Advertisement

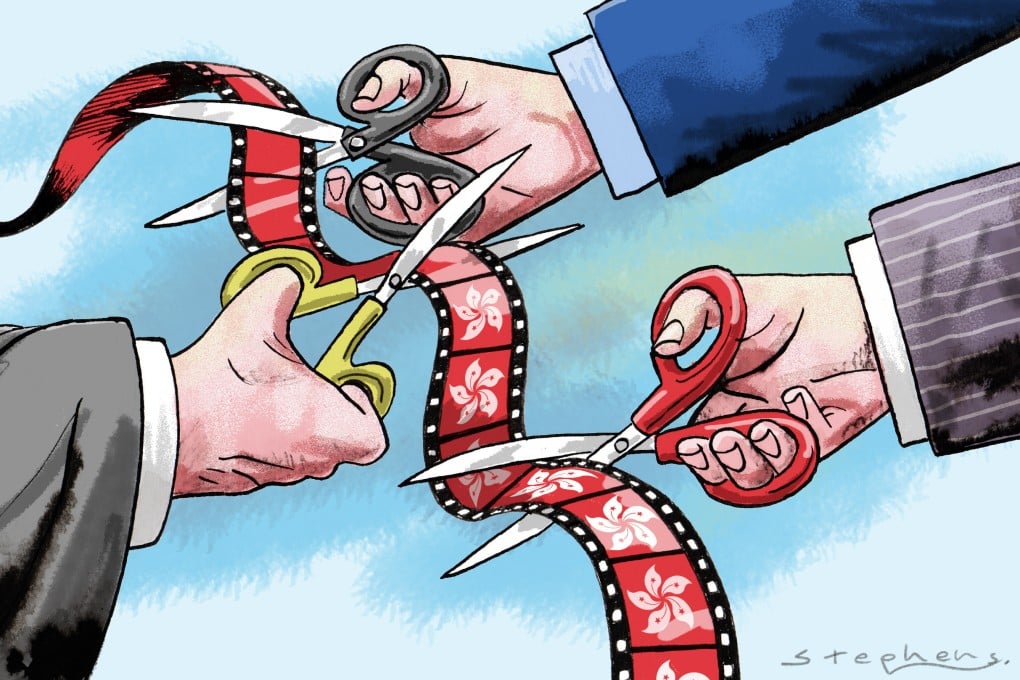

Opinion | How the national security law is hastening the demise of Hong Kong cinema

- The industry’s long-term viability is being challenged amid new censorship guidelines, worries that expressions of local identity can be seen as unpatriotic, and a dearth of actors, who now face increased pressure to prove their patriotism

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

3

Following the 1997 handover, Hong Kong filmmakers censored their work to secure funding and mainland Chinese distribution, but independent films for the local market were still free to broach politically sensitive subjects.

Not any more. The national security law and newly revised film censorship guidelines have ended that creative freedom. There will be no more films like Ten Years, the controversial anthology named best movie at the 2016 Hong Kong Film Awards, that told five dystopian stories set 10 years in the future.

The Hong Kong government, though, is trying to spin a different story.

Secretary for Commerce and Economic Development Edward Yau Tang-wah told a local radio programme last month that “the freedoms we treasure, like the freedoms of speech and creation, are protected” under the national security law and the Basic Law.

Filmmakers ordered to cut scenes under the new guidelines would beg to differ. Yau said only one of the 400 films submitted for approval was banned, but the more pertinent question is how many were ordered to cut scenes.

Far From Home, which was shortlisted for the 15th Fresh Wave International Short Film Festival, was pulled from screening in Hong Kong pending 14 cuts that were ordered. In the story, set during the anti-extradition protests of 2019, the girlfriend of an arrested student protester has an awkward meeting with his parents when she goes to retrieve potentially incriminating items.

Advertisement