A Hong Kong filmmaking masterclass from Wong Kar-wai, for whom ‘story is not important’, Wong Jing, for whom a director ‘is like a chef’, Johnnie To and more

- To make a film in the Hong Kong style, start with what directors have said about their art. Wong Kar-wai’s focus is on characters, Wong Jing’s on his audience

- Herman Yau makes the films he wants even if film-goers don’t want them. When Johnnie To injects events from real life into his characters, it’s OK if they fail

Want to make films in the Hong Kong style?

Read on for an unofficial masterclass in Hong Kong filmmaking, compiled from interviews with some of the city’s best known directors over the years.

“I do not make up my stories up in isolation. As a story develops, the personality of the characters cannot be separated from your own preferences. The story can be developed in various ways, but it originates from you.

“It is like, based on my own understanding, I think these characters would react in a certain way. My films are not about stories. I develop plots from the characters’ personalities. I believe the story is not important, but the characters are.”

“I’ve rarely put scenes of real life in my films before, but in Loving You I did. Like the minute-long scene in which Lau Ching-wan fell asleep in his car – I experienced that in real life, and I know exactly how one feels in a situation like that.

“I just tried to put pieces of things that really happen in society together in one character. It doesn’t matter if he regrets his actions or not, it doesn’t matter if he does the wrong thing the whole way to the end, because these things happen again and again in Hong Kong’s everyday life.”

