Advertisement

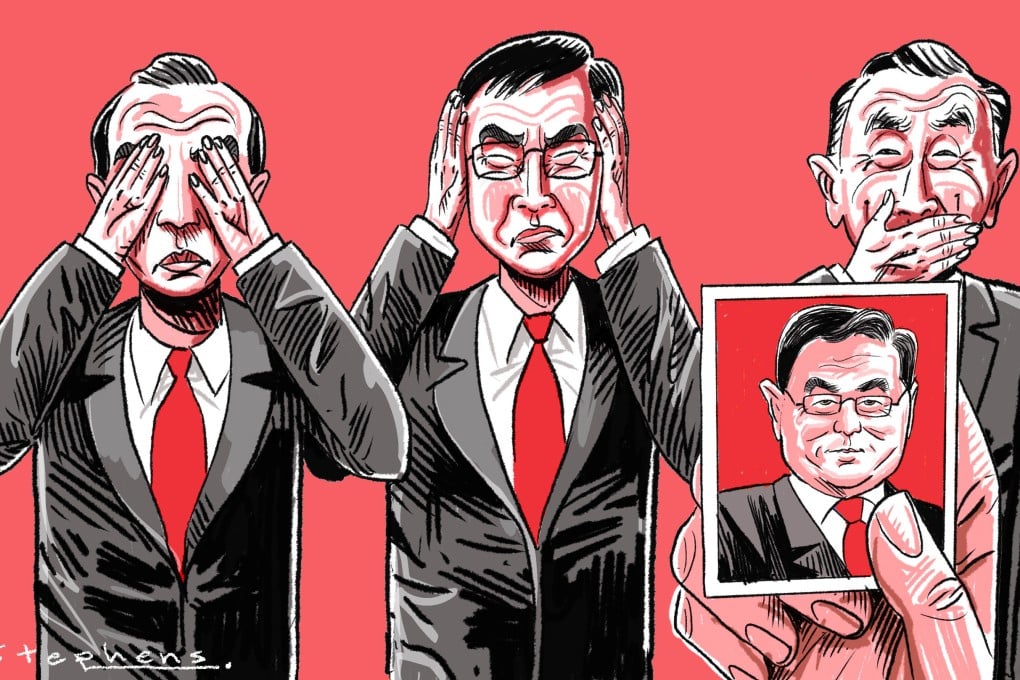

Opinion | Stony silence over Qin Gang saga does China’s reputation no favours

- If Beijing had come clean about the reasons for Qin’s dismissal and been willing to address media questions, it might have incurred nothing more than embarrassment

- Stonewalling on the issue has instead damaged China’s image as a responsible world power

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

61

It is like watching a political satire show, except that it’s not. Qin Gang, China’s newly minted foreign minister and a high-flying political star, has disappeared from public view since June 25.

Speculation about his political future and personal well-being started to gather pace after a Foreign Ministry spokesperson claimed on July 11 that Qin was unable to attend the Asean foreign ministers’ meeting due to “health reasons”.

That claim came after Beijing postponed a trip by European Union foreign policy chief Josep Borrell, scheduled for the second week of July. Borrell was supposed to meet Qin to reduce misunderstandings between the two sides.

In the ensuing two weeks, speculation about Qin’s whereabouts has become more intense but China’s state media remains conspicuously silent.

Foreign Ministry spokesperson Mao Ning drew the short straw and had to face Qin-related questions at the daily press briefing. From the short videos being circulated online, one could feel the farcical awkwardness in the air whenever a Qin-related question arose.

Often, for a few seconds, Mao would pretend to look at and reshuffle her prepared notes or ask a reporter to repeat the question before giving her standard reply: “I don’t have any information to offer”, or “I have no knowledge of that issue”.

Advertisement