Chinese gold miners’ bones in 1902 New Zealand shipwreck: should they be raised for burial or left under sea now they have been discovered?

- In 1902 the SS Ventnor, carrying the remain of gold miners back to China, sank in the Tasman Sea. The bones of some have been found in the wreck of the ship

- The leader of the divers who found them believes they should be brought up and buried in China, but members of New Zealand’s Chinese community don’t agree

Nothing could have prepared Keith Gordon for the image he witnessed on the small video display in the cabin of a vessel anchored in the Tasman Sea, about 25km southwest of Hokianga in New Zealand’s North Island.

“When I looked at the screen, I just thought, ‘bloody hell’,” says Gordon, one of New Zealand’s most experienced underwater explorers.

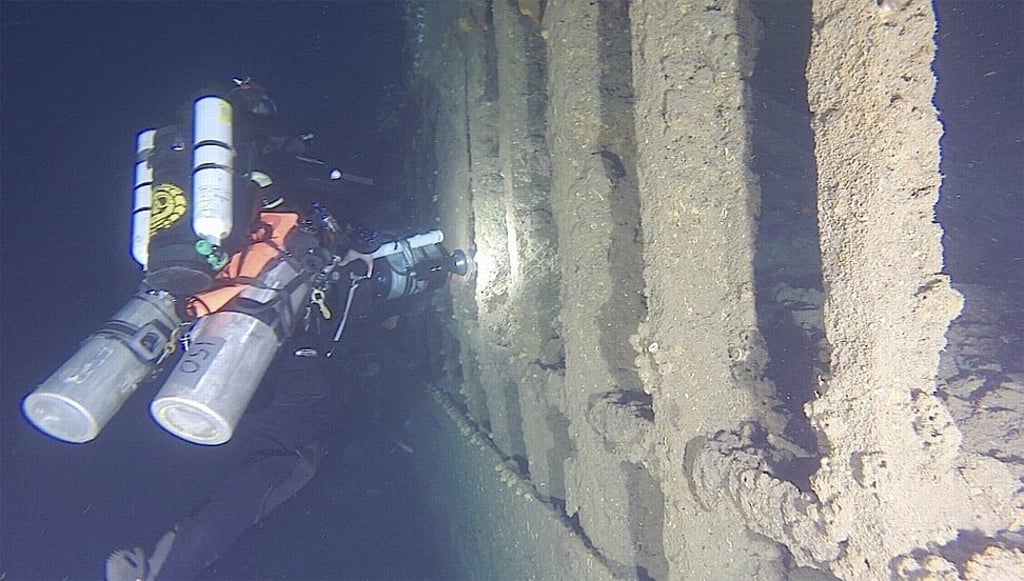

Some 150 metres beneath where he stood, a yellow, remotely operated underwater vehicle was searching inside the wreck of the steamship SS Ventnor and sending real-time video footage to the surface. As the vehicle descended, its lights illuminated a chilling spectacle.

“There were skulls and bones just lying there; it was a surreal moment,” says Gordon, who, with leader John Albert and colleague Dave Moran of the Project Ventnor Group, had been working for almost nine years towards this moment.

They were observing the skeletal remains of some of the 499 (some reports say 489) Cantonese gold miners the SS Ventnor had been transporting from Wellington, New Zealand, to Hong Kong – for their traditional burial in Guangdong, southern China – when it sank on October 27, 1902, after hitting a reef.

The startling discovery, made on May 22 this year, finally confirmed the presence of the miners’ remains, but not everyone shared the team’s sense of jubilation.