How an activist Buddhist convinced Thai king law on insulting monarchy was being abused

- Sulak Sivaraksa, proponent of engaged Buddhism, talks about how an audience with King Maha Vajiralongkorn led to a halt in new lèse-majesté cases in Thailand

- Lèse-majesté, or insulting the monarchy, is punishable by three to 15 years in prison in Thailand

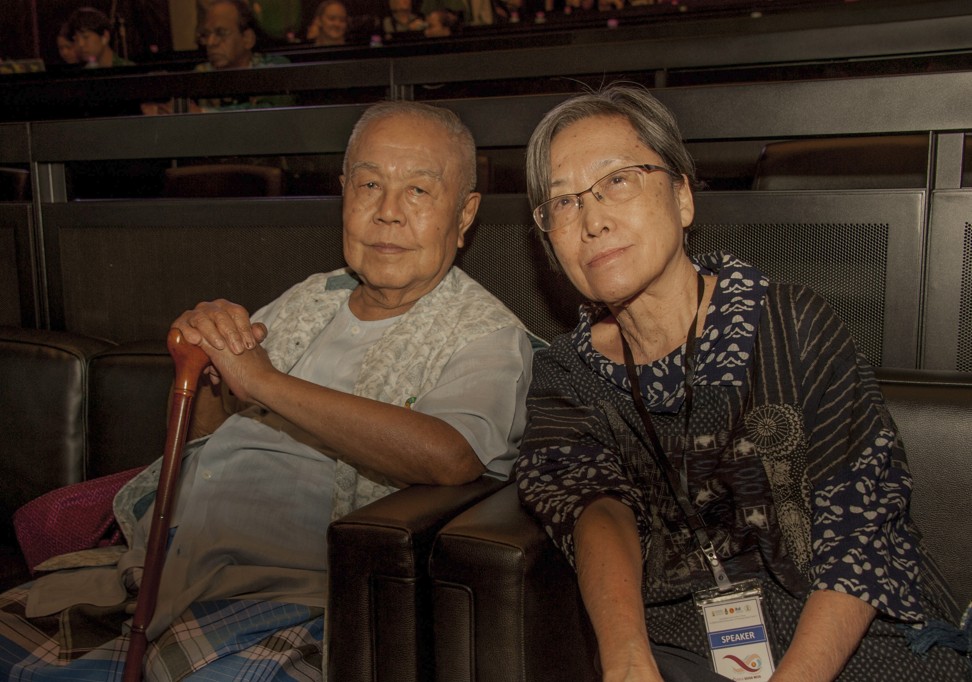

“Sombath is a good friend of mine,” says Sulak, who at the age of 86 remains Thailand’s best-known political gadfly. His long career as a social critic and activist has driven him into exile twice and seen him embroiled in numerous court cases.

Sulak has been campaigning for Laos’ communist government to release Sombath, 67, since his mysterious disappearance. Before he vanished, Sombath was the country’s foremost promoter of community development initiatives, launching numerous grass-roots projects in education, micro-enterprise and eco-friendly farming.

“He served his people wonderfully, training young people to be useful to Laos, and the government responded to his good work by kidnapping him,” Sulak says. Vientiane has repeatedly denied knowledge of Sombath’s whereabouts.

For Sombath, like many social activists in Southeast Asia, Sulak was a mentor.

A prime minister who modernised Thailand, a diplomat who broke the ice with Mao’s China

“Sulak was a very important influence in Sombath’s life, especially his work on engaged Buddhism and how to use engaged Buddhism to pursue what is right, what is just for disenfranchised groups,” says Ng Shui Meng, Sombath’s Singaporean wife, referring to the application of Buddhist precepts to social and political injustices.

Sulak, best known abroad for his trials and tribulations with Thailand’s onerous lèse-majesté law – under which insulting leading members of the royal family can lead to imprisonment for up to 15 years – is first and foremost a proponent of engaged Buddhism.

Sulak was a founding father of the International Network of Engaged Buddhists (INEB), established in 1989, with patrons including The Dalai Lama, Vietnamese activist monk Thich Nhat Hanh and Cambodian monk Maha Ghosananda.

Sticking to a Buddhist foundation for his intellectual and activist work in Thailand, a predominantly Buddhist country, has arguably helped keep Sulak out of prison.

Loyalty Demands Dissent, Sulak’s autobiography, was published in 1998, soon after he was acquitted of a lèse-majesté charge brought against him in 1991 that forced him into self-exile (1992-1995).

This year, two English-language biographies have been published on Sulak: ROAR, Sulak and the Path of Socially Engaged Buddhism by Matteo Pistono, and Hidden Away in the Fold of Time: The Unwritten Dimension of Sulak Sivaraksa by Pracha Hutanuwat. “I am getting famous in my old age,” he jokes.

For me, human beings must have the right to speak their minds. Without the right to speak your mind, you are not a human being.

Sulak – who, like many Bangkok-born Thais, is of Chinese descent – stands out for his outspokenness and fearless criticism of authorities, whether they be in the military, monarchy or the Sangha, the Buddhist monastic order.

“He’s a provocateur, and I think this is a very important role to play in a society that has people who want to discipline it all the time top-down,” says Chris Baker, a Bangkok-based historian who, with his Thai wife, Pasuk Phongpaichit, has written a number of books on Thai history and literature.

