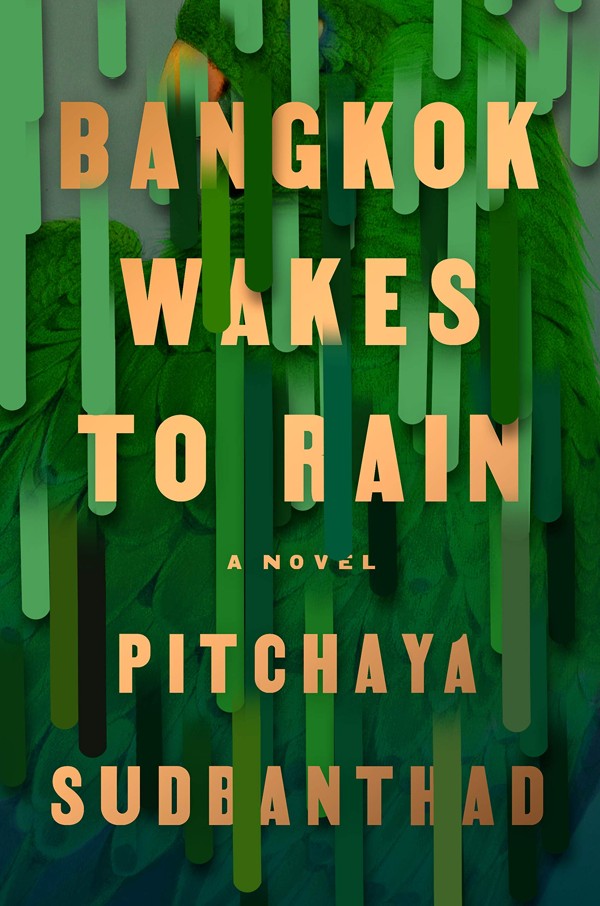

Review | Bangkok, capital of Thailand at the mercy of floods, brilliantly evoked in debut novel about its past and future

- The chapters, not just the waters, flow back and forth in time in expat Thai Pitchaya Sudbanthad’s dazzling debut novel Bangkok Wakes to Rain

- A grand house in the city is the backdrop to an exploration of the city’s relationship to water and its past, and imagines its future

Bangkok Wakes to Rain, by Pitchaya Sudbanthad, Riverhead, 4 stars

Bangkok Wakes to Rain should come with a mop. This teeming debut novel by Pitchaya Sudbanthad recreates the experience of living in Thailand’s aqueous climate so viscerally that readers will feel the water rising around their ankles.

Why Indians owe most of their genes to migrants from what’s now Iran

But Sudbanthad’s skills are more than just meteorological. A native of Thailand now living in New York, he captures the nation’s lush history in all its turbulence and resilience. Even the novel’s complex structure reflects Bangkok’s culture. The chapters flow back and forth in time, in ways that may leave readers initially grasping for solid ground.

The earliest sections involve an American doctor working for a Christian mission in 19th century Siam. He’s a reluctant volunteer, shocked by the primitive conditions and sceptical that these pagans will ever be brought to the light of science or God.

His first reaction is to plead for a transfer away from this quagmire. “The waterborne city inspirits our undoing,” he writes to his brother back in New England. “Its fluvial systems – the natural ones and also the mesh of canals throughout the capital – carry to us miasmata that weaken the body.”

His attitude towards the people is no less biased, dripping with the common racism of his time and station: “The Siamese as a race thrive in the aquatic realm,” he complains. “They live is if they have been born sea nymphs that only recently joined the race of man.”

How this doctor’s attitude will change over the years and how the city will evolve over the centuries are just two of the themes dissolved in this extraordinarily fluid novel.

Characters come and go, washed away by the tides of time, but at the centre of Bangkok Wakes to Rain remains a grand house built by the son of a labourer who founded a trading company and grew rich. We see this building with its flowery tiled ceiling in varying conditions in different periods.

How Aladdin’s original Chinese identity was lost in Hollywood

In one, it’s the home of a wealthy divorced woman who lives with a gathering of ghosts that only live music can exorcise. In another era, the house has been overtaken by a high-rise condo development – the facade of the original Sino-Colonial dwelling reduced to decoration in the glitzy new lobby. And later still, decades ahead in the 21st century, the building is subsumed by the rising sea that has overwhelmed, but not snuffed out the capital.

The connections between these stories are sometimes clear, sometimes opaque, a structure that demands an extra degree of tolerance (a few brief chapters are told from the perspective of birds) . But allow yourself to sink into that ambiguity, and you’ll find Bangkok Wakes to Rain entrancing. Individual incidents are dramatic and striking. A substantial section involving two Thai sisters in the late 20th century named Nee and Nok is among the best. Nee barely escapes the deadly repression of student protests in the 1970s, while Nok settles in Japan and opens a Thai restaurant. Thousands of miles away from home, she imagines she can just dabble with the ingredients of her native culture, but the moral burden of her past eventually finds her out.

Although Thailand is among the countries at greatest risk from the effects of global warming, it’s also among the places most familiar with flooding. That long experience may help the government respond, but the swelling climatic crisis will exacerbate other social and economic challenges, an eventuality that Sudbanthad explores as his novel moves into the future. Levies breach and foundations turn spongy.

As we watch Bangkok grow into a spectacularly modern city, the old burdens of racism and class mutate into new toxins. The richest citizens can afford to float above the ever-rising sea, but they can’t escape the anxiety of their positions nor the germ of self-loathing. In one poignant story, a fifth-grade girl worries that the sun may darken her skin, while nearby her father, an esteemed plastic surgeon, carves the faces of Asian women into the Western ideals they crave.

“Anything has a way of disappearing,” one narrator says. In the final scenes – infused with futuristic technology for some and unfathomable suffering for others – we see a city racing to digitise itself, to transfigure people and objects into an incorporeal state beyond the water’s reach. It’s a vision oddly terrifying and ethereal, and another demonstration of this author’s extraordinary range, flowing gracefully from historical fiction to contemporary realism to science fiction.

Sudbanthad’s narrative is not just a tribute to his home, it’s an act of resistance against the city’s mildew and amnesia: Bangkok’s unwillingness to retain what came before. These stories, loosely linked together, become a way of preserving what is otherwise inscribed only on the liquid surface of memory.