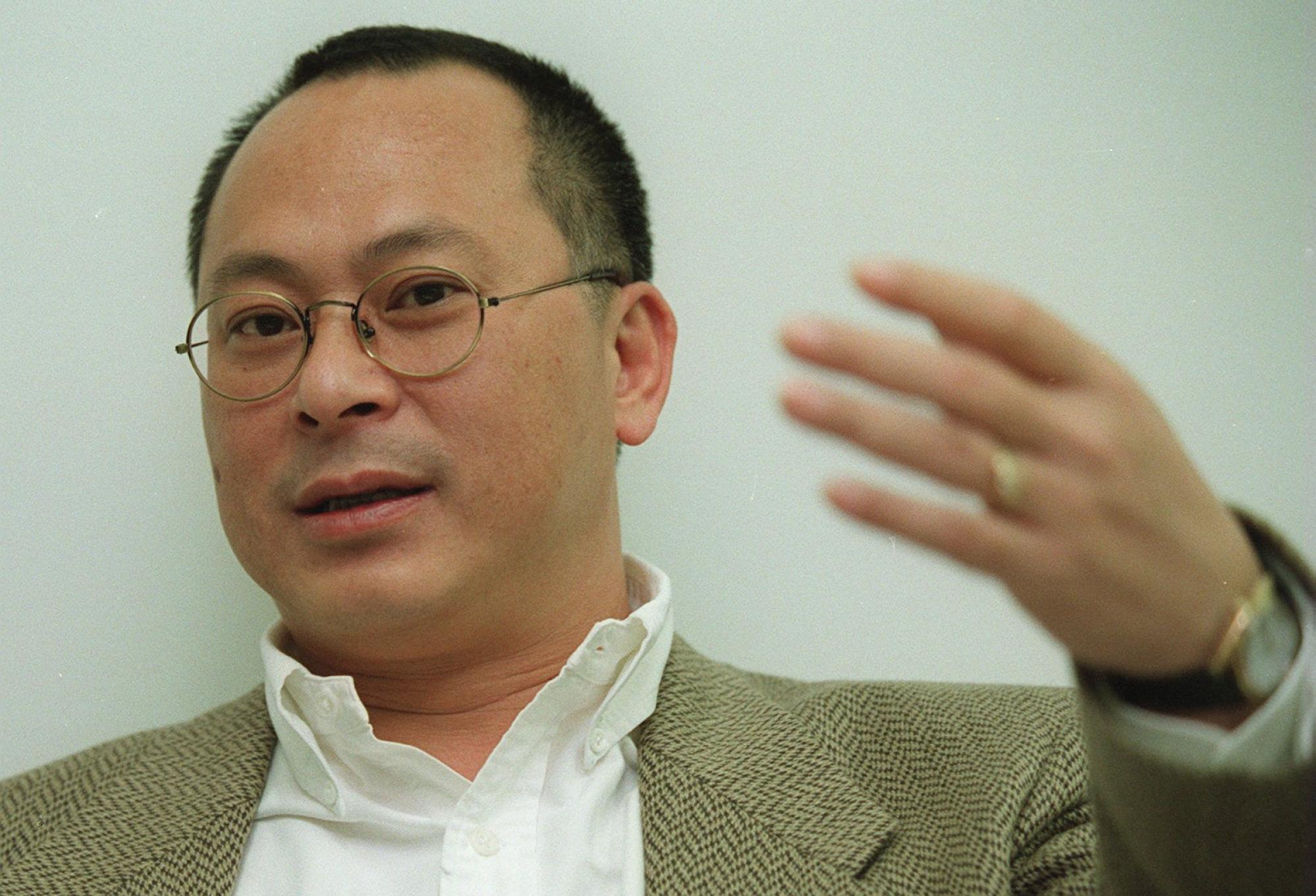

“To me, a director is like a chef. I make the dishes that the audience wants to eat. Most director loves their movies, but I never fall in love with mine.

“When they are editing, it’s like they are making love to a film. They hate to finish it. But I don’t. I always like to edit my movies very fast. I always try to give the audience what they want. That’s the way I have done it for the last 20 years.”

Yim Ho, after directing The Sun Has Ears in 1995, on filmmaking as a voyage of self-discovery:

“I feel that the filmmaking process is also a process of learning about myself – it’s kind of like swimming in a mental way, kind of roaming around and seeing what you find.

“A film reflects the mental state that I am in when I am making it. A film reflects my way of looking at life.

“With The Sun Has Ears, I didn’t actually realise that I was making a film to understand myself. It wasn’t until after I’d finished it, when I was talking about it, that I realised I had solved some personal problems, and learned something about myself.”

