US Federal Reserve’s attempt to turn inflation tide leaves Asian economies exposed

- Comparisons between circumstances today and the run-up to the Asian financial crisis of 1997 should not be overemphasised

- However, a combination of aggressive Fed tightening, a potentially even stronger dollar and pronounced yen weakness could prove problematic for those carrying US dollar-denominated debt

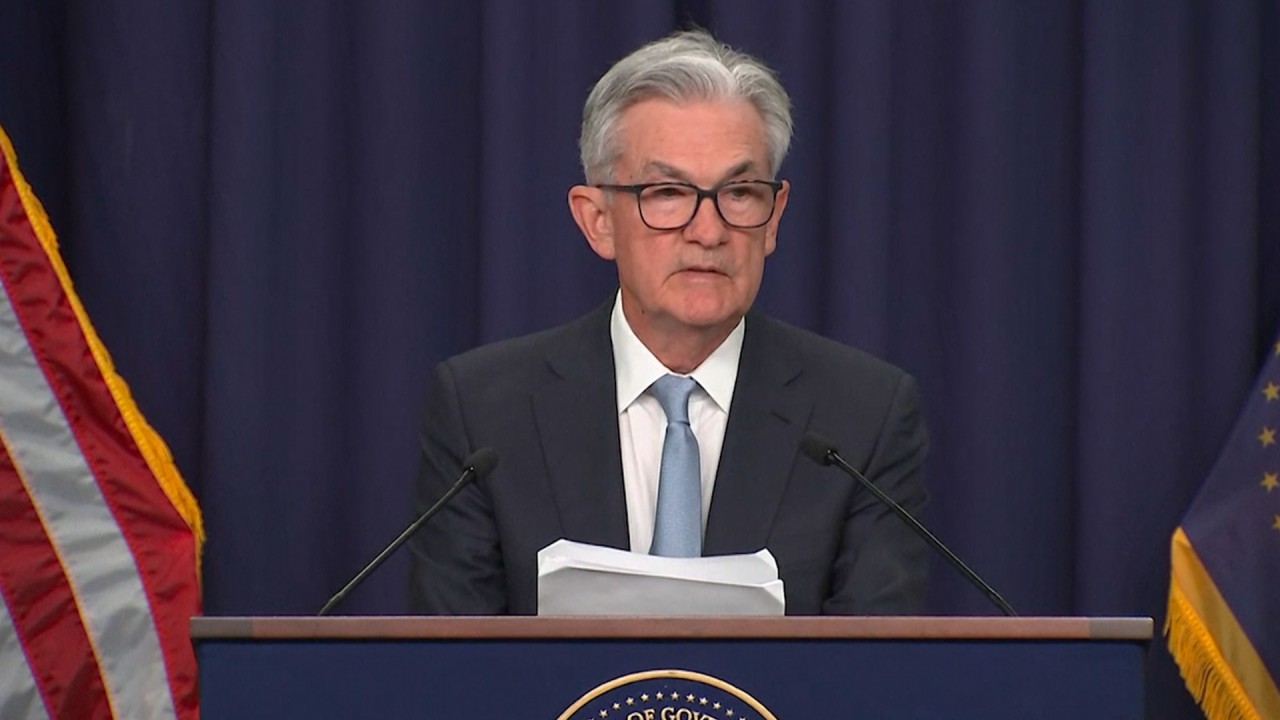

The Fed prepared the ground well for its biggest single rate hike since 1994. Until just days before the announcement on June 15, markets had anticipated a rise of 50 basis points, but after some deft communication from the US central bank, markets recalibrated towards the idea that a 0.75 percentage-point increase was coming.

But what’s also critical is that rate-setters now expect the benchmark Fed funds rate to be substantially higher at the end of 2022 than they had envisaged in March.

June’s projected median policy path now foresees the rate at 3.4 per cent at the end of the year, significantly higher than March’s 1.9 per cent prediction. That means there will be a succession of US interest rate rises this year, with the Fed meeting again on July 26-27.

At the same time, the Fed downgraded its expectation for US gross domestic product growth in 2022 to 1.7 per cent from March’s 2.8 per cent projection. The Fed is now prioritising driving down inflation and is prepared to tolerate a slower pace of GDP growth as a consequence.

While there is always the possibility that American demand for Chinese goods could be adversely affected by the combination of existing US inflationary pressures and tighter Fed monetary policy, China’s economic heft provides quite a cushion.

Other central banks, such as the Swiss National Bank, are also in hiking mode but not the Bank of Japan. The Japanese central bank seems determined to use the recent uptick in global inflationary pressures, also evident in Japan, to eradicate a long-established and deep-rooted deflationary mindset.

Friday saw the Bank of Japan recommit to its yield curve control policy of keeping the yield on the benchmark 10-year Japanese government bond close to zero, reiterating its determination to purchase an unlimited amount of 10-year Japanese government bonds at 0.25 per cent in pursuance of that objective.

How Japan’s foray into a digital yen could be its key to Web 3.0 universe

That leaves a lot of other Asian countries in a quandary. Even as the Bank of Japan persists with yield curve control, with inflation in South Korea at a 13-year high, the Bank of Korea raised interest rates to 1.75 per cent last month and emphasised that its “policy focus will be on price stability for some time”.

But, if the Bank of Japan does stick with yield curve control and the Bank of Korea tightens monetary policy further, this could also translate into a yet stronger Korean won versus the yen, a prospect that would not play well with South Korean exporters that vie for business globally with competitors in Japan.

Additionally, while comparisons between circumstances today and the run-up to the Asian financial crisis of 1997 should not be overemphasised, no one should underestimate the risk that a combination of aggressive Fed tightening, a potentially even stronger dollar and pronounced yen weakness could prove problematic for those carrying US dollar-denominated debt who then find they lack the wherewithal to service it.

With the Fed determined to turn the tide of US inflation, billionaire investor Warren Buffett’s famous quote bears repeating: “Only when the tide goes out do you discover who has been swimming naked.” The world may be about to find out who has been skinny-dipping.

Neal Kimberley is a commentator on macroeconomics and financial markets