Explainer | From One-Armed Swordsman to The Big Boss with Bruce Lee and Drunken Master with Jackie Chan, the films that built Hong Kong martial arts cinema

- King Hu’s Come Drink With Me brought artistry to martial arts cinema, Chang Cheh’s One-Armed Swordsman a year later added modern camera angles and gore

- Angela Mao paved a path for Bruce Lee to become a legend, Jackie Chan added comedy to the genre, and Jet Li and Tsui Hark updated it for the ‘90s generation

Hong Kong’s martial arts films have a long and distinguished history. We look at some classic films that contributed to the development of the kung fu cinema tradition.

Rooted in local culture

The films show Wong as an honourable individual steeped in Confucian values, and would only resort to violence when discussion, humility and compromise failed.

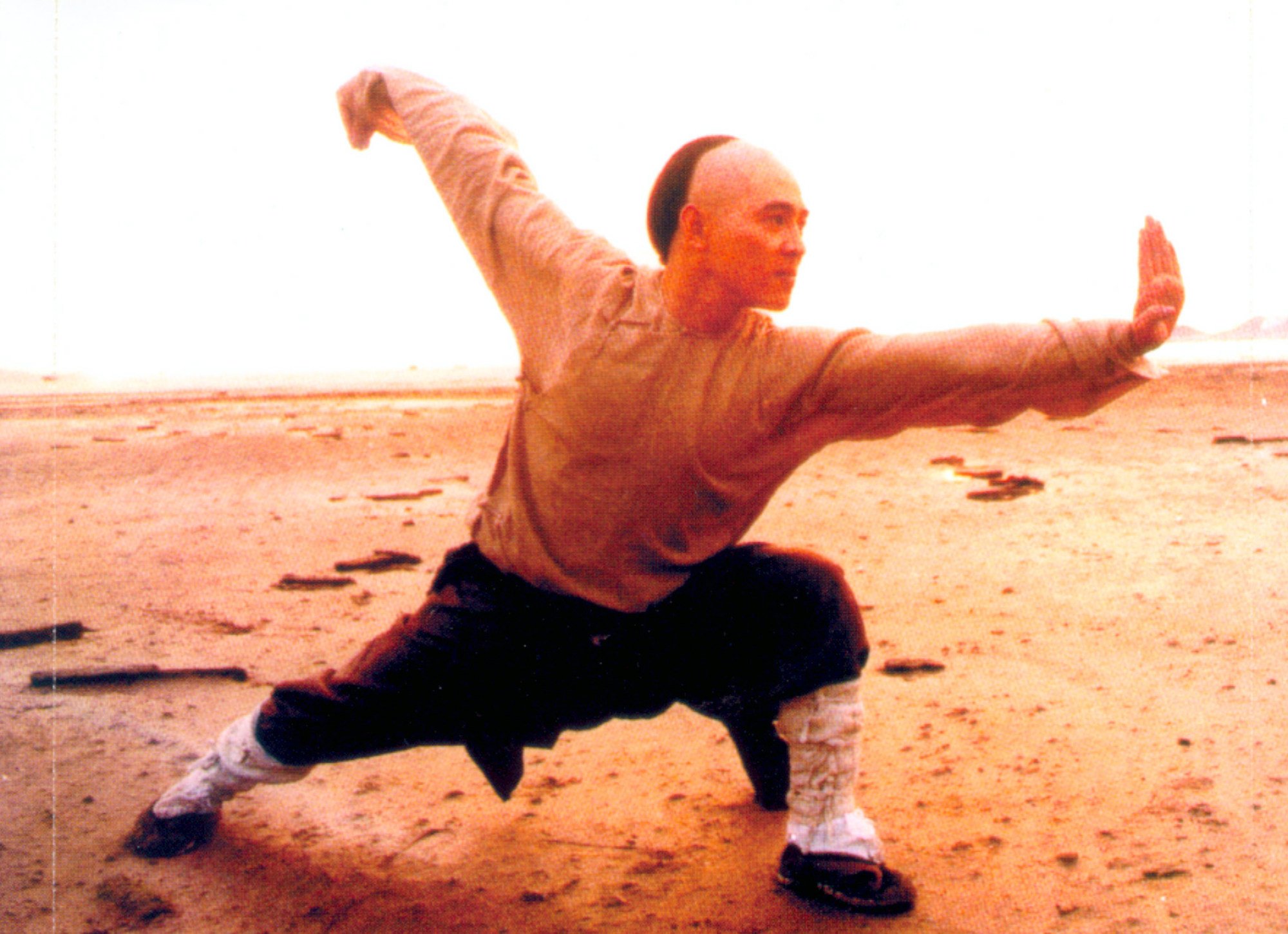

In spite of their ingrained Confucian values, the Wong Fei-hung films featured many fight scenes, most of which were based around the southern Chinese kung fu fighting style known as hung ga.

What Wong Kar-wai’s first two movies show about his style of filmmaking

They also espoused a kind of Cantonese nationalism which made them popular in Hong Kong, documenting Cantonese folklore and celebrating southern Chinese traditions such as the lion dance.

The stirrings of a new wave

In the early 1960s, filmmakers working in Cantonese – Shaw Brothers released its films in Mandarin Chinese – had raised the production values of sword-fighting films and made the action tougher.

Other exceptional films from the period include The Story of Sword Sabre parts 1 and 2, and Temple of the Red Lotus, which has “realistic swordplay sequences depicted with a fair amount of blood and gore”, according a critic at the time.

Bringing artistry to the genre

Hu said he knew nothing about martial arts, and adapted Beijing Opera techniques for the beautifully composed action sequences. He said this approach proved a “disaster” at the start of the shoot, and that the film was saved by Cheng’s lucid folk dance and jazz dance abilities.

Cheng quickly became a superstar.

The film that changed everything

