Being on TV show inspires Hong Kong high fliers to help the city's poor

In the third of a four-part series on poverty, Elaine Yau looks at how several high-profile Hongkongers were inspired to create a range of projects to help the poor after participating in a reality TV show

When you're down and out, getting a hot dinner can seem like a pipe dream. But next year, some of the city's less fortunate citizens will be able to enjoy a restaurant meal paid for by anonymous benefactors when an online platform is launched to link restaurateurs with charitable citizens ready to subsidise the food.

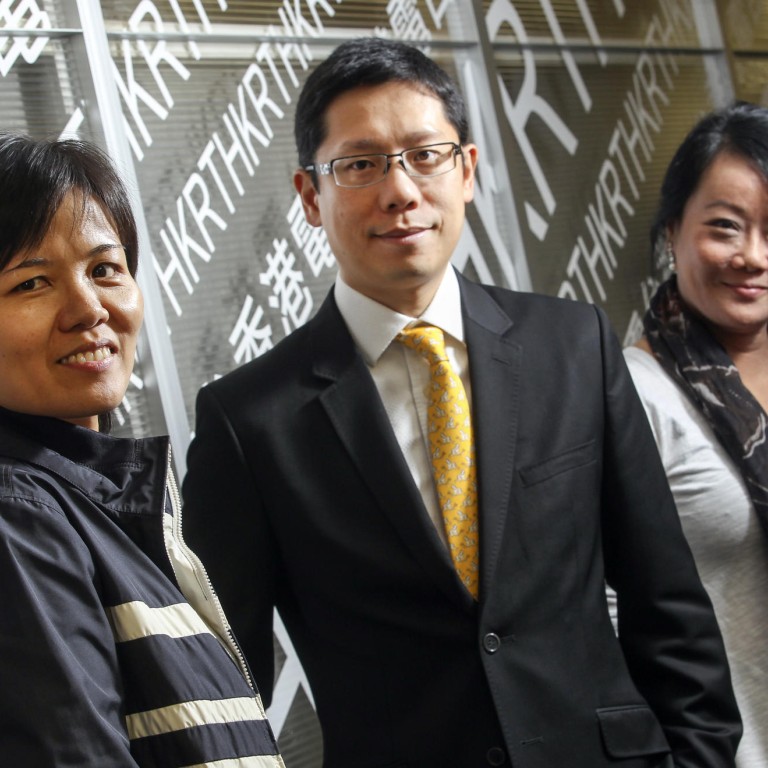

Simon Wong Kit-lung, executive director of Chinese restaurant chain LHGroup, came up with the idea after taking part in , RTHK's television series on poverty. The latest instalment of the biennial series has yielded a range of creative anti-poverty projects, including one that sees architects visit poor families to offer tips on how to make the most of discarded furniture and the space in their cramped homes.

There are many compassionate Hongkongers out there. They just don't know where to go if they want to help

When the public broadcaster started the series in 2009, it departed from the usual news feature format by adopting a reality approach. Producers recruited high-profile people, such as CEOs and models, to spend a few days living like the people they were trying to help in order to give the audience a better appreciation of the plight of these families.

Hopefully , the official poverty line, set for the first time in October, will help officials draw up more comprehensive strategies to help the poor. Still, the uncomfortable truths revealed through the RTHK series continue to have a salutary effect on participants and audiences alike.

The executive producer of the programme, Doris Wong Lok-har, is gratified that the first two instalments succeeded in drawing the attention of Hongkongers, many of whom had become accustomed to the long-standing social problems related to poverty. (New People's Party legislator Michael Tien Puk-sun, who founded the G2000 clothing chain, created quite a buzz when he spent time working as street cleaner for the 2011 instalment.)

"Getting rich people to live [like the underclass] enables viewers to understand the details of what poverty means and the desperation it entails. Instead of being just a concept, poverty means day-to-day living difficulties with no way out," Wong says.

Johnny Chan Kwong-ming, chairman of investment company Titan Works, took part in the second instalment when he spent four days among the elderly poor scavenging scrap paper and cleaning public toilets to earn money.

"I lived in a caged home along with other poor elderly. What struck me most was their dignity," says Chan. "Every elderly person there told me they didn't need government handouts. They just want to be self-sufficient. Having worked their whole lives, they deserve our respect even though they are just scraping by in their twilight years."

