Opinion | Lack of global consensus bodes ill for health of world’s oceans

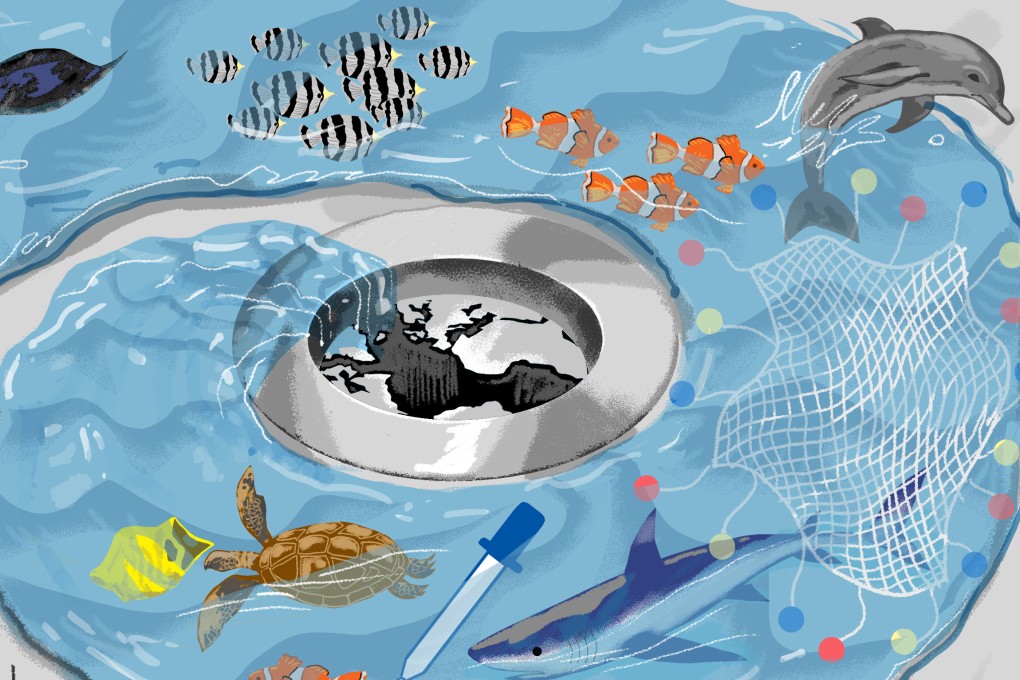

- From marine pollution and harmful fishing practices to biodiversity loss and increasing acidification, our oceans are in trouble but long-term issues tend to get short shrift from political leaders

- The inability to effectively regulate oceans stems mainly from contradictions, anomalies and the realpolitik surrounding the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea

The past 300 years have witnessed rapid technological progress, resulting in the ruthless exploitation of natural resources. Rampant environmental pollution has damaged the health of the planet.

The Lisbon conference brought together some 6,500 participants, including heads of government and high-level representatives. It concluded with a declaration titled “Our Ocean, Our Future, Our Responsibility”, which focused on life below water – the UN’s 14th Sustainable Development Goal.

It exhorted the global community to save the oceans from existing and future threats, including marine pollution, harmful fishing practices, biodiversity loss and acidification. Regretting the collective failure to achieve the development goals, the declaration added: “As leaders and representatives of our governments, we are determined to act decisively and urgently to improve the health, productivity, sustainable use and resilience of the ocean and its ecosystems.”

The health of the world’s oceans has received periodic attention from global leaders but with modest results. For example, the joint communique issued after the 2018 Commonwealth heads of government meeting in London had the theme of “Towards a common future”.