How Parmesan, the famous Italian hard cheese, is produced to a medieval recipe, and aged for months or years

- Parmesan is loved everywhere, but the real thing is only made in northern Italy, using a centuries-old process and three ingredients: milk, salt and rennet

- The cheese is aged for between 12 and 72 months, and if quality inspectors are satisfied they certify it for sale as DOP Parmigiano Reggiano

You could be an Italian superstar chef like Massimo Bottura, crafting five different ages of Parmigiano Reggiano into a three-Michelin-star dish that includes a soufflé, a wafer and a mousse.

You could be a home chef, baking an aubergine Parmigiana or shaving cheese into a salad to give it a fabulous whack of umami.

Frustratingly, you could be dining in a restaurant where they ration the grated cheese like gold dust, hovering over your plate with a tiny spoon, whereas you’d much rather they just trusted you and left you the bowl.

That’s the beauty of Parmigiano Reggiano – we’ll call it Parmesan – a product that, wherever and however you eat it, only ever improves a dish.

Given its global renown and huge popularity, it’s still surprising to learn that authentic Parmesan cheese is only produced in a few small pockets around the northern Italian cities of Parma, Reggio Emilia, Modena, Mantua and Bologna.

When we say authentic, we mean Parmesan cheese stamped DOP, which stands for Denominazione d’Origine Protetta and in Italian denotes a product with a protected designation of origin – certification that it was produced in a specific region using traditional production methods.

Eating avocados twice a week could cut heart disease risk by a fifth: study

The history of Parmesan cheese goes back to the 12th century when Benedictine monks were looking for ways to conserve milk.

While it may taste similar today to how it did then, the production process has been brought well and truly up to date.

Milk comes from local cows whose diet is strictly governed, combining around 80 per cent alfalfa with other cereals and pulses, all locally grown. It’s said that special bacteria in these feeds allows the cheese to mature without needing additives or preservatives.

42,000 litres of it fill 42 vast copper cauldrons, each of which produces two wheels of Parmesan, meaning that it takes 500 litres of milk to make one 40kg wheel.

My guide explains that the milk first stands overnight to let the cream rise to the top, before it is removed and turned into butter. The remaining, partially skimmed milk is mixed with whole milk and heated before calf rennet is added; the magic ingredient curdles and coagulates the milk in less than 24 hours.

Workers then manoeuvre into place a huge wooden-handled whisk called a spino to break up the curds. Next, the curds are lifted into a muslin cloth that is squeezed, then tied around a steel pole before it is cut in two using a huge blade.

My guide interjects, keen to stress that the fine-meshed muslin is completely natural, adding: “Everything in the Parmigiano Reggiano production process has to be natural.”

