Nostalgia trip: three takes on the theme of celebrity

Oliver Stone, J. G. Ballard and Courtney Love are the authors of this week's variations on a theme: what it means to be famous

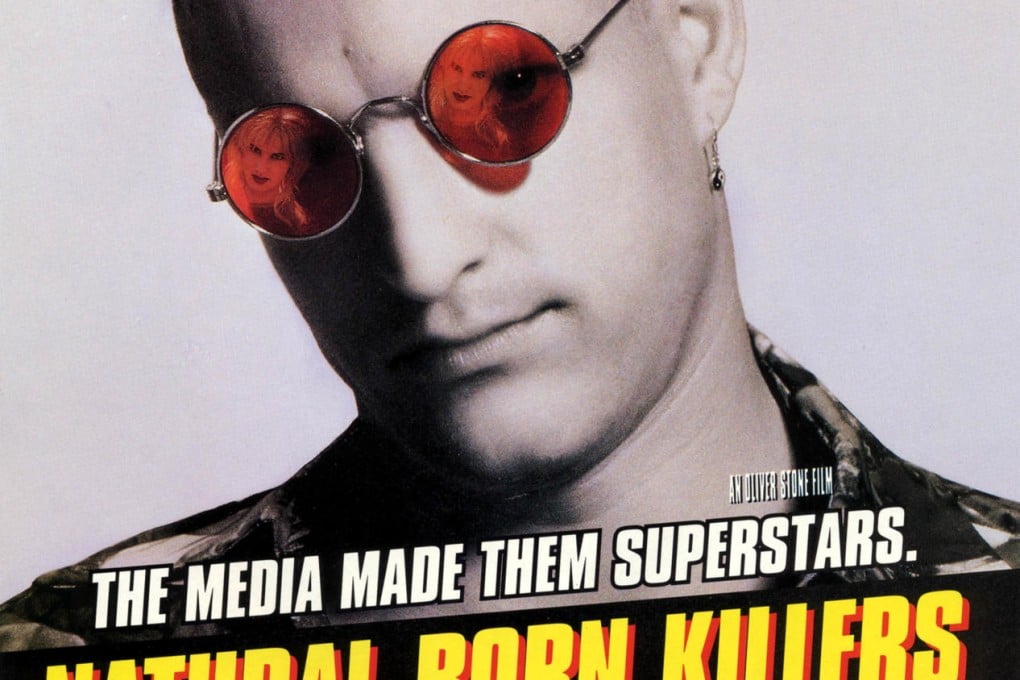

Film director Oliver Stone (Natural Born Killers, 1994), novelist J. G. Ballard (The Atrocity Exhibition, 1970), and singer Courtney Love's band Hole (Celebrity Skin, 1998) tackle the issue of celebrity.

Woody Harrelson, Juliette Lewis, Robert Downey Jnr

Oliver Stone

It's a horrible hybrid - a seedy mix of social media, reality TV and plain old hubris. All combined, the result is what we call "celebrity culture", a fascinating train wreck that shocks as much as it entertains. The film that predicted our voyeuristic tendencies all those decades ago was , a then-harangued and now strangely enthralling product of the 1990s.

Mickey (Woody Harrelson) and Mallory (Juliette Lewis) are two messed-up peas in a pod, victims of abuse who turn to serial killing as an outlet. The cops are on their trail, but so is a reality show camera crew, desperate to raise the duo's already sky-high reputation to new mass-media heights.

The film is undoubtedly a product of its slick crime flick era, but it's particularly noteworthy for its synthesis of two of the decade's most influential celebrity filmmaking voices: Quentin Tarantino and Oliver Stone. From the synopsis alone, it's easy to tell where one ends and the other begins. Tarantino had written the script as a means to break into Hollywood, a low-budget launch-pad that utilised his now-infamous gimmick of recycling grindhouse plots to further his own vision.