“It is important to have people who have the guts to challenge that [authoritarianism] but also, somehow, have the ability to survive, which to me is attributable to the sheer strength of his character.”

Sulak was born into a middle-class, Sino-Thai family in 1933. His father was an accountant at the British American Tobacco company.

“My character started with my own father,” he says. “He encouraged me to be myself.”

The second-most influential force in his early years was Buddhist monk Bhaddramuni of the royal Thongnopphakhun temple, where Sulak became a novice monk during the second world war.

“He introduced me to Buddhism and Siamese culture. Without him, I’d be like any other Thai, influenced by mainstream education, fashion and Americanisation,” Sulak writes of his mentor in ROAR.

Sulak entered Bangkok’s Assumption College, a training ground for the business community, before going abroad to study at the University of Wales, in the United Kingdom. He spent eight years in the country, occasionally working for the BBC and eventually becoming a barrister in 1961.

“This became the turning point for me with the king,” Sulak writes in ROAR.

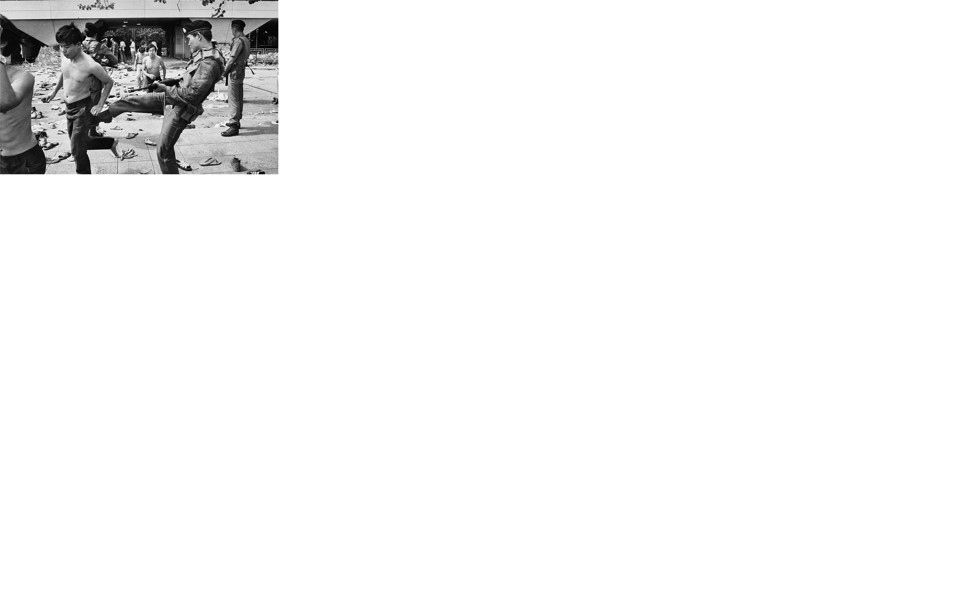

Sulak was in the UK during the bloodshed, and decided to stay abroad for a year after his bookshop and publishing house in Bangkok were ransacked.

Thereafter he faced several charges of lèse-majesté, for comments he made in public about Bhumibol and the institution of monarchy. He was acquitted on all charges.

Sulak was granted a rare audience with Vajiralongkorn in December 2017, after the two met informally at an honorary degree granting ceremony at Thammasat University.

During a photo shoot following the ceremony, Vajiralongkorn and Sulak swapped pleasantries.

Sulak’s become, in some way, untouchable. He’s so well connected to the rest of the world that to take him on legally always becomes an international incident.

“He said, ‘You have many good ideas. Why don’t you come and advise me. I thought he was joking, but on December 3, 8pm, the telephone rang. The royal secretary asked me if I was free on December 5 at 8pm,” Sulak says.

His audience with the king lasted 90 minutes. Vajiralongkorn asked Sulak’s opinion on three issues: the lèse-majesté law; the future role of the monarchy in Thailand, and; whether democracy was suitable for the kingdom.

On lèse-majesté, or Article 112 in the Thai Penal Code, Sulak said the law was often abused by people in power and ended up tarnishing the monarchy more than protecting it.

“There has not been a new case of lèse-majesté since October 2017,” says historian David Streckfuss. “What the new king has done, effectively, is removed the much abused tool that the military and Bangkok elite have used against their critics.”

10 Thais gagged by lèse-majesté law, used by junta against critics of its rule

The law has yet to be amended, however.

“The point is that the government should do something legally,” Sulak says. It is up to Thai legislators to amend the law, or replace it with a less onerous one that would protect the monarchy against libel.

Whether the newly elected government will have the courage to do so remains to be seen.

In Thailand, few people have shown the same courage as Sulak, Streckfuss says.

“Sulak as a social critic, a political critic, has almost stood alone,” Streckfuss says. “He’s become, in some way, untouchable. He’s so well connected to the rest of the world that to take him on legally always becomes an international incident.”

Looking back on his unique career, Sulak takes a more Buddhist view of his achievements.

Thai academic cleared of lèse-majesté after questioning legendary war story

“My achievement is I have kalyana-mitta (spiritual friends) – good friends who tell me what I don’t want to hear, and I have friends all over the world,” he says.

Being open to criticism, Sulak’s lifelong message to authorities is that they should be mindful of the opinions of others.

“For me, human beings must have the right to speak their minds. Without the right to speak your mind, you are not a human being,” he says.