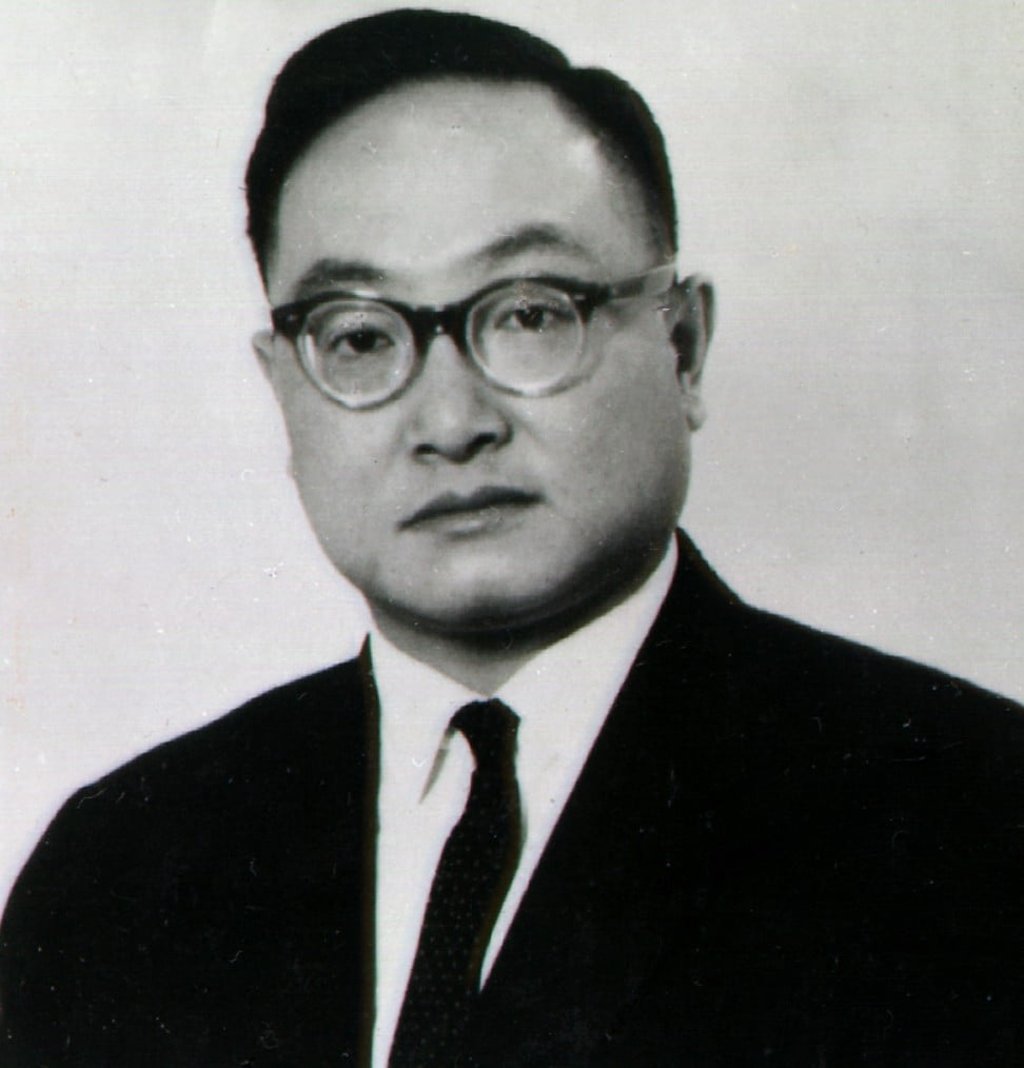

Why Hong Kong protests wouldn’t have fazed shipping tycoon Frank Tsao – a man ‘not easy to get close to’

- A titan of Asian shipping who died last month aged 94, Tsao’s early life was shaped by war and civil unrest in 1940s China

- Military conflict and political turmoil forced him to reinvent the family business in Hong Kong at the age of 24, where he faced further difficulties

The economic and social disruption in Hong Kong caused by months of protests has provoked several companies to issue public condemnations of violence and pleas for calm. However, the recent death of shipping magnate Frank Tsao Wen-king serves as a reminder that old-school local tycoons weren’t always daunted by upheaval and unrest.

Tsao was a classic Hong Kong tycoon, a titan of Asian shipping and an extremely wealthy individual, whose death last month at the age of 94 provoked an avalanche of tributes, from prime ministers to former employees.

In 2012, intelligence firm Wealth-X estimated his private fortune to be US$820 million. IMC Group, the company he founded in 1966, has more than 10,500 employees and contractors.

Tsao’s business philosophy was forged amid war and civil unrest, and the narrative of his early business life in Shanghai and Hong Kong would not look out of place in a bestselling novel.

“As far back as I can remember, Chinese society has almost always been in a state of instability and chaos,” Tsao wrote in his surprisingly candid autobiography, My Sixty Years – Turbulent Sailing, published by IMC in 2009.