Despite challenges, China’s quest for global leadership must end in peace

- Tensions with the US and in the region, whether with India or in the South China Sea, will limit China’s ability to exert influence far and wide. These tensions must be managed well or Beijing may opt for a more muscular projection of its power

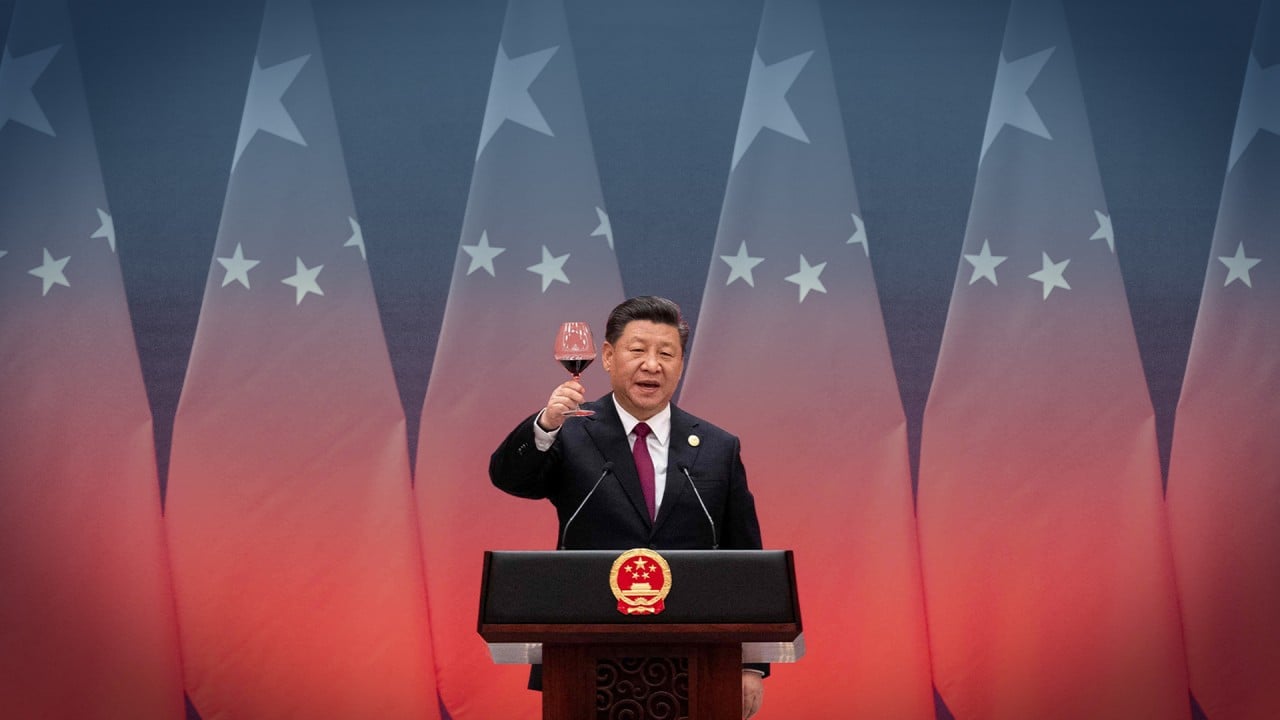

Xi now enjoys as much free rein over policy as any Chinese leader in decades and his third term will undeniably prove pivotal for China’s future.

To be sure, even as Beijing and Washington see each other as competitors on that front, tensions with the US are increasingly becoming a problem for China. For decades, China’s rise has been underpinned by its unprecedented economic growth, which itself had been facilitated by trade ties with the West – and the United States in particular. That run was derailed by the tariff war that began under US president Donald Trump.

As long as Washington sees Beijing as a competitor, those measures are only likely to escalate. Yet, it is China’s neighbourhood that arguably presents an even bigger challenge for Xi in his quest for global leadership.

Xi and Biden are at least willing to work on the US-China relationship

Over the course of his rule, Xi has seen Beijing’s relationships with its neighbours suffer, as age-old territorial disputes have heated up.

Beijing’s troubles in the neighbourhood will inevitably limit its ability to exert influence far and wide, and it’s unlikely that China can continue to play the global role that Xi desires unless he manages those tensions.

Ever hardening stances on these territorial questions will also constrain Beijing’s strategic space in the neighbourhood.

During the ongoing war in Ukraine, China and India have often found themselves on the same page – wary of alienating an important partner in Russia and dealing with the economic fallout of the war. For a considerable time now, the rise of Hindu nationalist aggression in India, along with the spillover into the diaspora, has also raised concern in the US.

Combined with New Delhi’s neutrality over Ukraine and ties to Russia, this trend has led to a few questions in Washington over India’s long-term reliability as an ally. But in the absence of an understanding over the border, China has as yet been unable to seize that window of opportunity to build a more productive partnership with India.

The one way Beijing and New Delhi could resolve border issues

Under the circumstances, therefore, Xi faces multiple trade-offs: a muscular projection of power in the neighbourhood versus a larger global footprint, and geopolitical competition with the US versus a return to economic cooperation.

China’s territorial disputes – especially in the South China Sea and the Himalayas – have increasingly become focuses of nationalist sentiment. So too have Chinese tensions with the US. However, as arguably the most powerful Chinese leader in over a generation, Xi has the political capital to make some difficult decisions with a more long-term focus.

For American diplomacy, the challenge today is to find a way to give China a bigger global voice in return for peace in Asia. If Xi struggles to assert himself on the world stage, he may well be tempted to prioritise muscularity in the neighbourhood instead.

Mohamed Zeeshan is a foreign affairs columnist and the author of Flying Blind: India’s Quest for Global Leadership