Cambodian women who flouted archaic rules are now role models promoting gender equality

- Generations of rural Cambodian girls were taught traditional rules for how to be a ‘proper woman’, dutiful wife and home maker

- Some rebelled, determined to carve their own paths

Thavry Thon smiles as she recalls sitting in her classroom at age 11 reciting verses from the Chbab Srey. “I still remember today how to sing those songs,” she says.

Born in Cambodia on Koh Ksach Tunlea, a small island 40km south of Phnom Penh, like most her peers Thon, now 28, was raised in a traditional rural community. According to societal norms, Thon’s life was laid out for her. She would attend school before dropping out in her mid-teens, secure a menial job, marry, have children and look after the home.

No, not Songkran – that other water festival, in Cambodia

Throughout this the Chbab Srey was integral for her, as it provides a code of conduct for all Cambodian women – for men there is the Chbab Proh, which is a much shorter rule book.

“I had never travelled out of my hometown, so when I was taught the Chbab Srey in school I knew no different,” she says. “All I’d see looking around is what it teaches is true – women are supposed to be good housewives and must act accordingly to be a proper woman. I remember when I left my small world, thinking about some of the verses and thinking: this is not right.”

Written in the mid-19th century, the text is packed with poems that prescribe how a woman should behave. Verses dictate a wife should serve her husband, remain quiet and submissive, not walk quickly and know their place in the home. It also states education is more important for men than women.

“Don’t walk so fast that your skirt makes a sound,” it instructs. “Don’t sit on the stairs in front of your house. People will think you’re waiting for a boy. Don’t speak loudly. Don’t laugh loudly.” Elsewhere, wives are told to “remember to serve your husband, don’t make him unsatisfied”, “be respectful”, and “no matter what your husband did wrong … be patient”.

It is also heavily littered with proverbs, such as, “Men are gold and women are white cloth”, and “women cannot dive deep or go far”.

Don’t walk so fast that your skirt makes a sound. Don’t sit on the stairs in front of your house. People will think you’re waiting for a boy. Don’t speak loudly. Don’t laugh loudly

In contrast, the much more succinct Chbab Proh teaches men to be hard-working, productive and proactive. To “walk as dragons” and forge their own independent path in life. Despite the text being removed from the national curriculum in 2007, it is still informally taught in many schools, especially in rural provinces.

“The ideas in it, if not the graphic detail, still very much inform what teachers tell students in their lessons about morality, especially older teachers and those in the countryside,” says Menno de Block, who co-authored “Diving Deep, Going Far”. Released earlier this year, it is the result of interviews with 25 Cambodian women who have battled adversity to get where they are today.

“Most of the text may be gone from the curriculum, but much of the thinking is still there, in school and society at large,” Menno de Block says.

However, the tide is turning, and although the Chbab Srey’s message is deeply ingrained in society, women are starting to fight for their freedom and carve their own paths. In a country where tradition still runs strong, this comes with challenges.

“There were a lot of people, including my father, who told me not to laugh loudly,” says Kounila Keo. The 30-year-old, who was named one of Forbes “Under 30s Game Changers” in 2017, adds she is fortunate to have had a strong female figure in the form of her mother.

“It was my mother who told him to let me. When I walked noisily and fast, people criticised me for that. I thought, come on this is ridiculous.”

Even today, Keo is often asked why she does not behave like a “Cambodian woman”. “That phrase, ‘Cambodian woman’, comes with stereotypes attached to it,” says Keo, who made a name for herself as one of the country’s first bloggers and digital pioneers. She is now managing director of public relations and communications company Redhill Asia (Cambodia and Indochina).

“People think I’m too strong. I choose my life because I want it. Don’t keep telling me I should get married and have babies.”

Thon also faced prejudice growing up, despite having supportive parents. From the of six she harboured dreams of being a writer and painter, but relatives and older villagers ridiculed her ambition.

“They didn’t believe higher education would change my life,” she recalls. “All they saw was short-term investment. Quit school early and work in a garment factory for US$100 a month. Even my grandfather said this. My parents fought with him to keep me in school.”

From the pristine beaches of Malaysia to the Killing Fields of Cambodia

Thon’s parents also faced criticism from fellow villagers for investing in their daughter’s future. Determined to give their children the opportunities they were denied, her parents sold gold, cattle and land to finance Thon and her siblings’ education. In October 2007, she moved to Phnom Penh with a friend to study. She chose computer technology and was the only girl in class.

“Moving to Phnom Penh was a huge culture shock,” she says. “In my hometown we all know each other, and I often felt isolated because I was a shy girl, fresh from the village. I was surrounded by boys and it was a barrier for me on how to interact with them.”

