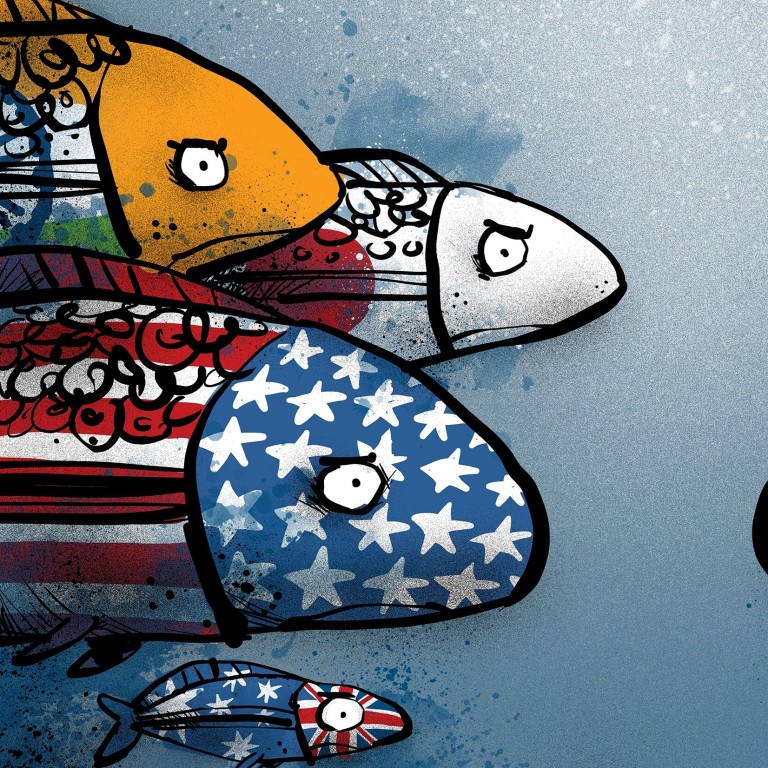

South China Sea: ‘alliance of democracies’ ready to counter Beijing aggression

- Recent statements signal that the US, Australia and other countries will not back away from the right to freely navigate disputed waters

- It is clear China’s assertiveness towards its neighbours is not only destabilising to the region but also becoming a global security concern

These actions not only challenge China’s claims, they are escalatory measures to signal that the United States, Australia and other countries will not back away from the right to freely navigate the South China Sea.

02:32

Washington’s hardened position on Beijing’s claims in South China Sea heightens US-China tensions

First, it is true that access to resources is part of the competing claims in the South China Sea. According to the Centre for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, the South China Sea accounted for 12 per cent of the fish caught globally in 2015. More than 50 per cent of fishing vessels in the world are believed to operate in the sea.

Second, China’s aggressive claims over the South China Sea would allow it to virtually seal off the body of water by interdicting strategic resources coming through the Malacca Strait. Chinese sovereignty over the sea would allow Beijing to exercise coercive diplomacy by controlling strategic resource flows with every country in the region.

With military assets already in place in the Spratly and Paracel Islands, Chinese sovereignty over the South China Sea would allow its military to establish tactical and operational control as well as unopposed freedom in its approaches to Taiwan.

02:19

Taiwan military drill simulates coastal attack amid rising tensions with mainland China

Additionally, it would enable China to address some unfinished business with Japan from its colonial era. As far back as 1951, the US Central Intelligence Agency concluded in a now-declassified report that Taiwan was “the last stronghold of the Nationalist regime” and that the Chinese were resolute in “capturing Taiwan in order to complete the conquest of Chinese territory”.

Significantly, India recently held a major exercise off the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal – the entry point into the critical Malacca Strait. New Delhi is also looking into expediting the reinforcement of military forces in the Andaman and Nicobar Command.

As the Quad – the US-led military grouping with Australia, India and Japan – begins its trilateral exercise in the Philippine Sea and the Indian Ocean, Australia is poised to join the Malabar exercise and other Western naval forces making their presence known in the region.

The message is clear: China’s assertiveness towards its neighbours is not only destabilising for the region but is also becoming a global security concern.

03:23

The South China Sea dispute explained

As the People’s Republic of China approaches its centennial in 2049, President Xi Jinping is a man in a hurry. Part and parcel of this will mean the unification of Greater China and, implicitly, unopposed control of the South China Sea.

However, China should measure its historical grievances and ideological priorities against the costs. It cannot have the contradictory desires of peace on the one hand and retribution on the other. The world was forced to live through two devastating wars in the 20th century, and there is little interest in doing it again.

Patrick Mendis, a former American diplomat and military professor, is a Taiwan fellow of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of China and a distinguished visiting professor of global affairs at the National Chengchi University. Joey Wang is a defence analyst in the United States. The views expressed in this analysis are the authors’ own