Advertisement

Opinion | How China’s rise in the Middle East can inform US policy under Biden

- China has courted the Middle East with offers of investment and technology, issues at the very heart of the superpower competition with the US

- However, Beijing is wary of the region’s instability, and remains sensitive to American power and influence, which Biden might seek to reassert

Reading Time:3 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

3

China is cementing its position in the US sandpit. As the Biden administration re-evaluates US foreign policy, and its China policy in particular, one region that demands a closer look is the Middle East. Traditionally a US domain, the region is undergoing an unprecedented transition and could become the next front in the superpower competition.

Propelled by its ballooning demand for energy, China sensed an opportunity in the Middle East and began showing its appetite for what it initially saw as a remote, complicated region under the US sphere of influence. After the Arab spring and against the backdrop of a shrinking US presence and anger at US mishaps, China moved swiftly to stake its claim.

China’s approach to the Middle East has changed dramatically over the past decade. Nearly half of China’s oil and natural gas now comes from the Middle East, and increasingly, Chinese goods, services and technology are finding their way into homes, hearts and minds in the region.

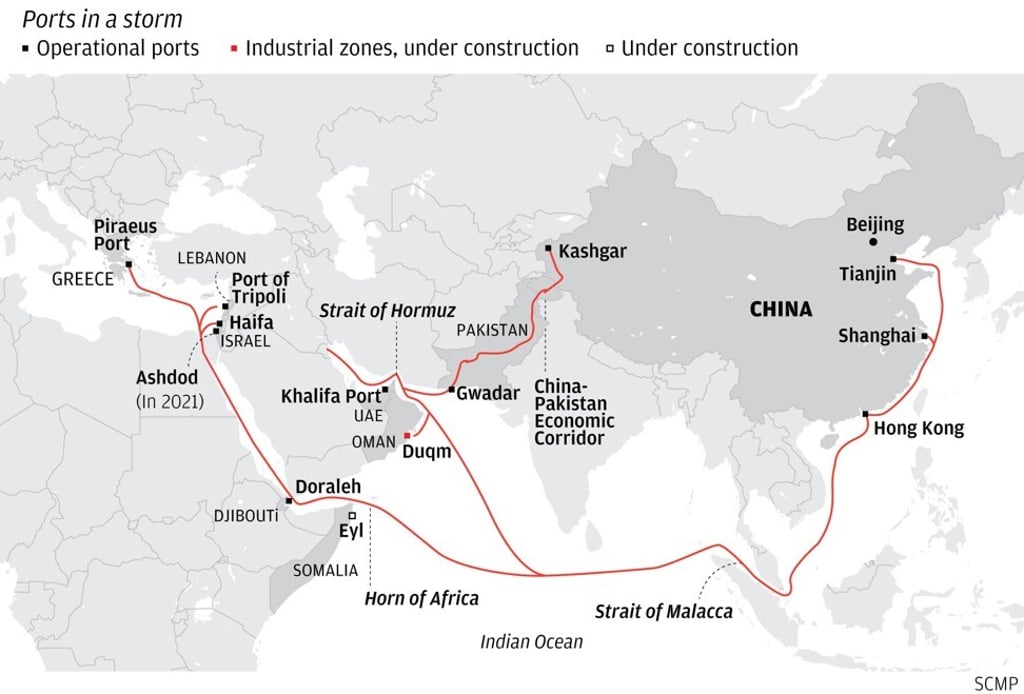

As the largest investor in the region, China completed its first overseas military base in Djibouti in 2017, extending its reach to the Strait of Hormuz, a crucial maritime crossing.

Beijing is also heavily involved in infrastructure projects with vital US allies including Israel. Chinese investment in Israeli technology and growing involvement in Israeli infrastructure projects, including the Haifa and Ashdod ports, have raised US concerns.

Advertisement