Why France is the dark-horse competitor to the US in Asia

- Under Emmanuel Macron, France has championed an independent European foreign policy and expanded its footprint as an arms supplier

- As the US frames its geopolitical battles in ideological terms, France could provide Asia’s illiberal democracies, such as India, Indonesia and the Philippines, with a less difficult alternative

“In the area of defence, our aim needs to be ensuring Europe’s autonomous operating capabilities, in complement to Nato,” Macron said, as he proposed a joint European defence force.

Unlike the US and others, only 8 per cent of France’s goods trade passes through the South China Sea. That fact has given Macron the luxury of taking a more sympathetic view of Beijing, even in the face of increased Chinese aggression in the region.

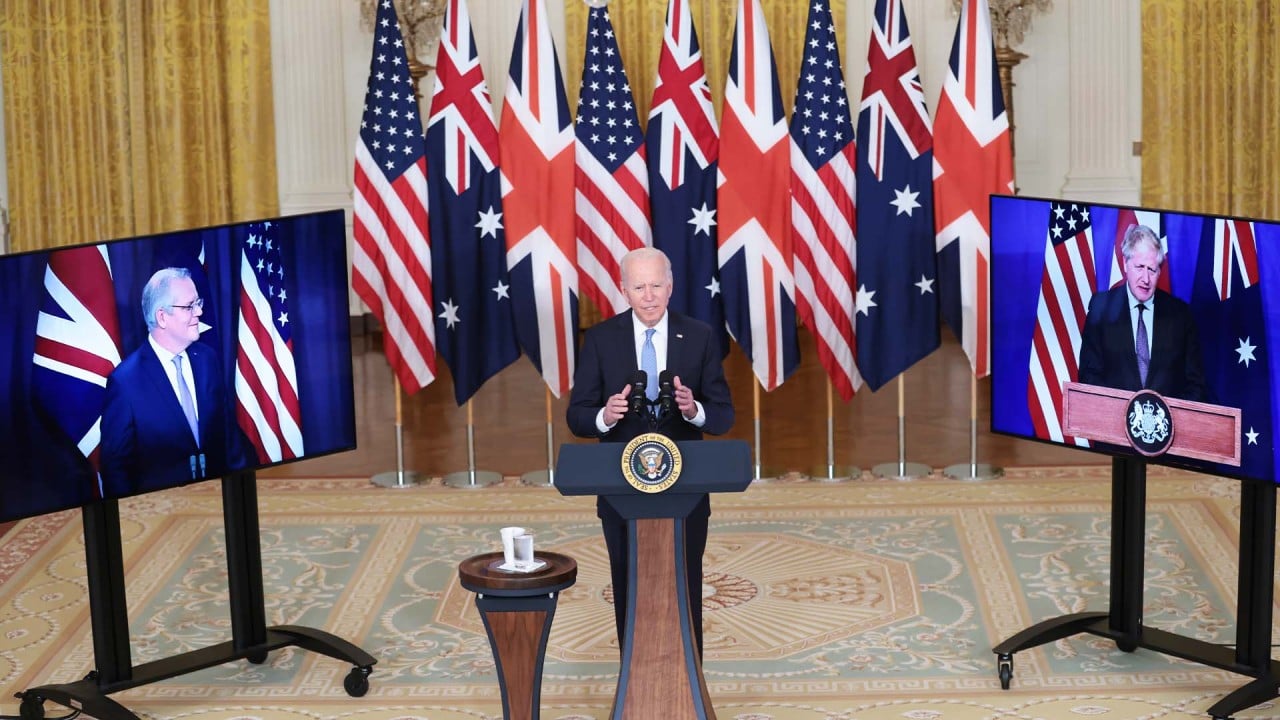

In its aftermath, Macron told Australia’s Prime Minister Scott Morrison that the deal had broken their “relationship of trust”. Biden later attempted to salvage the situation by publicly admitting that the US had been “clumsy” in its approach.

Why many Indians support New Delhi’s neutral stance on Russia

But in the past few years, India has been rapidly reducing arms imports from Russia. Between 2012 and 2016, as much as 69 per cent of its arms imports came from Russia, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Between 2017 and 2021, that figure came down sharply, to 46 per cent.

The problem for Washington, however, is that New Delhi is replacing Russia with France, not the US. In 2021, around 48 per cent of India’s arms imports were from France. Russia accounted for just over 31 per cent. The US cornered under 10 per cent.

These trends have sent ripples through the global arms market: between 2017 and 2021, France exported 59 per cent more arms than between 2012 and 2016. The US only recorded a growth of 14 per cent.

Some of France’s advantage is also political. As the Biden administration increasingly frames its geopolitical battles in ideological terms – pitting democracies against autocracies – France could well gain by providing Asia’s many illiberal democracies, such as India, Indonesia and the Philippines, with a less difficult alternative to the US.

When asked about world leaders who she admires during an interview last month, Le Pen named three right-wing nationalists: India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Britain’s Prime Minister Boris Johnson and Putin.

She has also publicly opposed imposing sanctions in response to human rights abuses, including on China. “I do not believe in threats, I do not believe in moral lessons,” Le Pen said in an interview last year.

In the wake of Trump’s disruptive foreign policy, one of Biden’s key challenges was to find renewed common ground with US allies. Biden chose to do that by making a case for moral and ideological leadership and establishing American primacy in the Indo-Pacific. On all these counts, France has proven to be a tough partner.

Mohamed Zeeshan is a foreign affairs columnist and author of Flying Blind: India’s Quest for Global Leadership