When the US Federal Reserve announced on last Wednesday that it was “committed to using its full range of tools to support the US economy in this challenging time”, the market read it as the Fed would do whatever it takes to support the United States in its worst pandemic and economic

recession since the 1930s.

Since the beginning of this year, the Fed has expanded its balance sheet by an unprecedented US$3 trillion, to just under US$7 trillion, by buying US Treasuries, mortgage securities and commercial debt. Including the

European Central Bank, Bank of Japan and

People’s Bank of China, the world’s top four central banks have added about US$6 trillion this year to their balance sheets, reaching US$25.2 trillion, or 28.7 per cent of last year’s global gross domestic product. That is serious money – and your money.

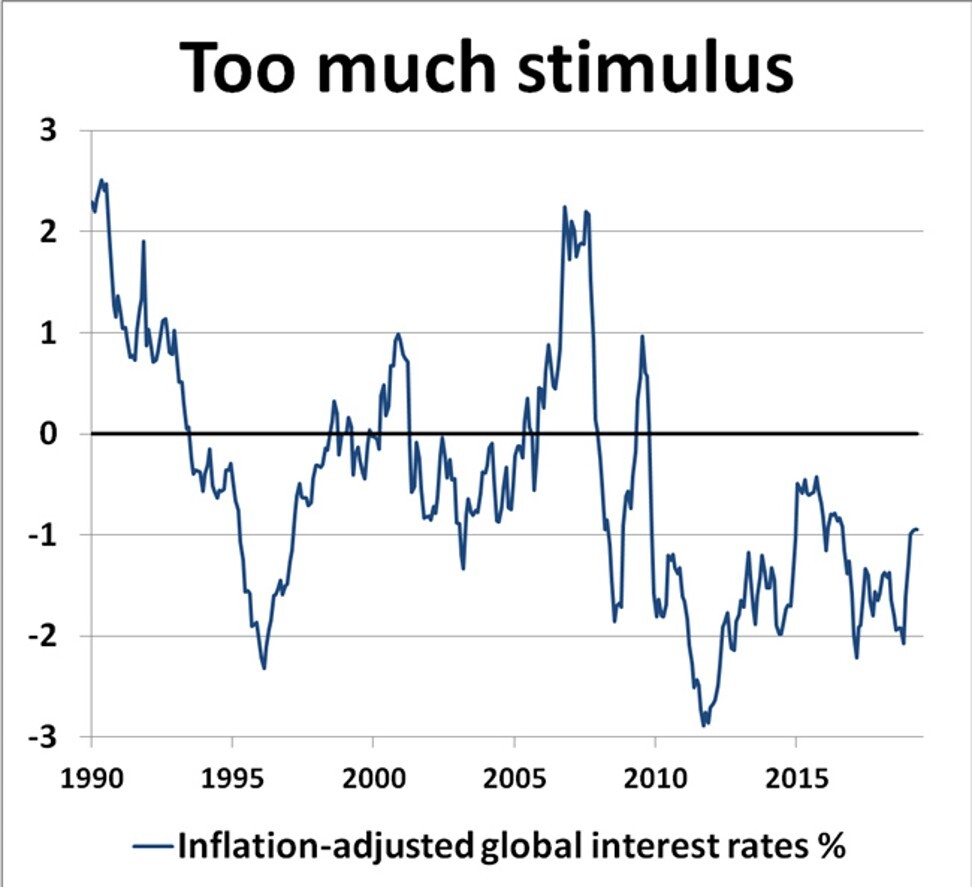

What are the effects of such central bank action? First, inflation remains low because there is much excess capacity due to the coronavirus lockdowns. Second, stock market prices are

near record highs and have mostly recovered from the March dip because of excessive market liquidity. Third, interest rates are near zero or negative, which removes their pricing or resource allocation role. Interest rates are kept low when the central bank is willing to supply liquidity to keep it so.

Central banks are now the largest buyers of government debt and commercial and mortgage paper – becoming not a lender of last resort but a major player in the market. Because central banks will do whatever it takes, investors no longer look at interest rate signals to decide what to buy, and instead follow what central banks do.

In the 1990s, the market began to follow the Fed’s rate announcements, with investors expecting interest rate cuts to stop the market wobbling. More signalling than serious action, hints of rate cuts were enough to steady nerves. But when medicine is overused, ever-larger doses are needed and have less effect, until everything goes downhill.

In the 2008 global financial crisis, the Fed and European Central Bank borrowed the idea of

quantitative easing from the Bank of Japan, the first to bring interest rates to near zero and use its balance sheet to create easy money conditions to help Japan recover from deflation.

Between 2001 and 2020, the Bank of Japan’s balance sheet expanded from 20 per cent of GDP to over 107 per cent; whereas the Fed’s grew from 6 per cent of GDP in 2005 to just under 20 per cent. Pure coincidence perhaps, but

gold prices have risen by 28.9 per cent this year, against 28.8 per cent for the assets of the big four central banks to June. The rise in gold prices is an indicator that people are losing trust in central bank money.

Global governments have committed to US$11 trillion of fiscal measures to tackle the pandemic crisis, with advanced economies running fiscal deficits at around 16.5 per cent of GDP on average, and total debt expected to touch 130 per cent, the highest since wartime financing. Such deficits and debts are only possible because central banks fund half of the fiscal spending. Without that, interest rates would be higher and governments would be in dire straits.

Rescuing the economy exacts a cost. A study of 12 advanced economies from 1920 to 2015 showed that expansionary monetary policies increased the income and wealth share of the

top 1 per cent of the population by roughly between 1 and 6 percentage points.

In effect, loose monetary policy rewards borrowers and punishes savers, worsening social inequality. Global interest-bearing deposits are roughly US$60 trillion and held mostly by the low and middle classes. A rate cut of 1 per cent would reduce their annual deposit income by US$600 billion and subsidise borrowers.

Recent action by central banks and financial regulators to

cap or stop bank dividends to preserve capital buffers is a classic example of nannying, weakening the free market’s ability to respond to risks. Retail and institutional investors like bank shares because they are leveraged diversification plays on the real economy. Bank stocks are blue chips that pay steady dividends.

In troubled times, good banks survive and do better on recovery. But if their dividend payouts are restricted, retail investors are forced to enter the stock market and punt. In other words, if you remove the safe haven role of banks, prudent investors are fed to a world where they become speculators in a

bubbly market created by excessively low interest rates.

If the bank does not want to pay cash, let them pay out in stock; if they feel their capital is insufficient, let them raise more in the market. But by capping dividends, financial regulators are signalling that they know better. That is not a vote of confidence in the banks or the quality of bank supervision.

Central bankers have become nannies who preach of a free market but do not trust it. By often rescuing the market, and by growing so large themselves, they are becoming the market while insisting that the so-called market should bear the ultimate risks. In effect, they are bailing out the smart money and passing the losses to the gullible, who still believe central bankers understand what they are doing.

No wonder the financial world is in deep trouble.

Andrew Sheng is a former central banker and financial regulator. The views expressed here are entirely his own