US seeks to bolster tech prowess with return to state-led industrial policy

- Washington is taking a leaf out of Beijing’s book by pouring state funds into technology development, with a focus on semiconductors

- Yet, while both the US and mainland China are striving for greater self-reliance, catching up with Taiwan in advanced chip-making remains a challenge

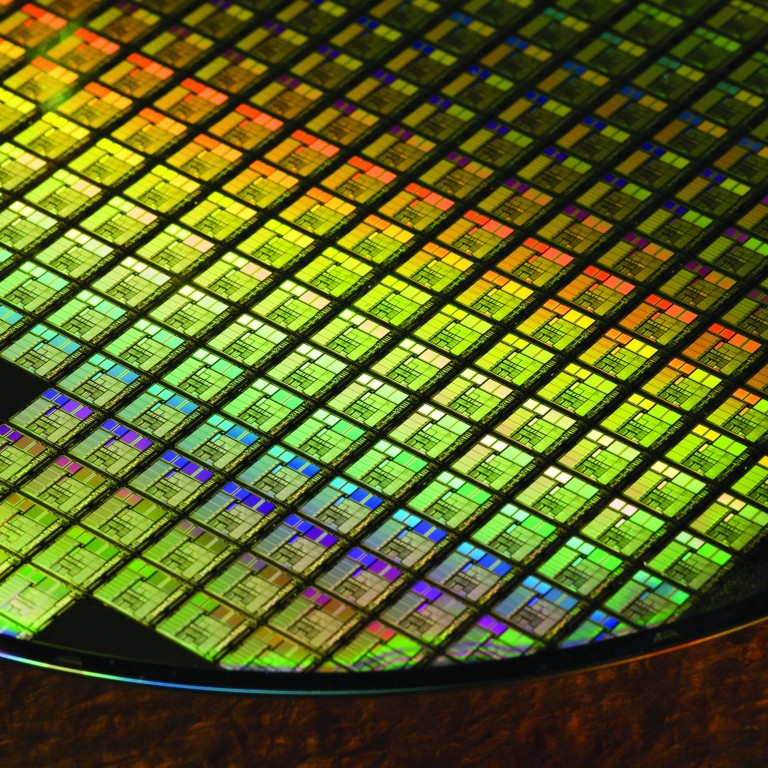

Since the end of the Cold War, though, the imperative for government-led industrial policy in the US has waned, leading to underinvestment in domestic manufacturing and leaving other nations with lower labour costs room to build massive economies of scale. As such, while the semiconductor industry was born in the US, 80 per cent of foundries (or “fabs” in industry parlance) are now located in Asia.

Still, Beijing is putting its money where its mouth is: in 2020, the State Council announced that corporate taxes for advanced fabs would be waived for 10 years, and that the government would offer insurance to fabs for their suppliers.

It is important to point out that there are essentially two types of semiconductor chips: “leading edge” digital chips used for more sophisticated applications such as computers and mobile phones, and “trailing edge” or “mature” analog chips used for less-demanding applications such as cars and washing machines.

Wrestling away Taiwan’s chip manufacturing dominance will not be easy. It takes over two years to start a fabrication plant. Building up the intellectual capital and industrial capacity will take significantly more investment and time.

On the other hand, taking on Taiwan in the “leading edge” chips race may not be necessary for the mainland. Expanding demand for mature analog chips could allow mainland fabs to focus their efforts on building massive scale in this market segment.

As the US returns to an era of government support for industrial advancement, healthy global competition is likely to create winners across market segments, diversifying production and leaving the industry much less concentrated than it is today.

US happy to shoot itself in the foot in tech war with China

With more fabs able to produce a wider range of both leading and mature chips, consumers can look forward to increasingly powerful and efficient phones and PCs, while no longer having to wait months for a new car.

Modern industrial strategies are complex, requiring extensive state involvement in the form of research and development subsidies and infrastructure programmes, as part of a carefully structured long-term plan. The geopolitical chip war is shaping up to be one worth watching closely.

David Chao is Invesco’s global market strategist for Asia-Pacific