Asian central banks are locked in a losing chess match with the US Federal Reserve

- Asian central banks facing currency weakness are stuck with no good moves as the Fed presses forward with interest rate increases and quantitative tightening

- Short of a dramatic reversal of the market’s current bullish view of the US dollar’s prospects, China’s central bank might be limited to managing the rate of descent of the yuan versus the US currency

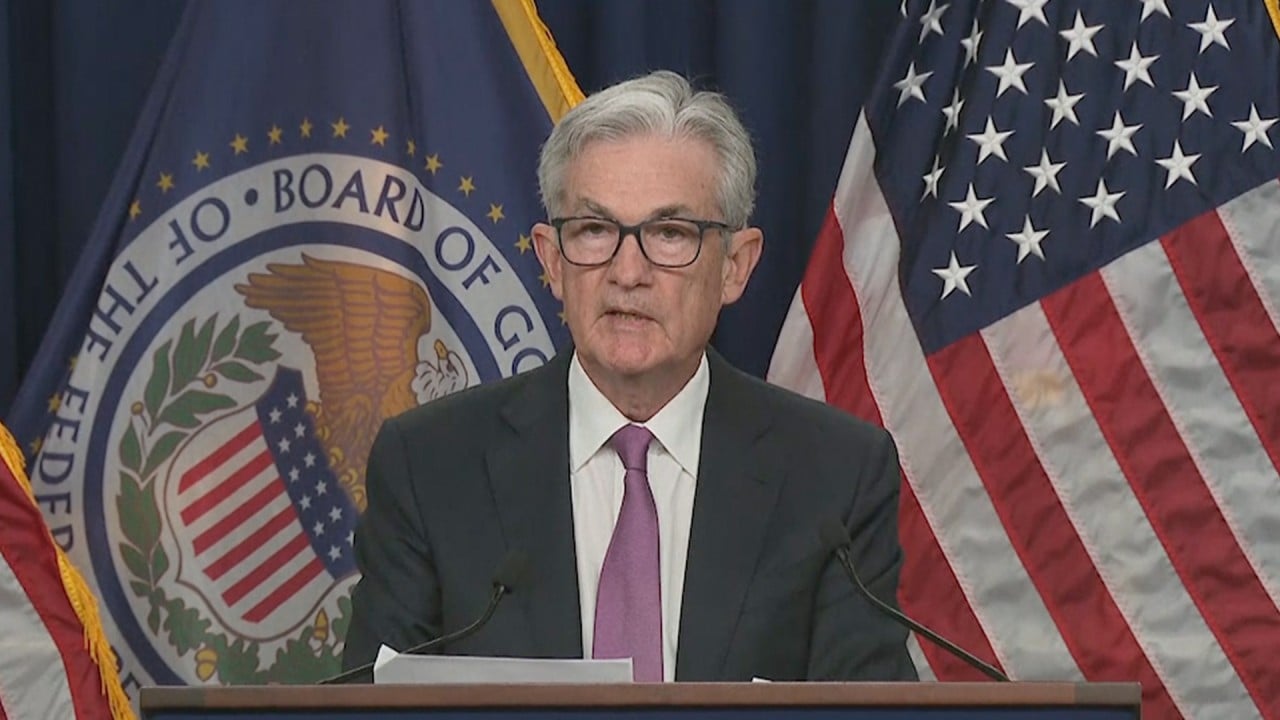

Only reinforced by the US jobs report last week, more US rate increases are in the offing. The Fed is likely to keep those rates higher for longer as it seeks to checkmate elevated inflation.

Another rise in US interest rates seems almost certain on September 21, the only question being if it will be a further 0.75 per cent move or “just” 0.5 per cent. As for quantitative tightening, how that ultimately plays out is as yet unclear, but it has to make US monetary policy more restrictive in the same way that quantitative easing was expansive.

Yuan weakness against the US dollar was less pronounced. The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) successively set midpoint rates for the dollar-yuan exchange rate last week that were numerically lower than market expectations, allowing some weakening of China’s currency against that of the US but less of a slide than the yen and the won experienced.

Japan faces a similar quandary. The yen’s pronounced weakness is, to a large degree, a consequence of higher US interest rates and continuing Japanese ultra-accommodative monetary policy, but that doesn’t mean Tokyo is comfortable with it.

“Excessive, disorderly currency moves could have a negative impact on the economy and financial conditions,” Japan’s Finance Minister Shunichi Suzuki said on Friday. “We will respond appropriately as needed, working closely with authorities of other countries.”

Is the falling Japanese yen cause for concern?

As for the prospect of coordinated action with the US authorities, never say never, but the disinflationary effect of a strong US dollar might currently suit Washington.

Over in Seoul, the Bank of Korea might not be overjoyed at the extent of won weakness versus the US dollar, but governor Rhee Chang-yong is realistic. “We are now independent from government, but we are not independent from the Fed,” Rhee said on August 28. “So if the Fed continues to increase the interest rate, it will have a depreciation pressure for our currency.”

Quite so. In the endgame of this current central bank game of chess, the Federal Reserve is the grandmaster.

Neal Kimberley is a commentator on macroeconomics and financial markets