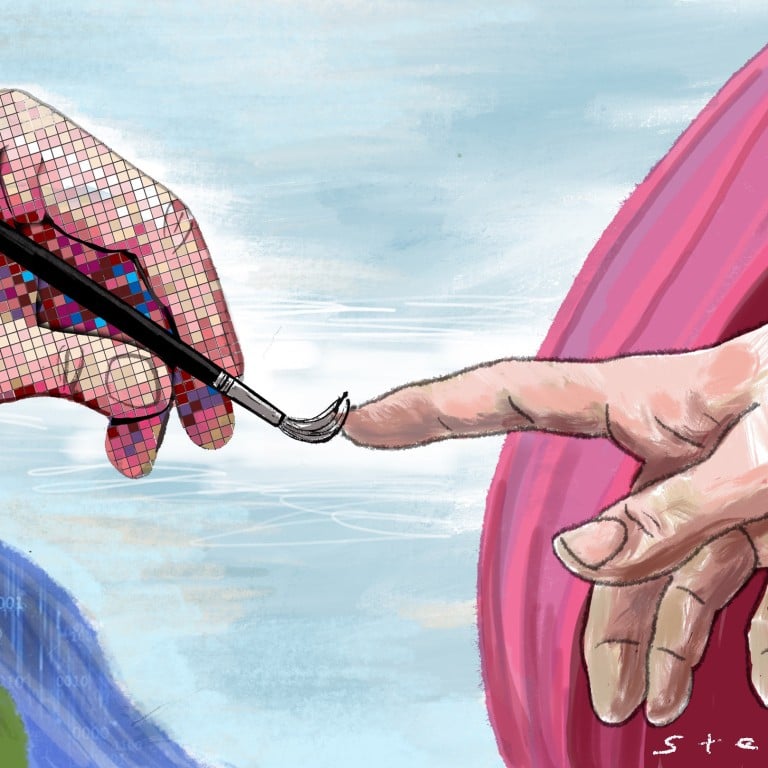

Can art generated by an unfeeling AI ever hope to move us?

- Generative AI can produce art and design much faster and more perfectly than humans ever could

- But it may be too reliant on biased search results from the internet, and it can never come up with truly great art – because it cannot feel like humans do

We were not worried. Because while supercomputers might foresee the next 100 moves in a finite environment with rules and restrictions, they could not generate creative content from scratch.

In the art and design world, we now have AI-powered visualisation plug-ins such as Veras, floor-plan adjustment software such as Testfit, and text-to-image tools such as Stable Diffusion, Midjourney and DALL-E2. We are advised to retrain to be manipulators of text prompts or left to risk losing our jobs.

Political scientist Ian Bremmer has described AI as a “weapon of mass disruption” and a top global risk this year. Over the years, other bright minds have also warned about the dangers of AI, including physicist Stephen Hawking, Tesla CEO Elon Musk and DeepMind founder Demis Hassabis. Specifically, they warned about the spread of misinformation and biases.

How would AI become biased? To generate output, AI requires input, including information from the unchecked and unregulated internet. As Bremmer explained: “The internet offers so many points of view that only the loudest and most provocative gain large-scale attention.” What if the “loudest and most provocative” views, rather than facts, are fed into the machine?

As Who’s Raising The Kids? author Susan Linn pointed out, an online search for “black girls”, “Asian girls” and “Latina girls” used to turn up pornography in the top results. Only recently did Google fix the bias, after trying to justify it as a reflection of societal prejudices. If machines cannot recognise bias and provide reliable results, how can they transcend that function and provide creative content that is responsible, useful and compassionate?

In engineering problems, there tends to be a right and wrong. But art and design can only be good or bad – and sometimes both. Satisfaction with AI-generated art or design lies in the eye of the beholder, whether clients or commissioners. Great architecture mesmerises, not because it is perfectly conceived and realised, but because it hits a nerve and evokes an emotion.

Without modern efforts, these world-famous buildings would long have crumbled to the ground. To appreciate creativity, we have to appreciate the good, the bad and the intrinsic ideas of the works produced by flawed human geniuses.

In contrast, generative AI does not have human feelings. It can pretend or claim it has them, but it would not comprehend love, loss, happiness, sorrow, sympathy, empathy, taste, pain, hunger or any trait essential to humanity. It can come up with technically perfect solutions but would fail to establish an emotional connection.

According to social and behavioural scientist Michael D. Slater and mass communication expert Donna Rouner, “Human beings are social information processors before they are processors of facts, figures, and logical arguments”. Maria Konnikova elaborated further in The Confidence Game: “Our emotional reactions are often our first. They are made naturally and instinctively, before we perform any sort of evidence-based evaluation.”

Accordingly, we often cannot explain explicitly what we like or dislike about something, only that we know how we feel about it – whether it’s a piece of music, a play, film, painting or sculpture. True creative works require a much deeper human touch.

But we should not be anti-AI. We should adopt technology to help us perform at our best and maximise our potential. We can delegate repetitive and labour-intensive tasks to it while elevating our own thinking. We should ask ourselves what we aspire for in creativity – it takes common sense and a rational market to differentiate between the products of compassion and those of algorithmic decisions.

Even if machines can rival the complexity of the creative human brain and show a superintelligence beyond our imagination, they would still not be born in flesh and blood; they would still not be able to develop human emotion. The world enjoys creativity, and all the more so when the artistic product is attuned to its maker’s singular world view and experience.

AI could probably produce a large volume of work without ever being truly creative. But unlike human artists, its ego cannot be hurt – after all, it cannot feel a thing.

Dennis Lee is a Hong Kong-born, America-licensed architect with years of design experience in the US and China