Political shake-ups in Thailand and Turkey unlikely to spring foreign policy surprises

- The opposition in power will be restrained by contentious domestic politics, a growing ‘multi-alignment’ consensus and the sheer value of strategic and economic ties with China

This year, two pivotal states in Asia faced their most consequential elections in recent memory. Although perched at opposite ends of the continent, Thailand and Turkey share much in common, prompting some political scientists to describe them as “unlikely twins”.

Turkey and Thailand are regional powers with dynamic export-oriented economies. They are also US treaty allies. Yet, Turkey and Thailand have maintained warm ties with China and other Eastern powers.

Crucially, the nations share a long history of military coups against democratically elected governments and have been under the thumb of strongman populist leaders in recent memory.

But even if the opposition manages to capture power, with Thailand facing contentious coalition-building parliamentary politics and Turkey heading into a polarising run-off presidential election, it’s unlikely that either country will radically alter its foreign policy direction.

By all indications, both nations will optimise their prized position as “pivot states” in the 21st century – deftly balancing relations with the West and East to maximise national interests.

Still, opposition leaders in both nations have indicated, as part of their anti-establishment campaigns, their commitment to alter foreign policy once in power.

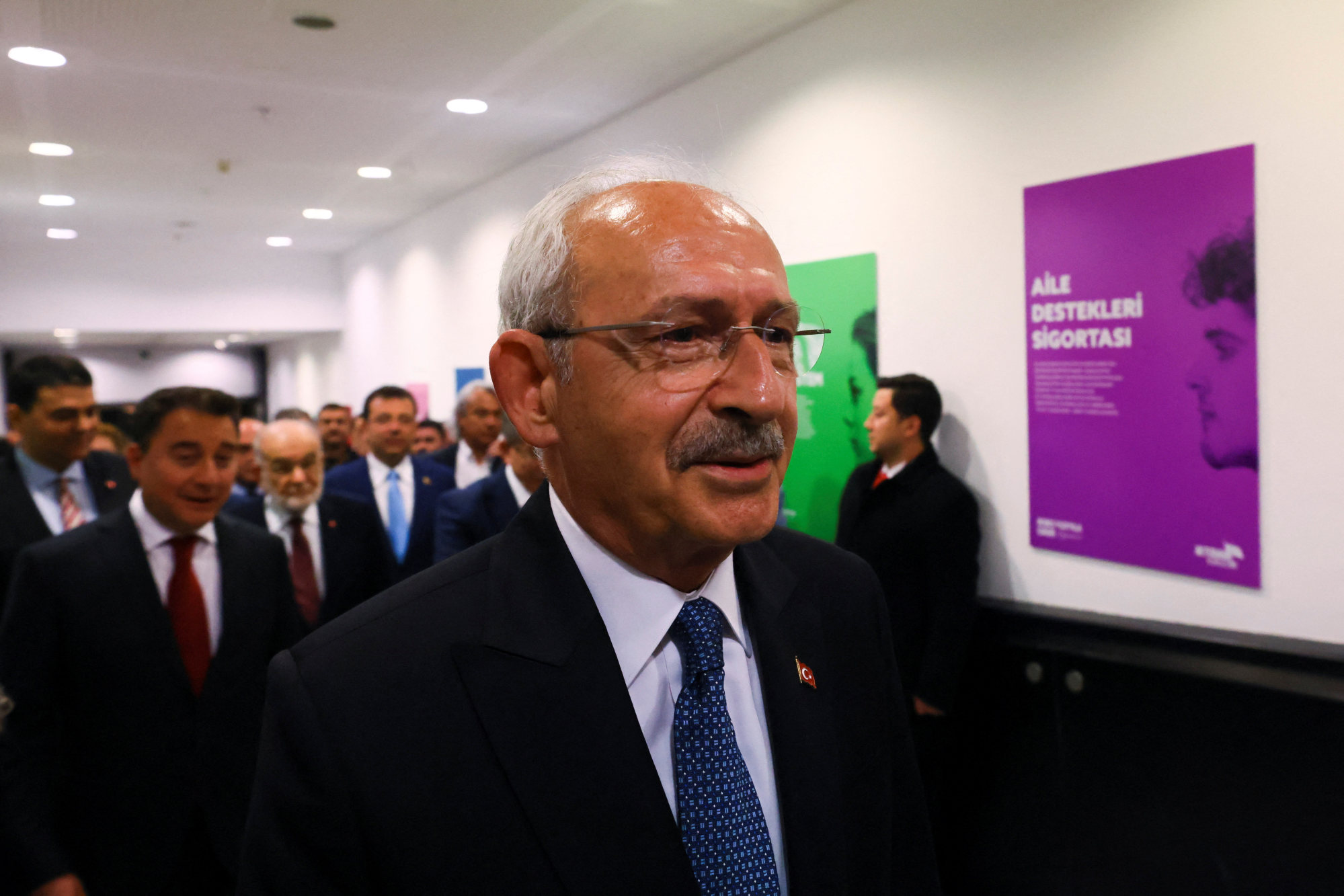

Turkey’s main opposition leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu has advocated a more Western-friendly strategic orientation than the incumbent Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Still, there are three main reasons to be sceptical about a radical reorientation of Thai and Turkish foreign policy soon. To begin with, opposition groups face extremely contentious domestic politics even if they dislodge their conservative rivals.

Even with the most seats in the lower house of the Thai parliament, the youthful party is still not assured of forming the next government, given the lingering risk of a counter-coalition backed by the military-appointed Senate’s backing. And even if the party leader, Pita Limjaroenrat, becomes the next prime minister, he faces the threat of yet another military coup should he attempt to implement his most radical policies.

In Turkey, Kilicdaroglu, even if successful in the run-off elections, will face a still-powerful Erdogan, who will continue to wield tremendous influence through parliamentary allies and an army of appointees across key state institutions. The opposition leader will also have to contend with raucous allies who temporarily backed him only out of shared antipathy towards Erdogan.

Can Turkey’s divided opposition oust Erdogan from power after 20 years?

This brings us to the second major factor, namely the strength of an increasingly “multi-alignment” consensus in both countries.

Crucially, China has conducted war games with both Thailand and Turkey, as the two Asian nations seek to diversify their defence relations beyond traditional Western allies. Although both nations are expected to experience major domestic political tremors, their overall foreign policy orientation is likely to remain predictable for now.

Richard Heydarian is a Manila-based academic and author of “Asia’s New Battlefield: US, China and the Struggle for Western Pacific”, and the forthcoming “Duterte’s Rise”