European climate change law: consensus politics is powering the EU towards net zero, but will others follow?

- The European Climate Law requiring binding action from EU institutions and member states to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2050 is the result of years of negotiation and dialogue

- Most importantly, it rests on the recognition of a shared vision to slow climate change. Other major economies should commit to this transition in their own interests

Net zero or climate neutrality means remaining emissions are balanced out by the removal of greenhouse gases from the atmosphere into “carbon sinks”, such as forests.

The law creates a five-yearly process for reviewing progress towards climate neutrality. It subjects any draft laws or budgetary proposals to a test of consistency with the net zero objective.

It strengthens the EU’s 2030 emission reduction target to 55 per cent compared to 1990 levels and requires a review of EU laws to make them consistent with this goal.

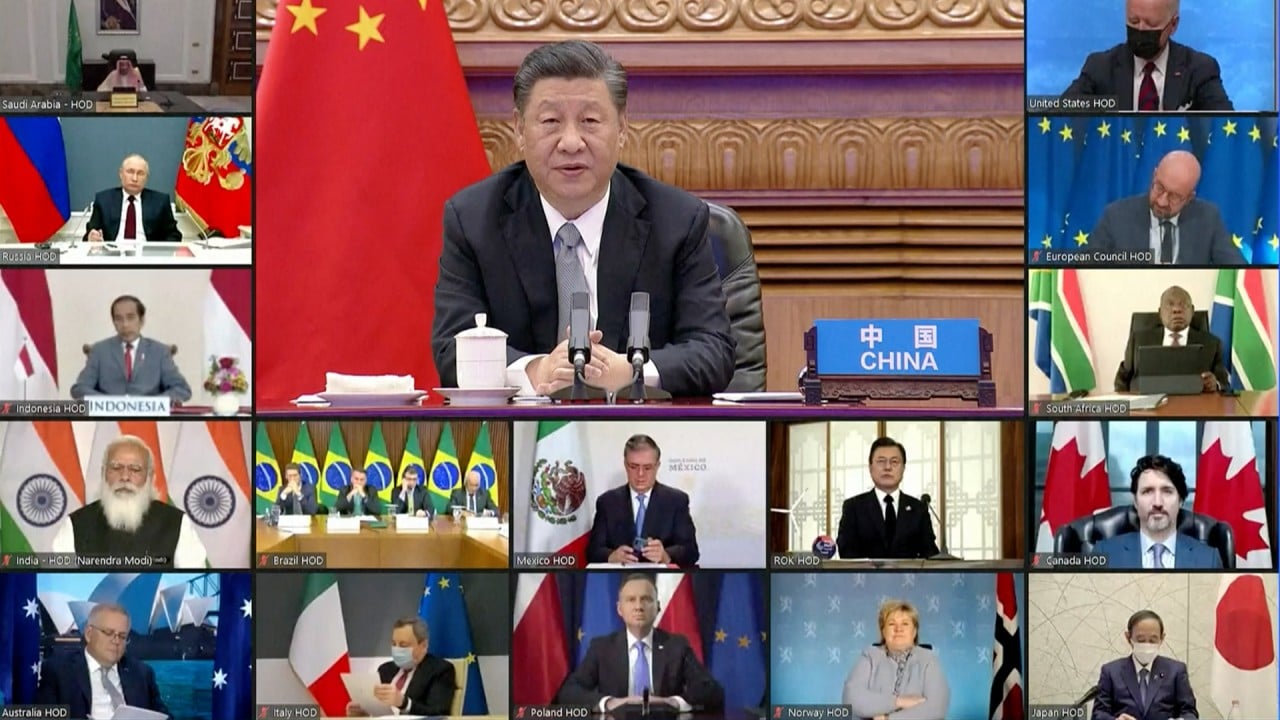

In short, the climate law puts the EU – one of the three largest economies in the world alongside the US and China – on a legally binding pathway to net zero by 2050.

For other countries, and particularly for fellow democracies, the way that the law was adopted should be just as noteworthy as what it contains. The climate law was approved in parliament with the support of conservatives, social democrats and liberals.

The support of the three largest EU political groupings, which regularly compete for office in national elections as well as for seats in the European Parliament, is a powerful example of the broad-based political consensus needed for major and enduring reforms.

This consensus was built through years of negotiation and dialogue between the political parties and between 27 member states with very different economies, per capita incomes and energy mixes.

Clearly, the political parties each have their own particular priorities and some member states have been much more forward-leaning on this agenda than others. However, the continual work of maintaining and extending a shared vision on climate has created conditions of stability for investment and provided a strong signal to the market.

Today, the EU has the world’s deepest capital markets in sustainable finance and a progressively strengthened carbon pricing regime. It has also demonstrated that economic growth can be decoupled from emissions on a durable basis.

The goal is to pursue net zero in a socially cohesive manner, while creating new economic opportunities in the communities most affected by change.

Of course, it would be pointless to cut emissions in the EU only to have polluting activities migrate offshore. Or for European companies making the effort to cut emissions to be undercut by competitors with no such obligations.

That’s why the European Commission will soon be proposing a carbon border adjustment mechanism, to create a level playing field on the cost of emissions.

Time to make carbon polluters pay, not just talk emissions cuts

Every country has its own political system and culture. It would be wrong to suggest that the process in the EU could or should be copied elsewhere.

Nevertheless, the European Climate Law points to the value of negotiation and consensus. With goodwill and a proper awareness of the stakes, political competitors can hammer out an agreement on truly existential issues.

While some continue to deny the need for net zero, the net zero economy that the world needs is already under construction. All major economies should commit to this transition in their own interests.

Dr Stephen Minas is associate professor at the Peking University School of Transnational Law and has worked on several EU climate processes. This article is written in a personal capacity