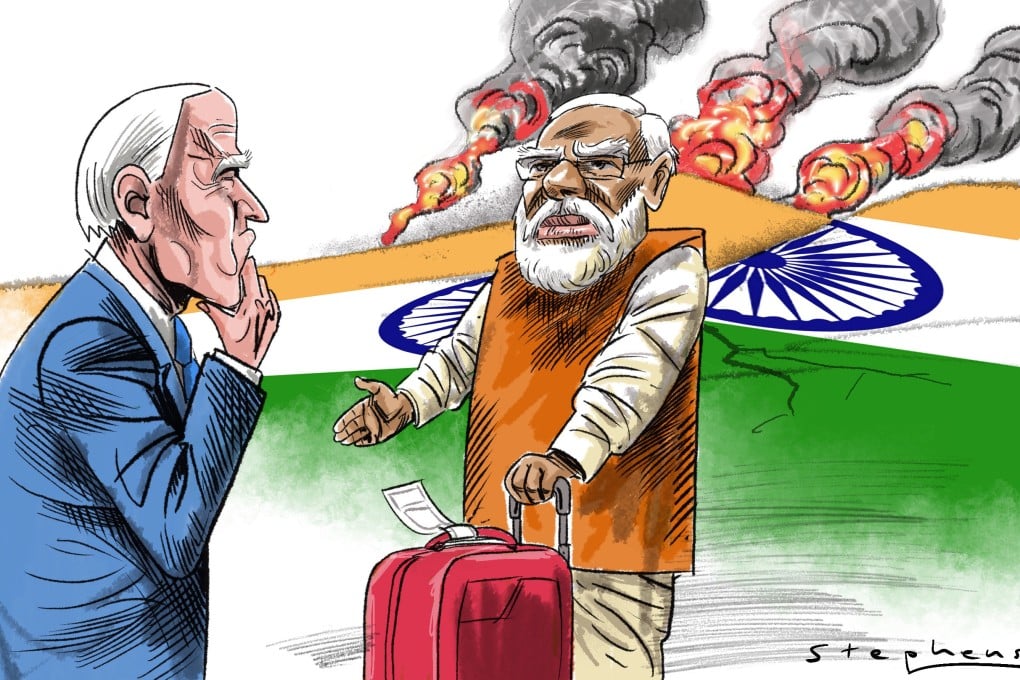

Opinion | For India to be an effective partner to the US, it needs stability at home

- Massive troop deployments in Kashmir and more recently in the state of Manipur strain India’s already inadequately funded military

- This could make New Delhi less willing to commit support to Washington against Beijing, which in turn could decrease US congressional support for a defence partnership

Washington hopes that a stable, democratic India will counterbalance China’s influence in Asia and work in tandem with US strategic interests. For that, the US believes that bolstering India’s military is essential.

Meanwhile, Modi has been trying to enhance India’s hard power. Capital spending on defence has been increasing since he came to power. In the 2023-24 budget announced in February, India allocated 13 per cent more funds to the defence sector than in the previous year.

Some of India’s expenditure on defence has already borne fruit. This month, the navy put on display a new indigenous aircraft carrier, which should become fully operational later this year, in an exercise involving over 35 aircraft. Modi now hopes to sign a deal with the US to co-produce jet engines for Indian fighter aircraft.

Yet, despite this incremental progress, India’s military forces remain heavily overburdened. Notwithstanding increased spending, India’s defence sector has suffered a massive shortfall between funds allocated and the military’s needs over the past five years. There have long been concerns that the country’s naval fleet is reaching obsolescence and that the strength of the air force’s fighter squadrons is declining.