On paper, tale stands tall without the digital gizmos

Physical book of a series of apps for iPad proves it, too, can punch as it probes the role of language in a society, writes James Kidd

The Silent History

by Eli Horowitz, Matthew Derby and Kevin Moffett

FSG Originals

4 stars

The enhanced e-book - a digital text with multimedia extras - is one of the great unrealised dreams of publishing. DVDs with bonus footage - interviews, commentaries, deleted scenes, webisodes, bloopers - are not only de rigueur, but have enabled shows with relatively small but fanatical followings ( outside America, and almost any show on HBO) to become international treasures.

The book world has largely struggled to follow television's lead although there are notable exceptions. Faber & Faber's digital version of poet T.S. Eliot's is a high point. Various incarnations of the text, in manuscript form and easy-to-read print, are accompanied by commentaries, essays and readings by leading poets and actors.

Does language imprison or set us free? If something - a person, an object, an emotion, a mind - cannot be named, does it still exist (and if so, how)? Can there be community without communication?

A more recent and self-consciously integrated example is Richard House's , an anthology of four interlinked novels that blends conspiracies within conspiracies. House's narrative hybrid is matched by the material form of the story which embeds videos, maps and extraneous sections into the main story. These don't provide answers to House's many questions, but supplement the mind-bending universe that he has created.

Children's authors, of course, have been in the vanguard of those mixing word, image, music and something like gameplay. The masterpiece to date is arguably , which updates the puzzle book for an interactive, internet generation.

Written by the distinctly pseudonymous Gus Twintig, the story is a whodunit. Someone has stolen the numbers from a priceless clock, the Emerald Khroniker. According to legend the clock was built by a pirate named Friendly Jerome, who stole a number each from 12 civilisations' finest clocks. The clock was then stolen from the pirate and in a long line of robberies it is now owned by billionaire Bevel Ternky. The numbers have been stashed on each of the floors of his apartment building.

operates in ways that most fictional works simply can't. The really novel aspect of this novel is the way its virtual universe intersects with the real one. The clues are not just contained within the book but without: 12 emerald-studded numbers, made by jewellery designer Anna Sheffield, were hidden at highway rest stops in different states across the US - not much fun if you live in Hong Kong.

At the same time, there are narrative consolations from an older era. The story follows the trajectory of the classic crime novel: the miscreants are revealed on the final page. There are also plenty of vivid characters, most of whom have been inspired by circus archetypes. A clown called Jigsy Squonk lives on the seventh floor. Underneath him is Bert D'Grnp, a mime artist who has lost his unicycle.

The actual minds behind are Eli Horowitz, children's author Mac Barnett and illustrator Scott Teplin. The seeds that they planted have now matured into , a work intended for an adult audience. The link between the two is Horowitz, formerly the managing editor of Dave Eggers' revered McSweeney's publishing house.

