Sports diplomacy: China should try a new tack for the Belt and Road Initiative

- Ping-pong diplomacy paid off for China, more than ‘wolf warrior’ diplomacy has

- If the belt and road plan could help bridge the sporting infrastructure gap in countries, it would improve local sentiment and strengthen economic cooperation

The Belt and Road Initiative has inevitably become a matter of controversy in the West, amid tales of corruption and allegations of debt traps. While not all the blame can be laid at China’s door, it may have still lost some public support among the belt and road nations.

As for the Belt and Road Initiative, there is one aspect that most will agree can be improved: its accessibility for the youth who will one day govern their countries. One of the best ways to improve it? Sport.

In countries where governments have other priorities, the lack of sporting infrastructure could seriously undermine young people’s potential. When sports games are played by the privileged few, the potential of talented but underprivileged youth is ignored.

Why G7 leaders’ rival plan to China’s Belt and Road Initiative is wrong-headed

Many traditional sports and games in belt and road nations have the potential to be scaled up internationally: baok chambab (Khmer wrestling) from Cambodia and sepak takraw (kick volleyball) from Malaysia, to name but two.

Traditional sports and games can be the backbone of communities in belt and road countries, and supporting them is consistent with Beijing’s vision for “a community of common destiny for all mankind”.

Traditional sports and games are intangible parts of cultural heritage that need to be protected and promoted to foster community spirit, bring young people together, and instil a sense of pride in society’s culture.

More than 40 per cent of the world’s 7,000 languages are at risk of disappearing – and who knows how many traditional sports and games are in danger of extinction?

Why Western narrative of China’s ‘debt trap diplomacy’ is another big lie

Closing the sporting infrastructure gap in the countries along the belt and road’s trade routes could boost not only cultural preservation, but also cultural exchange between young Chinese and non-Chinese.

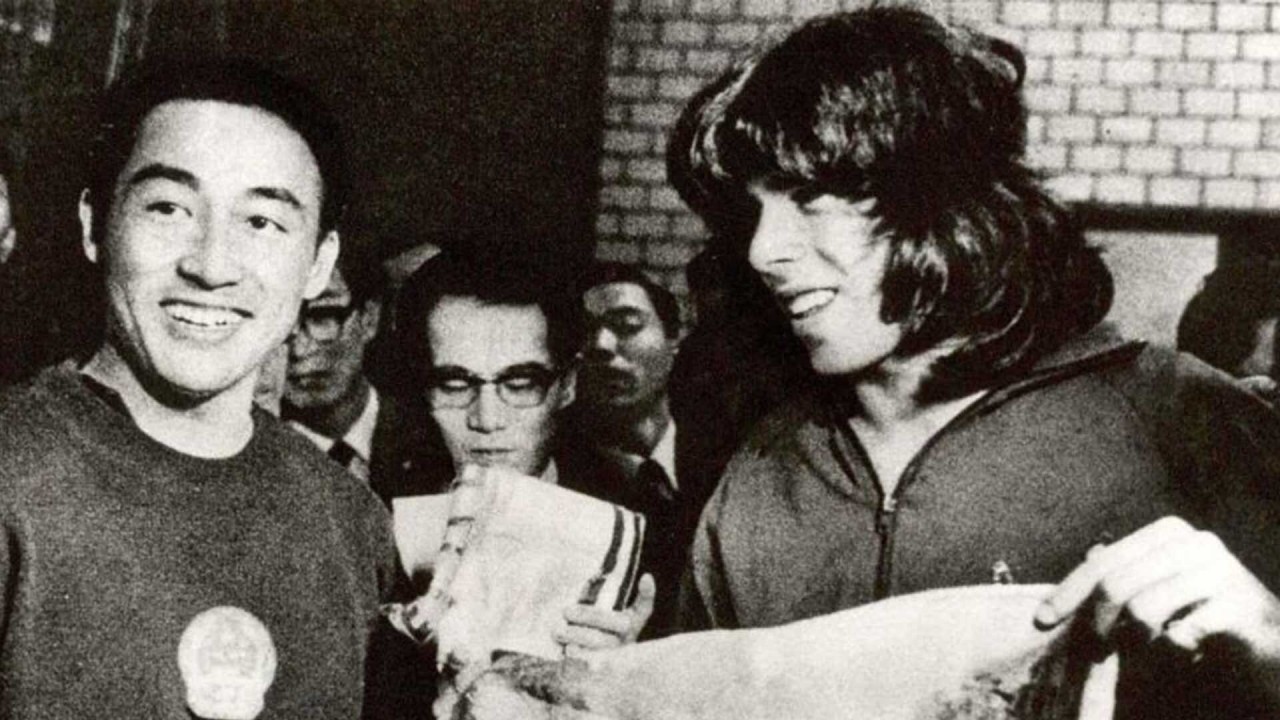

Humanising the Belt and Road Initiative, moving away from the usual government-to-government approach and focusing more on people-to-people interaction: this should be a matter of when, not if, for Beijing. The United States has long understood this; the State Department has a Sports Diplomacy Division. What is Beijing’s answer to that?

Among the belt and road nations, the participation of ordinary citizens, corporations and governments is needed to support sports infrastructure and foster young people’s sporting development.

When China actively supports meaningful projects to preserve, for instance, traditional sports and games in Indonesia, there is no doubt that the local youth who benefit from the projects will feel more connected to the Belt and Road Initiative. Similarly, many politicians love talking about sports to better connect with ordinary people.

Some criticism of China’s infrastructure investment programme have focused on the low relatability of mega projects and the low engagement with locals, including young people who could tap opportunities arising from the projects. These issues won’t fade away.

Only a Belt and Road Initiative with a stronger social focus can improve local sentiment and strengthen economic cooperation on the ground.

The belt and road can stand the test of time and win over naysayers when it is perceived to be a programme that helps youth, better connects people and promotes cultural interaction. And what could be a more apolitical and popular platform than sport?

Chee Yik-wai is a Malaysia-based intercultural specialist and the co-founder of Crowdsukan, focusing on sport diplomacy for peace and development