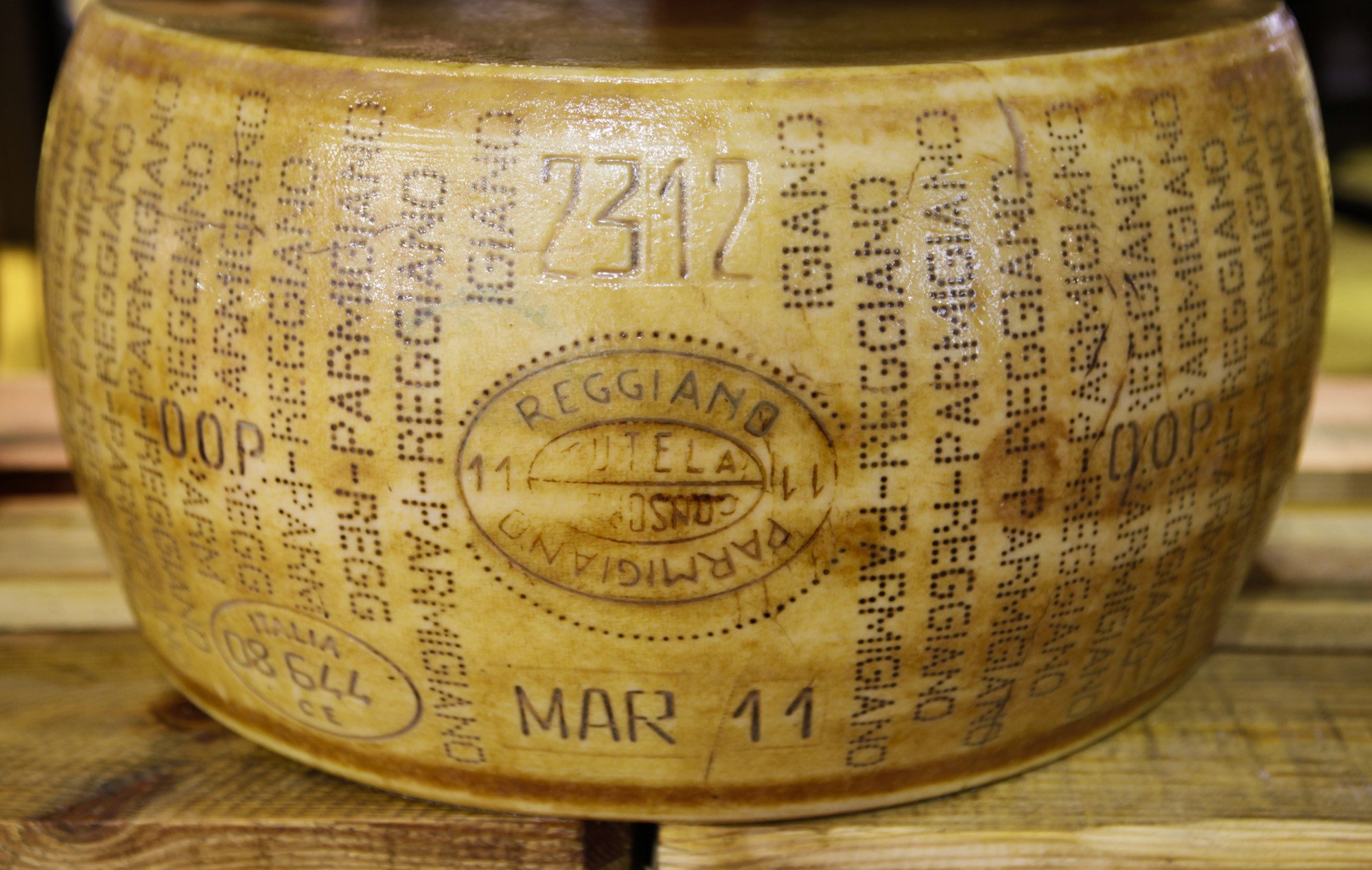

Next, the curds are pressed into lockable metal moulds that form them into the distinctive wheel shape. A few days later plastic bands are used to imprint the intriguing code-like markings that you see on the rind of the Parmesan wheel, discernible even if you’ve bought just a small wedge at the supermarket.

These symbols contain a wealth of information, including exactly when and where the cheese was produced, the registration of the dairy and the official seal of a local consortium. In a world where counterfeits abound, it’s a crucial element of traceability.

The penultimate stage, salting, comes once they start “breathing” and have begun to form their own rind.

The wheels are immersed for three weeks in water containing Sicilian salt. Through osmosis, the salt is taken on and whey left over as a by-product, something that was traditionally fed to local pigs used to produce prosciutto di Parma. My guide explains: “These cheeses are so big, it’s a gentle way to get them salted.”

It’s the ageing process that sees my jaw hit the floor. We are led into a vast, high-ceilinged building lined from bottom to top (a height of more than 24 metres, or 80 feet) with huge shelves made from Slovenian poplar that hold thousands of wheels of cheese. Inside this dairy cathedral, with its powerful aroma, the cheese wheels mature for between 12 and 72 months.

“The 12-month tastes of milk, the 24-36 months are a little bit spicier,” one of the co-operative’s master cheesemakers explains.

“The 24-month has a good balance, you can grate it, cook dishes and eat chunks of it. At more than 30 months, it’s clearly grainy in texture, highly digestible, quite savoury and you can perceive all the aromas of the milk.

“When you reach 72 months, it’s special, really the maximum – I did try one which was aged for 16 years. Let’s just say it was more of a souvenir than a cheese!”

The graininess in Parmesan comes from milk protein crystals, something that many consumers wrongly – but understandably – assume is salt. The more grains there are, the more the proteins have been broken down, and the easier it is to digest.

Back in the enormous ageing sheds, cheese-flipping robots glide silently down corridors extracting and turning the heavy wheels. It’s astonishing to learn that until relatively recently, this process was done by hand.

After 12 months of maturation, an expert from the consortium checks the cheeses, tapping every one with a small hammer. The sounds which emanate reveal any defects or lactic mistakes such as air bubbles, although to the untrained ear they all sound very similar.

Only when the expert is happy can the wheel receive a branded stamp enabling it to be officially sold as Parmigiano Reggiano.

Arepas, hallacas – dishes of Venezuela explained by its first Michelin chef

This cooperative produces 230 wheels of cheese every 24 hours. The output allows it to replenish its vast storerooms; in common with many DOP foods, demand exceeds supply. Some 85 per cent of what it produces is exported.

I ask one of the employees, who has been working on dairy farms for more than 40 years – and comes from generations of cheesemakers – whether he doesn’t get just a little bit bored of eating Parmigiano?

With a look that mixes disbelief and horror, he says: “No! I eat it every day – and a lot! Normally grated on pasta, but also in chunks.”