Chang always dismissed his breakthrough film for not being “artistic”. Yet it stands as one of the prolific director’s most highly regarded movies.

Fighting with fists instead of swords

Sword-fighting films were still the big thing in 1970, so when Shaw Brothers’ biggest male star, Jimmy Wang Yu, went to studio head Run Run Shaw and asked to direct a kung fu film, his boss was not enthusiastic.

Firstly, actors acted and did not direct, and secondly, fist fighting films were not what audiences wanted to see.

“My idea for Chinese Boxer was karate against the iron fist of kung fu,” Wang told Grady Hendrix.

The Shaw Brothers directors whose films ran the gamut from wuxia to erotica

“I wrote a script, but Run Run Shaw said, ‘No, you have no experience – you’re a big star, don’t try and be a movie director.’ I told Run Run to let me do it, or I would quit. He did, and it broke box office records. Shaw gave me a HK$200 bonus.”

Girl power!

The latter was mind-bogglingly renamed Deep Thrust to capitalise on the popularity of the mainstream porn film Deep Throat, even though there were no sex scenes in Mao’s films.

Mao is still revered by martial arts film fans in the US.

The Man, the Myth, the Legend

Lee broke some boards on the popular show Enjoy Yourself Tonight, and was quickly snapped up by Golden Harvest. The Big Boss followed, and quickly broke box office records. The rest is history, myth and legend in equal parts.

Just for laughs

Ng said the idea for the film arose during a visit to some Taiwanese film distributors: “Everybody was drunk and playing guessing games, but me and Yuen were sober and we got to taking about how they looked like they were doing kung fu in a drunken fashion.”

Drunken Master made Jackie Chan a superstar.

Back to their roots

“I got to thinking that Chinese history in the early part of the [20th] century was a very turbulent period, so why would Wong remain a placid traditionalist?” Tsui said. “That was the engine that drove the picture.”

Tsui’s films single-handedly started the martial arts film boom of the early 1990s.

In this regular feature series on the best of Hong Kong cinema, we examine the legacy of classic films, re-evaluate the careers of its greatest stars, and revisit some of the lesser-known aspects of the beloved industry.