Chinese girls adopted by US and Dutch families find closure after reunion with birth parents

- Linde Welberg and Lianna Fogg were given up for adoption in China because of the country’s one-child policy – but vowed to find their biological parents

- Both felt pangs of separation, torn between two worlds, but found closure and happiness when they met their birth families

Growing up in the Netherlands, Linde Welberg knew she had the most loving parents a child could ask for. Yet she had always felt something was missing from her life. Long before her father, Wim, and mother, Mieke, told her she was adopted, she instinctively knew it.

“I felt a part of me was missing. I feared my birth parents might be dead. I cried to see them, asking if they’d left a note, phone number or address,” she says.

On the other side of the Atlantic, in the US city of Philadelphia, Lianna Fogg was going through similar turmoil. “I shared the same dream of every adoptee,” Fogg says. “Not just to find my birth parents, but to be accepted by them.”

The two young women have never met, but share a common experience. Put up for adoption as a consequence of China’s now-abandoned one-child policy, both have lived lives far removed from the circumstances of their birth. Each has felt pangs of separation and loss, torn between two worlds, despite being raised in loving homes.

Both have bridged the divide between them and their lost families, however, through dogged determination and the power of social media. Last year, the two young women visited China for emotional reunions which gave them a sense of closure.

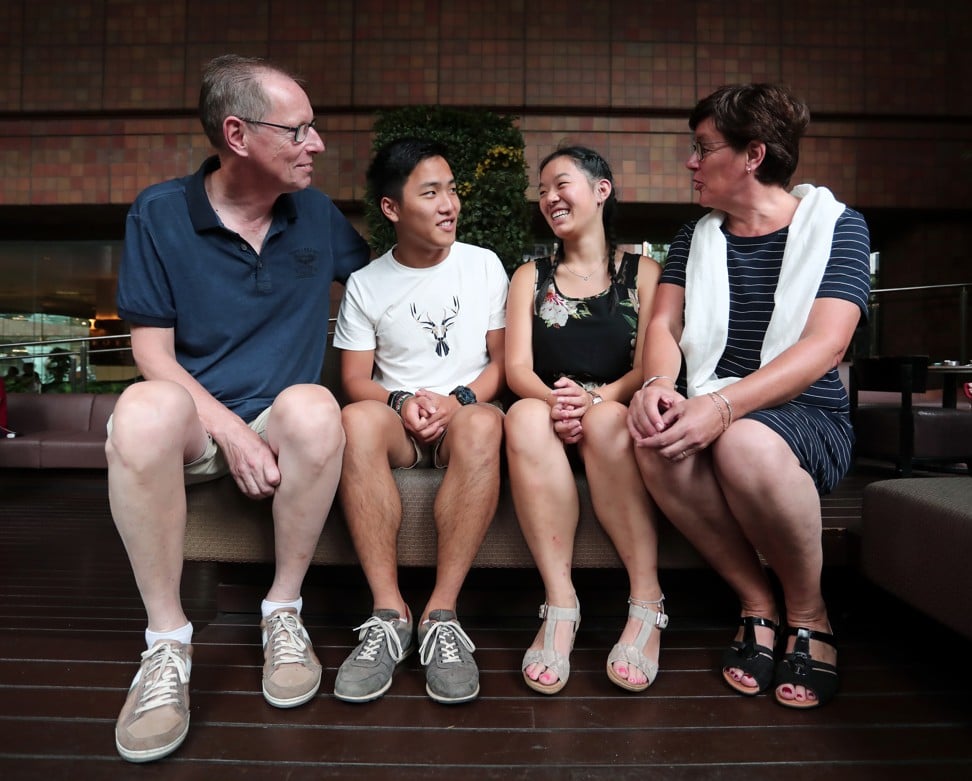

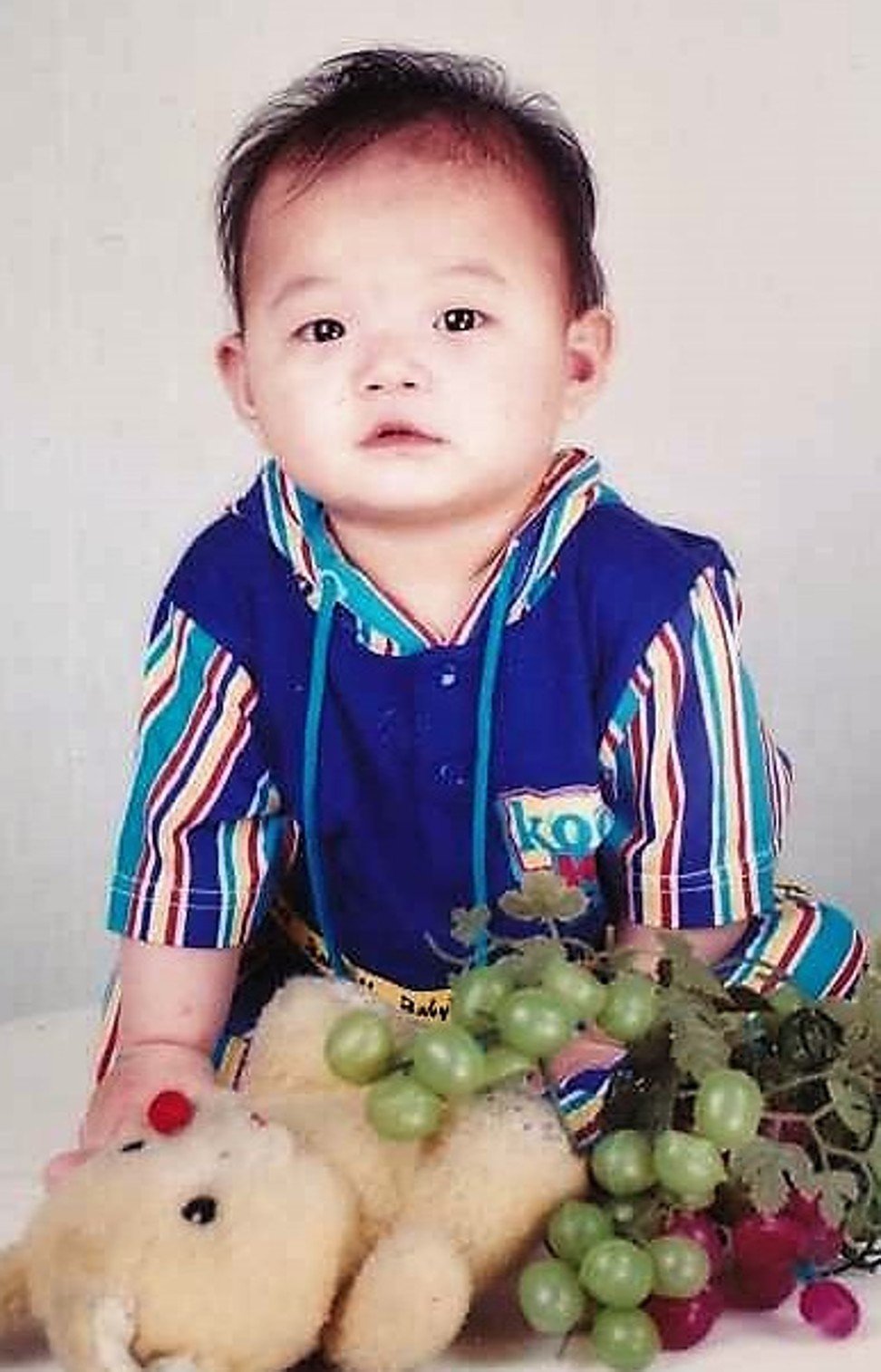

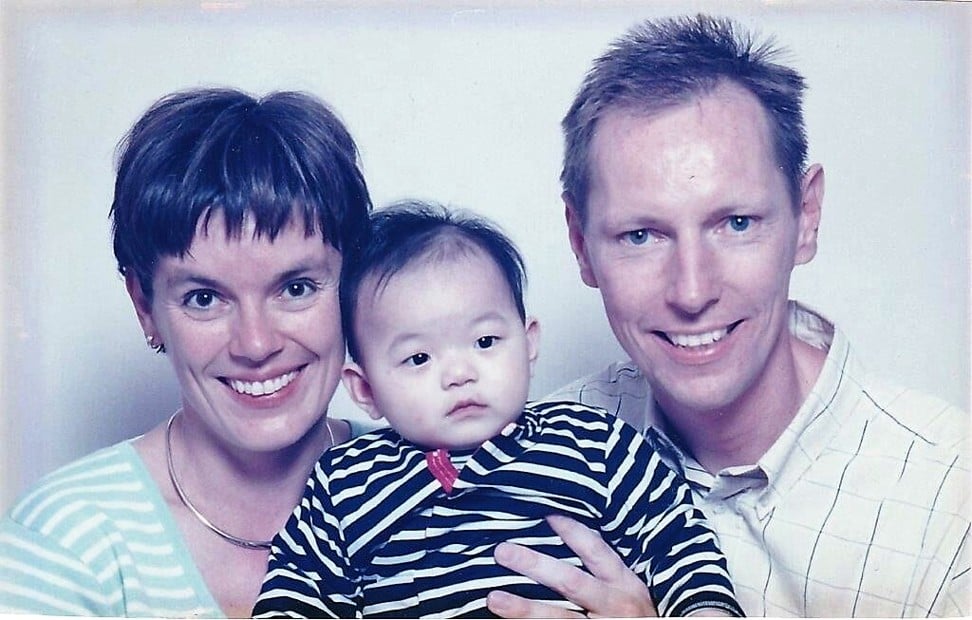

For Welberg, the separation that came to define her life occurred in 2001, when Wim and Mieke Welberg travelled to Gutian county, in Fujian province, in southern China, to adopt her. She was just a year old; her name Lin Shupin. The Welbergs named her Linde after the linden tree, known in the Netherlands for its resilience. They returned to China in 2004 to adopt a three-year-old boy from Jilin province, whom they named Tim.

Welberg was three years old when she began asking her adoptive parents to take her to China to find her blood relatives, but they insisted on waiting until she was older.

“During festivals, we threw flowers onto the river near our home. We told the kids the river would carry the flowers to China. It helped them feel connected to their homeland,” says Mieke Welberg, a nurse.

As she got older, Welberg began to have frequent emotional outbursts. “She drew pictures [of her biological parents] with tears on their cheeks. When she combed her long hair, she said her biological mother must have had long hair too,” Mieke Welberg says.

