it will not be easy to resolve them.

This unique law has been the subject of fierce disputes since the drafting of it began in the mid-1980s. It provides the legal foundations for the “one country, two systems”, arrangements for when Hong Kong returned to China in 1997.

Advertisement