China’s belt and road will still focus on hard infrastructure, whatever Beijing says

- A professed shift in focus from hard infrastructure to ‘institutional connectivity’ is laudable but unlikely to happen

- The open nature of the belt and road deters efforts to shape it into a more binding platform, and Chinese companies are likely to cement their foothold in the industry by building more, not less

This “soft” connectivity, as opposed to the “hard connectivity” of roads and bridges, is essential for sustainable development and regional integration.

Since at least the 1990s, Western development finance has focused on the soft, institutional side of development, while Beijing’s approach has been characterised by financing for big, physical infrastructure projects. If the belt and road were to switch focus to soft connectivity, it would mark a departure from Beijing’s traditional approach.

But this narrative of a belt and road 2.0 focused on institutional connectivity and smaller, more sustainable projects overlooks that the initiative is still very much about building hard infrastructure, and that it is likely to continue in this vein.

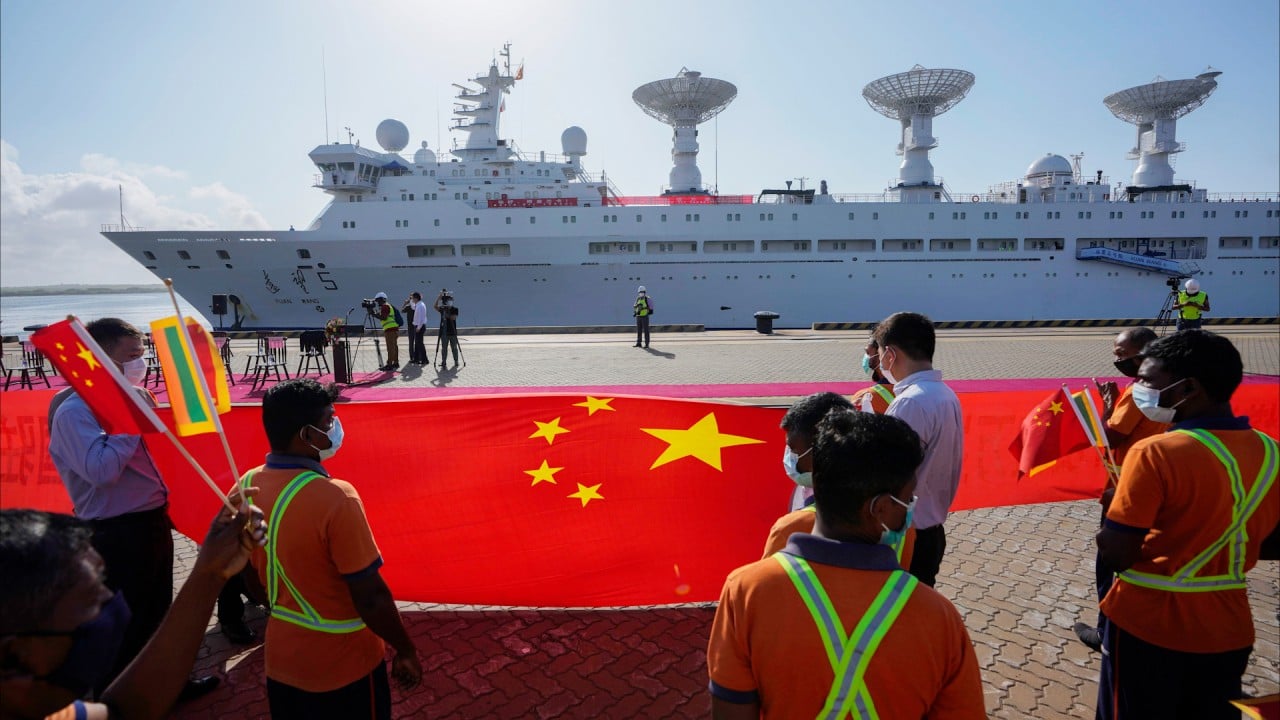

For starters, the belt and road encompasses billions of dollars worth of infrastructure projects financed by non-Chinese sources, but built by Chinese companies. For instance, the Chinese-built Pelješac Bridge is held up in the white paper as an exemplary project, despite involving no Chinese capital and being funded by European Union grants.

Beijing tends to emphasise the inclusive, open nature of the belt and road, but the one thing all projects have in common is the involvement of a Chinese company. Rather than Chinese funding, this is the one, unifying characteristic of belt and road projects.

The first decade of the initiative has been characterised by Chinese loans for projects, which have been tied to the use of Chinese companies. China Road and Bridge Corporation, for example, has won many lucrative contracts on the back of Chinese state financing for the belt and road.

In the 1990s, and with the “Going Out” policy of the 2000s, Beijing tried to help Chinese companies secure a foothold in global markets. The belt and road is Going Out 2.0, plus a more compelling narrative.

Over the past 10 years, Chinese companies have built on the footholds they secured in the 1990s and 2000s to become globally dominant. In 2012, a year before the belt and road was launched, CRBC’s parent company, China Communications Construction Company, ranked 10th on ENR’s list of top 250 international contractors. In 2022, it was 3rd, alongside 78 other Chinese companies in the top 250.

However, this doesn’t spell the end of the focus on hard infrastructure. The 2022 belt and road investment report from the Green Finance and Development Centre showed that Chinese companies’ contract revenue from the belt and road remains robust, and that investment from private enterprises might be helping to fill the gap left by Chinese policy banks.

10 years of China’s Belt and Road Initiative

In addition, Beijing has a long way to go to solidify the soft, institutional side of the initiative. Ultimately, the belt and road is not an actual grouping or platform – there is no international body guiding it, no concrete blueprint, or even fixed criteria for what constitutes a belt and road project.

Two “cooperation priorities” are policy and trade connectivity – areas that should be focused on soft infrastructure, but on this front, the belt and road’s accomplishments are limited.

Membership of the belt and road itself also follows this pattern: to be included among the belt and road family of countries, it is necessary only to sign a non-legally binding memorandum broadly signalling willingness to engage in belt and road cooperation.

Beijing wants to keep the belt and road as open and flexible as possible, and there is certainly merit to this, but it also makes it hard to develop the initiative into a more sophisticated platform for connectivity, as Beijing wants to.

Still, this might not be such a tragedy. Hard infrastructure is in just as much demand as the soft stuff. But, if the second decade of the belt and road continues to be about building highways and wind farms, the main loser will be Beijing, which will have missed a trick in staking a stronger claim to global leadership.

Jacob Mardell is an analyst at the Mercator Institute for China Studies