A year before Welberg was uprooted for a new life in the Netherlands, Susan and Jerry Fogg travelled to Feidong county, in the eastern province of Anhui, to adopt Lianna. They took the two-year-old back to Philadelphia and raised her along with their own five-year-old twins, Caitlyn and Joshua.

But by the age of 14, she was having a hard time fitting in. “I didn’t look American, but I didn’t feel Chinese either,” she says. “I wanted to find my roots and build my identity from my lost Chinese heritage.”

Throughout high school, Fogg saved money she earned from her part-time job at an ice cream parlour for a trip to China. Last year, when she turned 20, she intensified her search. With the help of a Chinese friend she met on Facebook, Fogg contacted the Feidong county government.

An official posted a notice about Fogg’s search on the county’s WeChat account, and asked her to mail over a DNA sample.

Within two weeks, three families had come forward for DNA testing. One sample, from a family surnamed Yang, matched Fogg’s. “They told me I had a brother and sister. I was super excited, but I also felt for the other two families who were still looking for their daughter,” she says.

On July 21, 2018, she boarded a plane bound for China. That same month, Welberg left the Netherlands on her own pilgrimage. At the age of six, her adoptive mother had told her about the one-child policy China introduced in 1979, during which parents with more than one child could be punished with heavy fines or lose their jobs. Millions of mothers had abortions and in many cases were sterilised.

