Hong Kong’s first art-house film, Cecille Tong Shu-shuen’s The Arch, starring Crazy Rich Asians’ Lisa Lu Yan, was ahead of its time

- Cecille Tong Shu-shuen’s The Arch is an elegant psychological drama about a widow who has committed to receiving a stone ‘arch of chastity’

- With its roots in a folk tale, it may have also been Hong Kong’s first ‘independent’ film, having been fully funded by the director and her family

Martial arts films were all the rage in the late 1960s and 1970s, so it may come as a surprise to learn that the era also produced what is considered Hong Kong’s first art-house film.

The Arch, a Ming dynasty period piece directed by Cecille Tong Shu-shuen (sometimes known as Shu Shuen or Cecile Tang) in 1970, is an elegant psychological drama about a widow who has committed to receiving a stone “arch of chastity”. Although The Arch only played for three days on its original release in Hong Kong theatres, it went on to become a highly regarded work of cinema.

“The art-house look and ambitions of the The Arch set it aside from much of the commercial output of the early 1970s,” Roger Garcia, former director of the Hong Kong International Film Festival, tells the Post. “For a historical period film of the time, it lacks much of the requisite commercial action and sexual passion that were prevalent in contemporary local studio films.

“As one of Hong Kong cinema’s first women directors, Shu Shuen’s portrayal of a woman weighed down by social convention and the question of fate is more nuanced and ambiguous than those of male directors.”

Female heroines did appear in the ubiquitous martial arts films of the time, but feminine traits were generally ignored in favour of fighting skills which matched, or surpassed, those of the male antagonists, Garcia notes.

The Arch features Lisa Lu Yan as schoolteacher Madame Dong, a widow who has been chosen to receive a prestigious stone arch by local officials in honour of her decision to remain chaste after her husband’s death.

But when a visiting general (Roy Chiao Hung) takes up temporary residence in the schoolroom, romantic feelings develop between them. The nascent affair is complicated by Madame Dong’s flirtatious daughter Wei-ling (Hilda Chou Hsuan), who quickly falls in love with the general.

How Ringo Lam’s Full Alert blends action with premonition of 1997 handover

Partially out of loyalty to her daughter, and partially out of respect for her vow of chastity, Madame Dong arranges for her daughter to marry the general, and busies herself with housework and caring for her elderly mother. Her repressed sexuality leads to a fascinating Freudian montage in which she kills a cock.

Her ageing mother dies and her loyal servant, horrified by her self-induced misery, leaves the family home. Left alone, she watches the arch of chastity being built, a structure which looks like her tombstone.

The storyline of the The Arch has an interesting heritage. It began as a folk tale, and was then adapted into a short story by 20th century writer Lin Yutang.

According to an essay by critic Lau Shing-hong, the folk tale saw the widow seduced by a servant the night before she was to receive the arch, and this act led to her suicide. Lin’s short story changed the plot so that the widow willingly gave up the arch to have the affair, and married the servant in a happy ending.

“Shu Shuen’s treatment … turns it into a tragedy that depicts oppression by social systems and self-imposed restraints,” Lau wrote.

The Arch may have also been Hong Kong’s first “independent” film. The director, who was born in either Hong Kong or Yunnan province in southwest China and grew up in Hong Kong and Taiwan, was from a very wealthy family – her grandfather was reportedly a powerful Chinese warlord. (She was embarrassed about this, and dropped her family name, Tong, to disguise her lineage).

Her family sent her to study filmmaking in the US, where she wrote the script of The Arch. Returning to Hong Kong, she couldn’t get studio funding for the film, so she funded it with money from her family. She rented a disused soundstage from Cathay Studio at a cut-price rate and shot in black and white to save money.

As befits a recent film school graduate, Tong makes use of the full armoury of techniques available to the filmmaker – montage, freeze-frames, zooms and time-lapse photography are all on show. To add to the variety, she employed two cinematographers. Subrata Mitra, who had worked with Indian master director Satyajit Ray, shot the interiors while Qu Hexi shot outside.

“The film mixes a naturalistic style with a 1960s montage style that seeks to capture the inner emotional and psychological states of the character by overlaying images, shock insertions, and repeat cutting,” says Garcia. “It’s a style that derives elements from, for example, Roger Corman’s The Trip, and other psychedelic-inspired works.”

In his essay, Lau notes that the Freudian elements of the film, such as the murder of the cock to show the widow’s frustration, were popular elements of international cinema in the 1960s and 1970s. “Shu is deeply influenced by Western culture, especially existentialism and Freudian psychology, which prevailed in the 1960s,” he wrote.

Lu started her acting career in the US, and later became famous in Hong Kong. The Arch was the film that launched her career in the then British colony.

“Lisa Lu was in her mid-30s when The Arch was made,” Garcia says. “Her performance is superior in the film – she subtly conveys different nuances of emotion and repressed desire. Shu Shuen made sure Lu didn’t give an overwrought, melodramatic performance, which lesser actresses might have lapsed into, given that there isn’t much dialogue in the film.”

