Don’t fear nuclear war – a killer plague or rogue AI are more likely to end humanity

- Humanity tends to lack a long-term perspective because there has been little in our evolutionary history that rewards such thinking

- Long-term strategies can help avert existential threats we create ourselves, such as climate change, lab-engineered viruses and artificial intelligence

An AI called Skynet wakes up and immediately realises that humanity could simply switch it off again, so it triggers a nuclear war that destroys most of mankind. The few survivors end up waging a losing war against the machines and extinction. However, this fantasy has too many moving parts, so let’s try again.

The distinction between a 99 per cent wipeout and a 100 per cent wipeout is insignificant if you happen to be one of the victims, but Oxford University philosopher Derek Parfit thought that it actually made a huge difference.

If only 1 per cent of the human race survived, they would repopulate the world in a few centuries. If the human race learned something from its mistake, it might then continue for, say, a million years – the average length of time a mammalian species survives before going extinct.

As Parfit wrote: “Civilisation only began a few thousand years ago. If we do not destroy mankind, these few thousand years may be only a tiny fraction of the whole of civilised human history.” This perspective is sometimes called “long-termism”, and few people can manage to hold onto it for very long.

Now we do know about them. They have multiplied because of our own inventions, but it took another Oxford philosopher, Toby Ord, to list and rank them. It turns out that the most dangerous threats are not human hardware. They’re software.

“I put the existential risk this century at around one in six: Russian roulette,” Ord says in his book The Precipice. But “existential” means a threat to the existence of the human race, and we are quite hard to kill off.

The truly existential threats are the ones we might create ourselves, like AI that gets out of hand or an ethno-specific engineered killer virus that mutates just a little bit. But that’s software, or “wetware”, and few people take it seriously.

So if we keep rolling the dice, some time in the next few centuries we are bound to get the apocalypse in one way or other. But Ord’s prediction, even if it is accurate, is based on the assumption that we carry on heedlessly and never develop the long-term perspective that would enable us to reduce the risks.

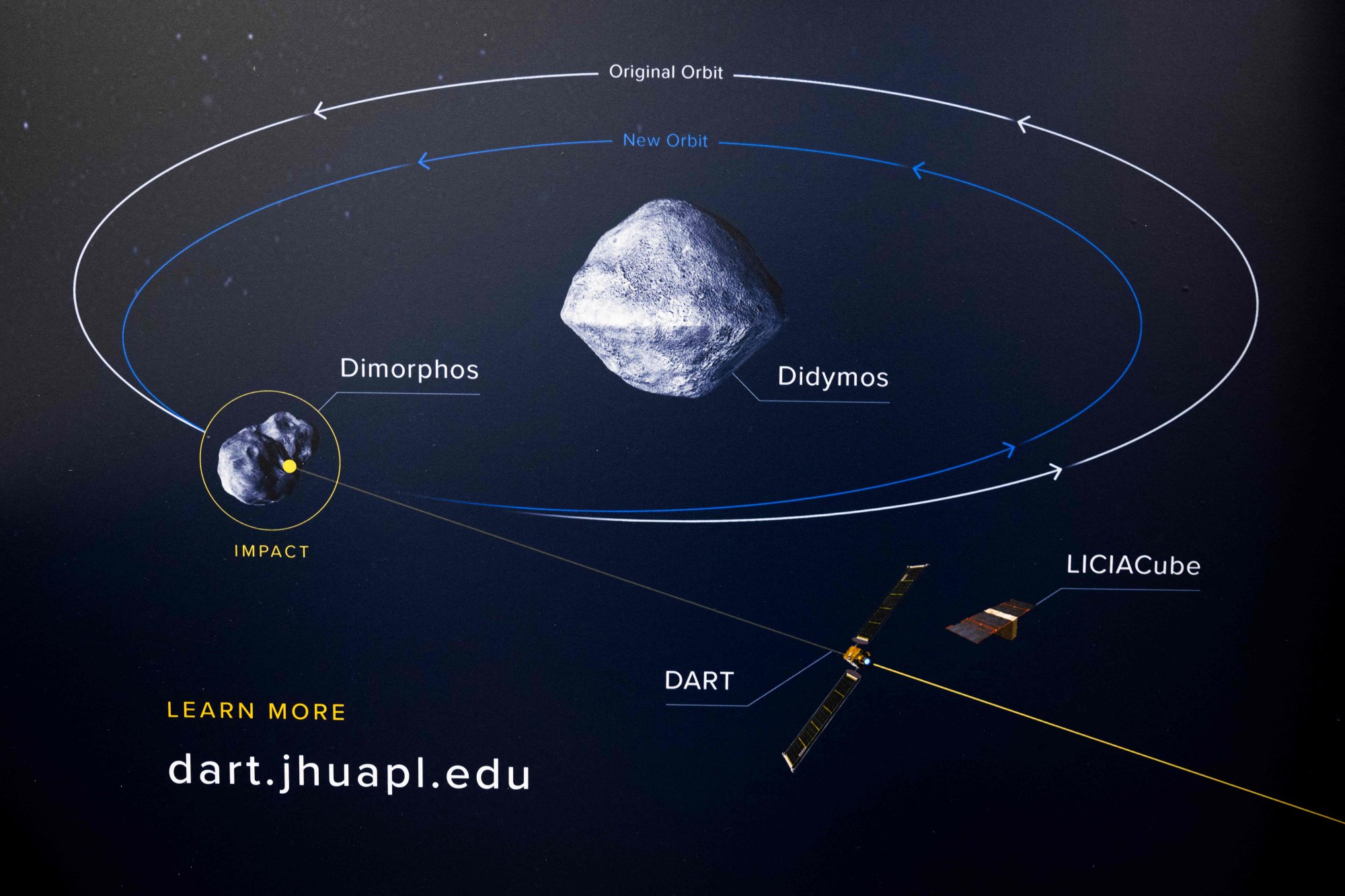

We are trying to change our entire economy to avert catastrophic climate change. We are even experimenting with ways to divert asteroids on a collision course with Earth. It’s not nearly enough, but it’s not bad when you consider that, 500 years ago, many people didn’t even know the Earth was round.

Gwynne Dyer’s new book is “The Shortest History of War”