Chinese appetite for fish maw drives ‘panda of the sea’ to brink of extinction, and fuels illegal trade from Mexico to China

Wildlife crime group digs deep into illegal trade through Hong Kong and other Asian ports in the maw of the endangered totoaba fish, a trade that has doomed the vaquita, world’s smallest porpoise, to almost inevitable extinction.

Its name in Spanish means “little cow” but it’s also been called the “panda of the sea” because of the black rings around its eyes. It is the world’s smallest porpoise – and the most endangered marine mammal on the planet, thanks to Chinese and other East Asian diners’ appetite for part of an endangered fish that swims in the same waters off Mexico.

Is a HK$2 billion love of fish maw worth endangering a species?

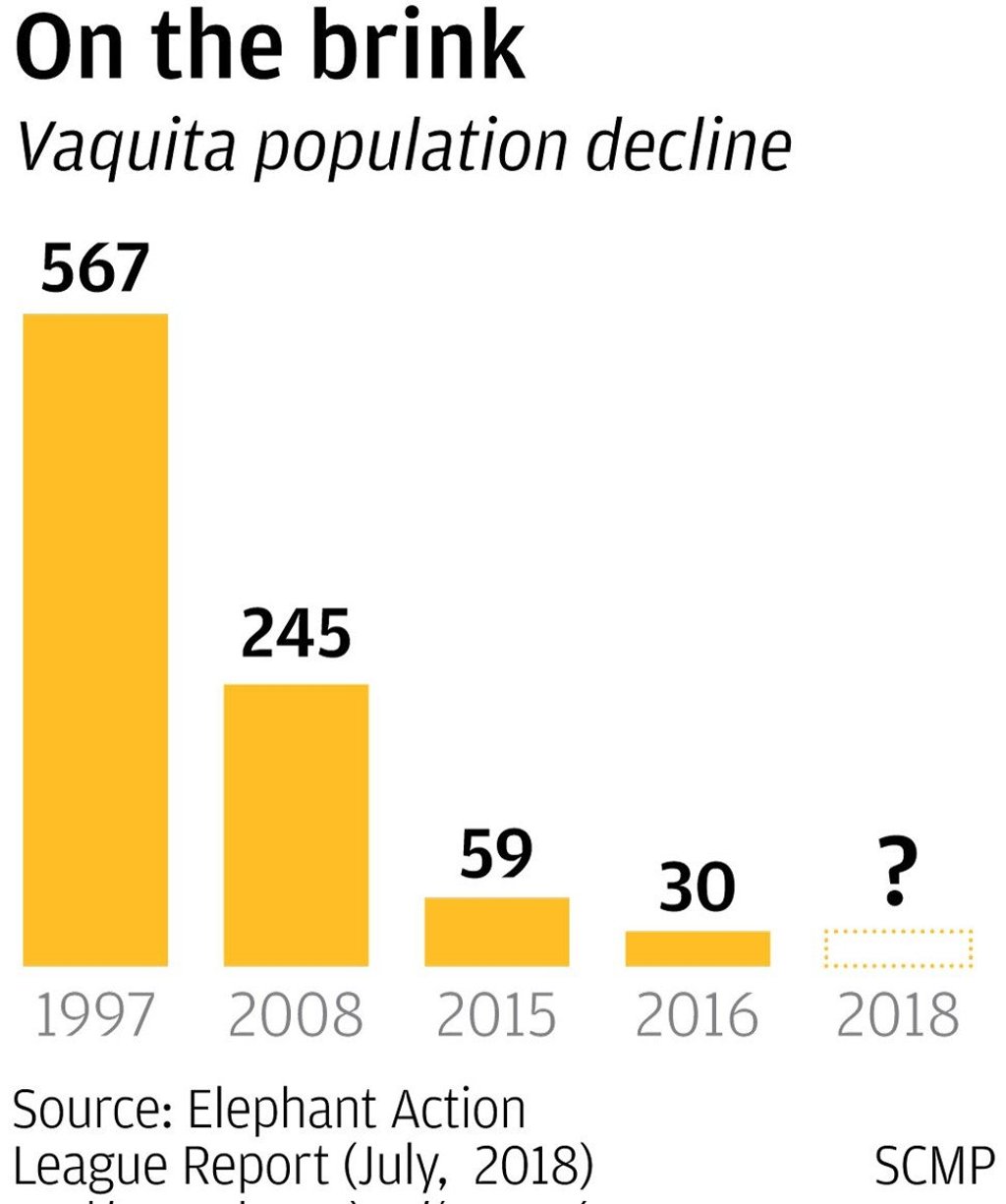

Vaquita numbers in the Sea of Cortez, in the Gulf of California off Mexico’s west coast, where its habitat is ostensibly a protected marine reserve, have plunged by 90 per cent since 2011, global conservation organisation WWF says. The porpoise, which grows to 1.5 metres and weighs a little over 40kg, is endemic to the gulf – meaning it lives nowhere else – as is the totoaba.

“Nobody knows exactly how many [vaquita] are left,” says Hong Kong-based Gary Stokes, Asia director for conservation group Sea Shepherd.

“Anywhere between 12 and 30 is the population estimate. Numbers have been diminishing for the past 20-30 years … there’s little hope for the species’ survival.”

Fishermen earn more in one night for catching a few totoabas than they can otherwise earn in a year, the EAL report says.