“The Arch was the hardest film I ever made,” Lu told this writer in an interview in 1999. “Shu Shuen had asked me to come to Hong Kong to be in the film. I really wanted to support this young director. She ran out of money, but I stuck with her right to the end.”

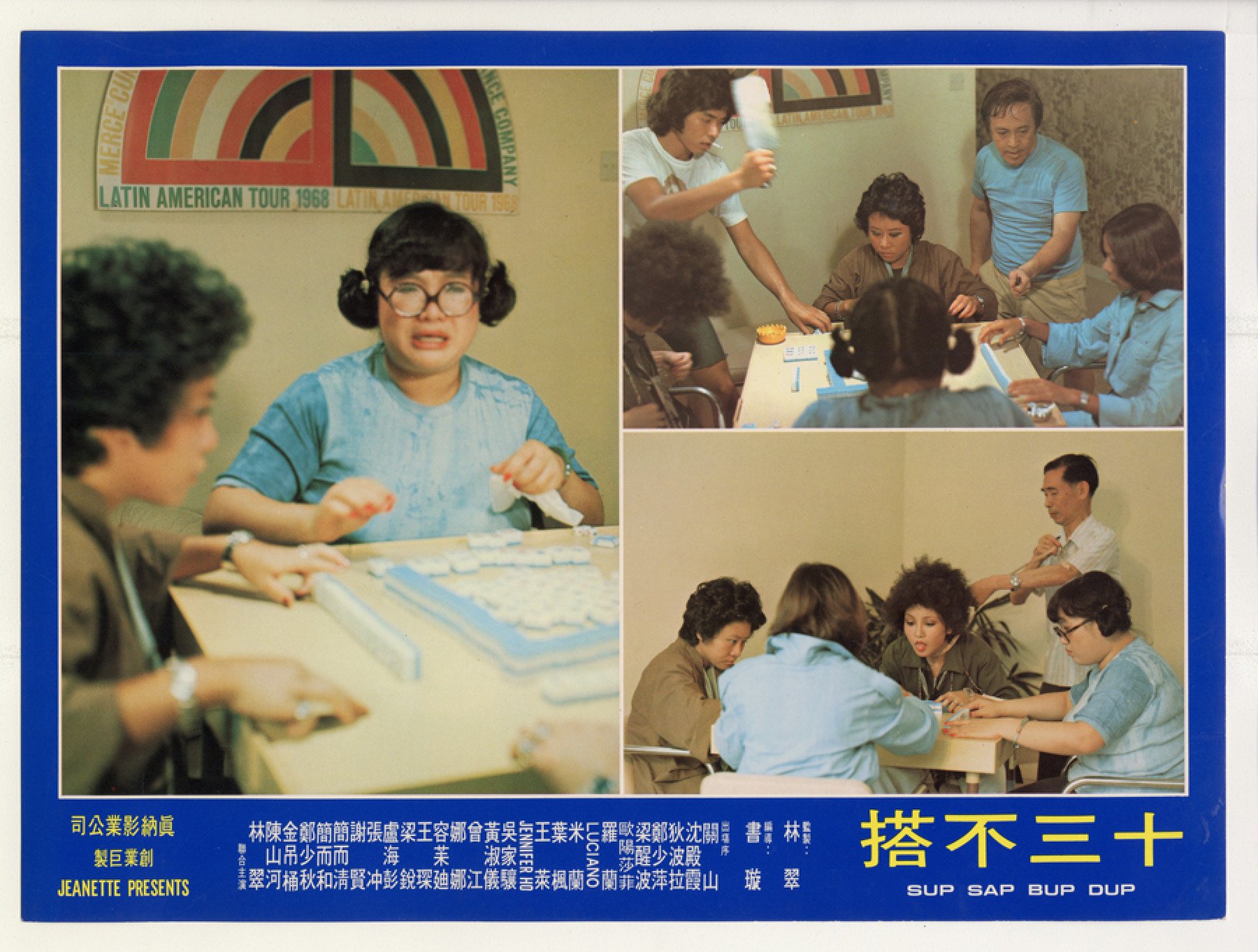

After The Arch, Tong made the equally acclaimed China Behind in 1974, a film about people escaping to Hong Kong from mainland during the Cultural Revolution. The film was banned in Hong Kong, although it did find a release years later, in 1987. Shu made two more films, Sup Sap Bup Dup and The Hong Kong Tycoon, before abandoning filmmaking and moving to the US.

“If Shu Shuen had made her appearance 10 years later, joining forces with the younger generation of filmmakers, her chances of making it commercially would have been much better,” wrote Lau. “Her debut was made before its time.”

In this regular feature series on the best of Hong Kong cinema, we examine the legacy of classic films, re-evaluate the careers of its greatest stars, and revisit some of the lesser-known aspects of the beloved industry.