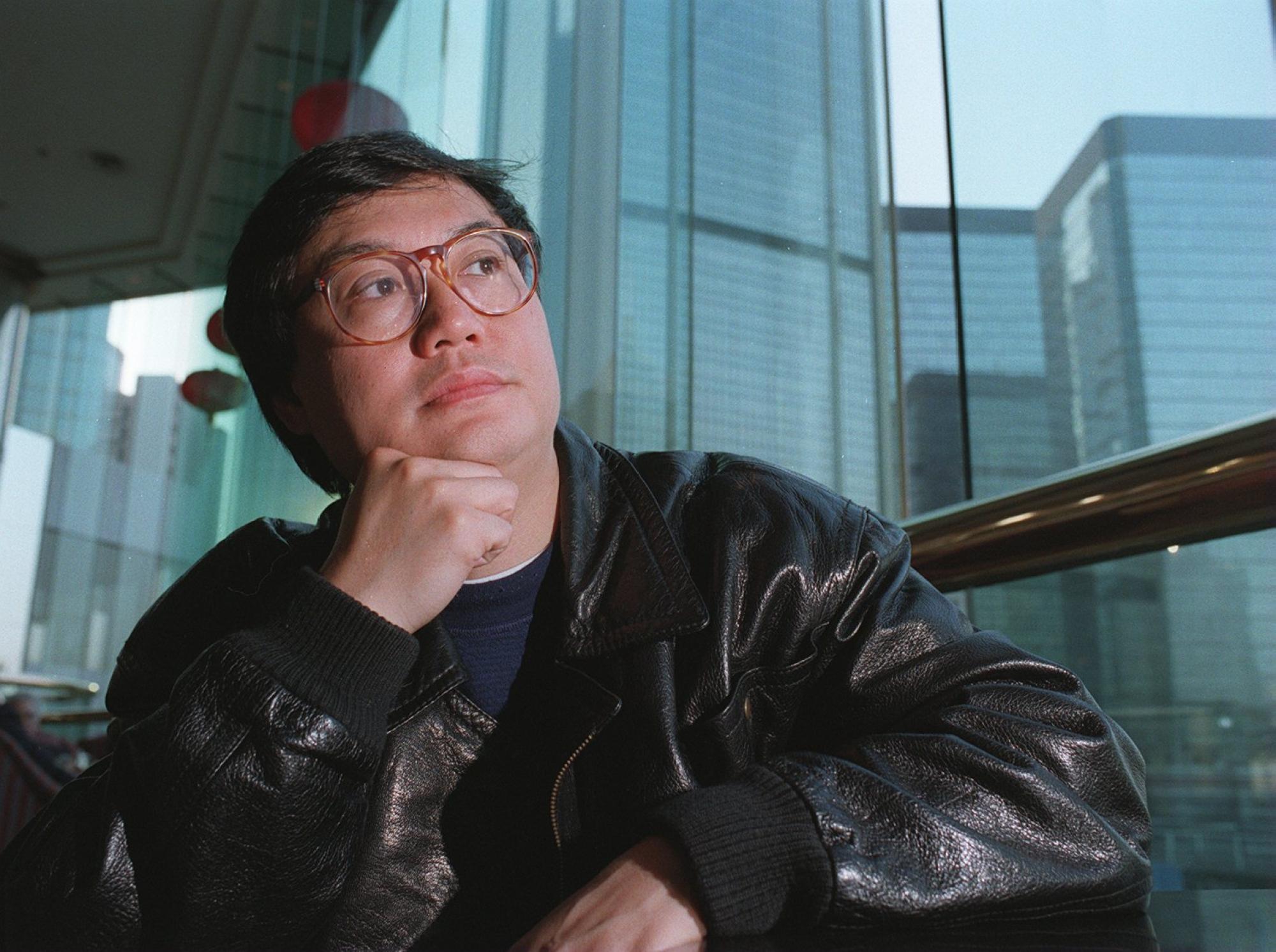

“For a number of years I have been trying to make a film that would both allow me to express myself and entertain an audience. Looking back at my work, I don’t think I’ve ever succeeded.

“The Untold Story was criticised as reckless speculation, regrettably by a film critic whose opinions I highly respect. Ebola Syndrome had a similar fate in 1996. Apple Daily gave it one point out of a possible 33.

“Despite all of these negative comments, at least I am glad to say that I have pleased myself.”

“I love hardware. I love models, and when I was young, I used to spend hours making those Airfix (a popular scale-model brand in the 1960s and 1970s) models you could get.

“I got the little Airfix soldiers, too, and fought battles with them. I think that my storytelling techniques and my choreography originate in the battles that I played out at home with those Airfix soldiers.

“I learned a lot about guns, planes and war from them, and eventually became a pacifist. Actually, I still do make models, and I have a lot of them!”

“It’s a matter of give and take. If you don’t ask for the social advantages of being a woman, you won’t get the disadvantages.

“Filmmaking is an extremely competitive business. Movie companies seldom look at gender, or outward appearance; they look at talent.

“Women directors are not even an issue now. You don’t hear people saying, ‘Ah, there’s an interesting director – look what a woman can do,’ any more.”

“In those days [working at Cinema City with Tsui Hark in the early 1980s] a movie had to be 90 minutes long – it couldn’t go beyond that. If it was 90 minutes, you could get five shows a day [in the cinema], but if it was 100 minutes, you couldn’t get all five shows in.

“When we shot on film, each reel was basically 1,000 feet (300 metres), which makes nine reels for a 90-minute feature. When we wrote the story, we represented each reel with an empty page. So we had nine empty pages.

“We figured out what the story was, and got the start, middle, end, and the resolution down. Then we filled in the blanks. It was very smart.”

Joe Ma Wai-ho, talking to Tim Youngs in 2002, on the differences between directing and producing:

“My work as a director and producer is quite different.

“When I direct, I look deep into my heart – creatively, I do what I want to do. Most of my films are entertaining youth pictures.

“But when I’m producing, I try and find directors who have their own style, their own personality. That is my number one aim as a producer.

“Creatively, I don’t try to change their style and I don’t change their stories. I just try to encourage them. I want them to make movies that they are proud of.”

“When I first became a director, on Against All Odds, I hired a cameraman. But when we saw the rushes, it wasn’t at all what I wanted. I knew what I wanted, but I couldn’t describe it, so I took over the camera myself. It’s faster as there’s no need to talk!

“I don’t want to be telling someone what to do all the time. So I shoot all my films myself. It’s hard work, but it’s better.”

In this regular feature series on the best of Hong Kong cinema, we examine the legacy of classic films, re-evaluate the careers of its greatest stars, and revisit some of the lesser-known aspects of the beloved industry.