Mieke told Linde that her biological mother could have chosen to terminate her pregnancy, but since she did not she would never forget her daughter. The Welbergs visited Gutian county twice, in 2011 and 2012, to look for their daughter’s biological family.

“Whenever I was on the streets of Gutian, I’d find myself staring at people’s faces, wondering if my parents were among them,” Linde Welberg says.

By 2017, the search for Linde’s birth parents had become a full-time job for her mother, who spent hours every day making connections on Chinese social media, using online translation tools to communicate.

I feel so much more content after our reunion. It has completed me. But I’m very aware that not everyone is so lucky

She posted a video of Linde reading an emotional letter to her birth parents on Weibo and streaming site Youku. The video went viral, and Chinese internet users began coming forward with information.

Linde submitted a sample of her DNA to a database in Gutian that claimed to have successfully matched hundreds of lost family members in China. The breakthrough came in April 2018 when one of her aunts saw a local news story about the case. Thinking the girl’s face looked familiar, she contacted the Zhangs, who submitted a DNA sample to the database. It was an exact match with Welberg’s.

In July, in an emotional reunion in the western province of Sichuan, where the Zhangs now live, Welberg met her birth family. She had just turned 18 years old.

“They hugged me. My mother cried. I was overwhelmed, confused but really happy. My dream had come true,” Welberg says.

After a banquet to celebrate their daughter’s homecoming, the families discussed their lives since the separation. Welberg’s biological parents explained that they had been impoverished when she was born and could not afford to provide for her. They left her outside the orphanage where she spent the first year of her life.

Welberg’s birth mother was devastated by her loss, saying it took her years to recover, and they had never stopped searching for her.

About 1,000km to the east, in Anhui, more than 50 relatives packed the family home to greet Fogg that same month. They gave her gifts, red packets filled with lucky money, and a new name: Yang Mengyuan, meaning dream fulfilled.

“The moment I saw my birth mum, my mind went blank,” Fogg says. “I’d replayed this scene in my mind so many times since I was 14. My mom was sobbing and kept repeating ‘sorry, sorry’. She held me so tight, as if she was afraid she’d lose me again.”

Over the following days, Fogg listened to her birth parents’ account of events leading up to the separation, and forgave them for the difficult decision they had been forced to make.

“I was aware of the preference for sons in Chinese culture, but didn’t feel bitter about it,” Fogg says. “I felt really close to my 16-year-old brother and relished my new role as the older sister.”

Welberg had a similar message for her birth parents. “I told them that my childhood in the Netherlands had been happy. I said I understood their situation and that I had forgiven them,” she says.

During her stay, Welberg’s birth parents lavished attention on her. “Whenever I coughed or got a mosquito bite, they’d try to take me to the doctor,” she says. Fogg’s new-found family were equally doting – a degree of attention that to the Westernised Fogg bordered on oppressive.

“Growing up in the US, I was taught to be independent, but here my Chinese parents were fussing over me,” she says. “They always wanted to give more food or drinks. They made sure I had an umbrella over my head when it was raining. They carried things for me when we went out,” Fogg says. “There were no boundaries.”

Yet Fogg says she appreciated her biological parents’ longing to make her feel part of the family. “They were loving and protective,” she says. “My father treated me as if I’d never left home.”

Welberg was also given a new name by her biological parents – Qiqi, meaning miracle. Since Welberg and Fogg returned to their adopted countries, they have communicated regularly with their Chinese families on WeChat.

Welberg is studying hotel management at De Rooi Pannen school in the Netherlands, but says she is planning to study Chinese in Chengdu – a promise she made to her biological parents.

Fogg, who is taking a degree course in global studies at Temple University in Pennsylvania, says she will return to see her birth parents in Anhui, and will invite them to visit the US.

“I feel so much more content after our reunion,” Welberg says. “It has completed me. But I’m very aware that not everyone is so lucky. More than anything I feel grateful, and my heart goes out to all the adoptees who are still searching.”

Both Lianna Fogg and Linde Welberg’s birth parents asked not to be named in this article.