For the latest instalment, which ran last month, Wong's team went one step further by getting professionals with expertise in relevant fields to live with the poor and come up with anti-poverty proposals at the end of filming. Such a proactive approach is unusual in public affairs programmes, but it was certainly timely. After all, the city's wealth gap, using the Gini coefficient as an indicator, reached its widest in 40 years last year.

"While the third instalment didn't bring as much media coverage, it has led to projects that involve follow-up work. Previously, the TV crew and participants just shot the programme and disbanded. But this time there's continuity," Wong says.

"Together with [star tutor] Richard Eng, viewers saw how underprivileged kids can be put at a huge disadvantage because of their poor English proficiency … Eng initially thought that university admission could be a way for them to break out of cross-generational poverty, but their poor command of English is [a hurdle]," she says. "At the end of the programme, he came up with a tutorial venture to help poor students cope with the public exam. This can bring them closer to the goal of university admission. He's looking for a venue now and classes will commence early next year."

Similarly, Simon Wong's experience in the food business (his empire of more than 30 restaurants generates a turnover of HK$1 billion annually), and as a member of the minimum wage and poverty commissions, make him a fitting candidate for the show.

"Serving on so many public bodies, I feel I have the responsibility to know about the real conditions in society," he says. "But my identity is quite sensitive. The business community might wonder whether I will support setting a higher minimum wage after my participation in the programme, but … it is a complex issue. If you increase the minimum wage, you will deal a blow to small business owners, who are just a step up from being among the poor. We need to strike a balance."

However, Wong concedes his encounters in the series have changed his outlook. He enjoyed a privileged upbringing and inherited his business from his father, so the four days he spent as working in a supermarket and as a kitchen hand were a revelation.

Earning a mere HK$50 a day, he could only afford to live in a windowless cubicle.

"The flat was subdivided into five cubicles," he says. "It had no cupboard, fan or TV. People living in such places can't even get a good rest after an exhausting day. Luckily, on the day I arrived I ran into a woman who lent me a fan. It was my birthday that day. The fan was the best birthday present ever; I could sleep with a bit of ventilation."

So when he recently spotted some of his restaurant staff sleeping in a corner within sight of patrons, Wong was a lot more tolerant.

"In the past, I would definitely [have been very angry]. But now I am more understanding of their difficulties and have set aside a corner, out of customers view, for them to take naps," he says.

"My mindset before was simply of a businessman; I had to maximise profits, otherwise the business would fold eventually," he says. "Although I didn't become a communist after the four days [of filming], I have become more compassionate towards my staff ... as I realise the plight they are in."

One day during his time on the show, he was walking home to save on transport expenses when he saw a restaurant in Mong Kok giving out what was called suspended rice - boxed meals that had been paid for by others. "I kept a stiff upper lip and went inside the restaurant to ask for [a free meal]," he recalls. "It turned out there are around 10 restaurants in Hong Kong operating such services."

It was this experience combined with his struggle to subsist on a daily wage of HK$50 that led to his idea of setting up a platform to link compassionate restaurateurs and citizens.

"With my expertise in catering, I thought of setting up a platform that restaurants can join to sell meals at a discount to citizens who want to give a helping hand. After the TV programme aired, I received calls from 100 people asking where they could pay for those meals in advance. There are many compassionate Hongkongers out there. They just don't know where to go if they want to help."

Jennifer Liu Wai-fun, a former architect whose family established the Liu Chong Hing Bank and who now heads the Caffe Habitu chain, found the nights she spent with a family in a hut built on top of an industrial building equally illuminating.

"The people who live there don't have a permanent abode. They don't know when the next raid targeting illegal structures will hit them," she says. "They live in constant fear as they might have to move out at any time. My neighbours there did not dare to plan for anything, like whether to have baby, because their future is in perpetual doubt."

As filming wound up, Liu gathered a group of architect friends to visit families to try and help them maximise their cramped quarters. She aims to continue the exercise through the coming year.

"The get-togethers are held once a month. Six architects will be involved every time," Liu says. "Despite the constraints of a tiny cubicle flat, architects can create better living spaces through better light and furnishing arrangements. In Japan, capsule hotels can still look sleek and hygienic although they are not much larger than a shoebox."

For the last episode of the show, seven of the 14 participants gathered over a meal to discuss their experiences and ideas for further anti-poverty schemes. While 14 people cannot change the world, Simon Wong says they hope their experience can encourage the public to pay more attention to the poor and do what they can to alleviate their plight.

"The little work that each of us does, when combined, can have great power to make a difference to poor people's lives."