Headstrong Vannary San, 38, spent six months lobbying her parents to allow her to move from her remote village in Kampong Chhnang to Phnom Penh in 1997.

“They were worried about me being a girl and being so far from home,” she says, adding her family became victims of village gossip after her departure. “They’d say, ‘Why does this parent allow their daughter to go to the city? She’ll become a city girl. She will have so many boyfriends’. There were so many rumours. I was seen as a bad girl.”

Determined to prove her critics wrong, the mother-of-three secured a full-time job, juggling work and studies – later having children. “It was long days and hard work,” she recalls. “It took me seven years to finish my degree. I was a wife, a mother, a student and had a full-time job.”

In 2003, with one sewing machine and a tailor, San launched Lotus Silk, a social enterprise that produces ethical silk, clothing and accessories. Her tireless work training and employing poor villagers to produce the high-quality silk Cambodia was once famous for, and her work for gender equality, have earned her a clutch of awards, including one for Women’s Creativity in Rural Life and Asean’s outstanding woman entrepreneur.

“The older generation – the same age as my parents – who talked about me have stopped now,” San says. “They are glad to have a kid from their hometown who has done this or that. Now when they see my parents, they say they’re happy and talk about what the daughter of Mr Kosal is doing.”

The former Khmer Rouge cadres who turned to God for salvation

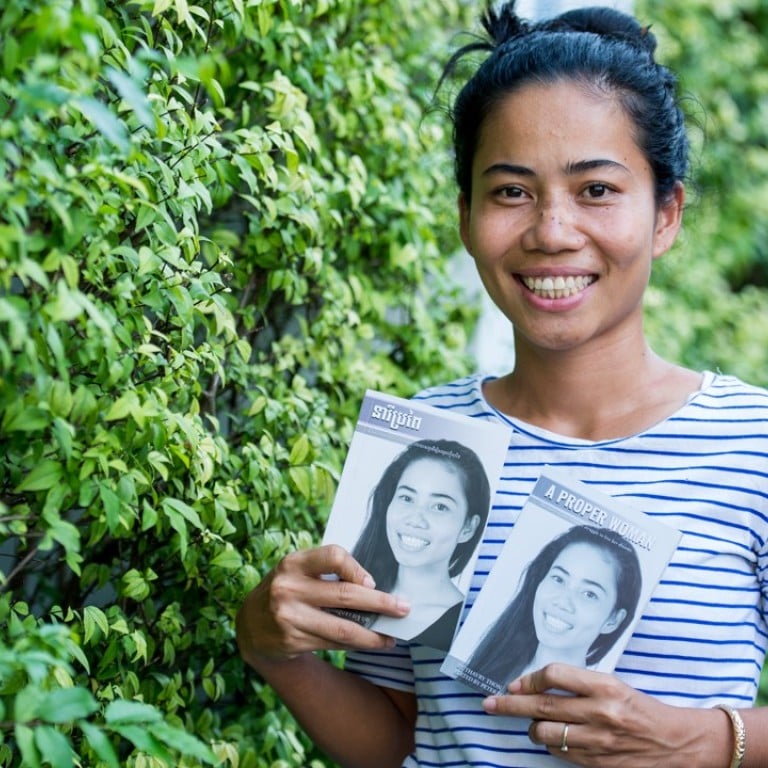

Thon has also been able to prove the education her parents invested in has paid off. In 2017 she released her fourth novel, A Proper Woman, which chronicles the struggles of growing up as a female through the eyes of three generations – herself, her mother and her grandmother.

Living during an age when the Chbab Srey was strictly adhered to, her grandmother followed the life that was expected of her. Her mother’s attempts at rebellion were halted by civil war and the Khmer Rouge reign from 1975 to 1979.

The gender equality activist hopes her book will inspire other young Cambodian women to chase their dreams. Thon held a series of fundraising events that enabled her to donate 2,500 copies of her book to rural schools. “I want girls to feel inspired, that they are not alone in this journey and to keep going,” she says.

They were worried about me being a girl and being so far from home

As an increasing number of inspirational female role models emerge in modern Cambodia, and education becomes more accessible, attitudes are shifting and the Chbab Srey is slowly being confined to the history books.

“When a generation starts to think critically about what is happening to them, you start to see people challenging that,” says Menno de Block. “The key here is in the critical thinking, and there are many factors that contribute to a rise in that over the past 10 to 15 years: better access to education, more exposure to alternative ways of thinking, volunteering and experiences abroad.”

With change teetering on the horizon, there is hope that instead of the out-of-date rules taught in the Chbab Srey, gender equality will be delivered both in the classrooms and at home.

“This is an issue for society as a whole,” says Keo. “A female’s identity shouldn’t be attached to a man. You can still love someone, be with someone, be someone’s wife and be an individual.”