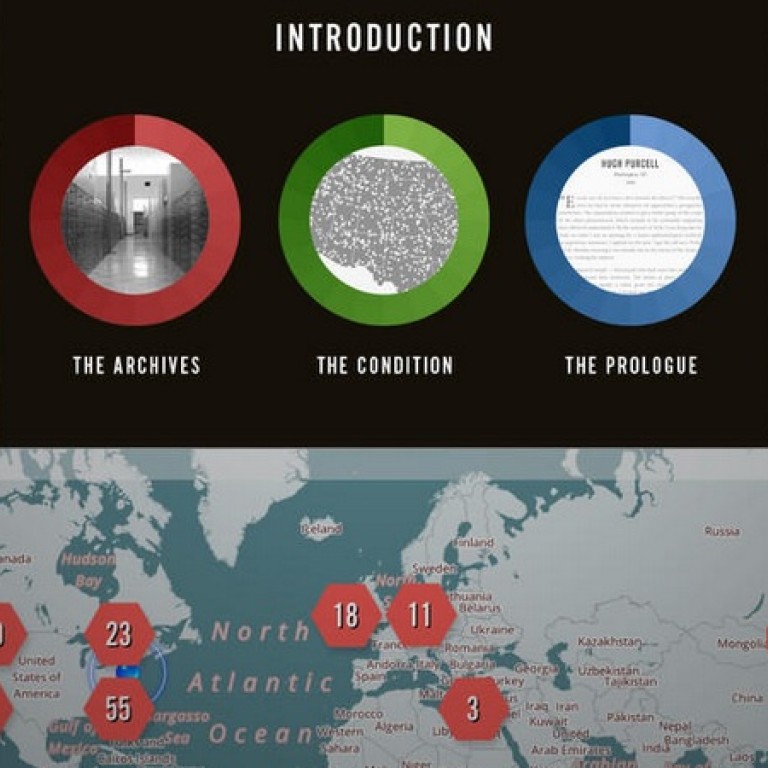

However, that ambitious mission statement and those "surprising skills" were more likely a reference to the digital version's rather fetching extra-literary features. The first printing - to use a suddenly obsolete term - extended the ideas and tech know-how that made such a fun pioneer.

The story was recounted through monologues divided between "Testimonials" and "Field Reports". Thanks to the wonders of 21st-century GPS, the "Field Reports" would respond if you happened to be in the location where one was set. Good news if you were in Chicago's O'Hare Airport or Kyrgyzstan. The plot was also shaped by time as well as place. The serialisation was moulded to follow an average week with story arcs developing over seven days.

This revolution in storytelling was entirely self-conscious. "E-books were unmistakably a lesser form," Horowitz said. In an attempt to correct this misconception he worked with two new writers: Kevin Moffett and Matthew Derby. McSweeney's digital wizard, Russell Quinn, created the app, which is effectively the "e-book" to which Horowitz referred.

The novel's high-concept premise proves to be brilliantly simple, and resounds to echoes of John Wyndham, Stephen King and J.G. Ballard. Locked in their own world, Silent children communicate only with other "Silents" through an intense form of face recognition. This world devoid of language forces an array of characters to interpret the silence in fairly consistent 1,500-word monologues.

A prologue informs us that these are records intended for posterity, but it is one of many smart twists that the urgency of the process is only revealed at the end.

This technique posits the children not as absences, but as mirrors revealing an individual's underlying character. We have the often desperate parents of Silent children, vacillating between fear and love, intimidation and sorrow, disappointment and longing.

Patti Kern, a cultish new-age earth mother, reads the children as embodying a long-lost innocence. A politician exploits this new constituency to make his name, but later backtracks when the populace turn against the Silent minority.

The plot's pivotal moment arrives with the invention of a "cure", which many Silents accept and, once it is made mandatory, a minority reject. The focus for the final volumes is a young family (Flora, Spencer and their Christ-like son, Theo) who flee the enforced corrective procedure. The beautifully modulated ebb and flow of these concluding sections sets the world of words and silence on a philosophical collision course.

Does language imprison or set us free? If something - a person, an object, an emotion, a mind - cannot be named, does it still exist (and if so, how)? Can there be community without communication?

Read on an old-fashioned paper page, these interrogations feel very last millennium - Shelley's pondered similar brain-teasers in 1821. Downloaded onto an iPad, they encourage similar meditations about contemporary culture. Are the authors anxious about an iGeneration locked in silent(ish) cyber-communion with one other? Or are they celebrating the next stage of youth culture rising out of the ashes of the old?

Exciting as the marriage between inventive narrative and ingenious technology undoubtedly is, it's hard to say it represents a profound advance on the reading experience. Readers always shape the narrative they have chosen, and not always in linear ways. My Heathcliff, for example, will not be the same as your Heathcliff, or Emily Bronte's Heathcliff for that matter.

When, where and why we read a novel also shapes the experience. read reluctantly at school as a compulsory text will feel very different when we pick it up eagerly in nostalgic middle age.

This is not intended as censure. Far from it. 's power feels simultaneously up-to-the-minute and old-fangled. The plot is driven by classic narrative virtues: chases, hints of the supernatural, dystopian thrills, intellectual mystery and cosmic jigsaw puzzle. The finale asks big questions that will absorb your thoughts for days.

"Let the unknown be the unknown. The things we need will reveal themselves in time." Indeed. Here is a novel at once fun, clever and humane that has the scope to outlast its hipper-than-thou origins.