Philippines’ poorest hit hardest by birth control failings, ‘toothless’ family planning law and interference from church

The Catholic Church and conservative politicians have helped to ensure abortion and divorce remain illegal, and the Philippines’ mostly Catholic population is booming, despite birth control legislation

At age 33 and raising six children in a slum named “Paradise Village”, Myrna Albos is Exhibit A for the Philippines’ serial family planning failures.

The plumber’s wife already had four children by the time a family planning law was passed in December 2012, but she had two more after opponents blocked it and the nearby government health centre ran out of birth control pills.

“I don’t want any more [children]. Sending all of them to school is an effort. One more and I may no longer have time for myself,” the former department store clerk says.

Albos and her family live on her husband’s US$10-a-day wage in a dirt-floor home in Paradise Village, tucked behind a smelly open sewer in the north of Manila, the nation’s capital where millions live in brutal poverty.

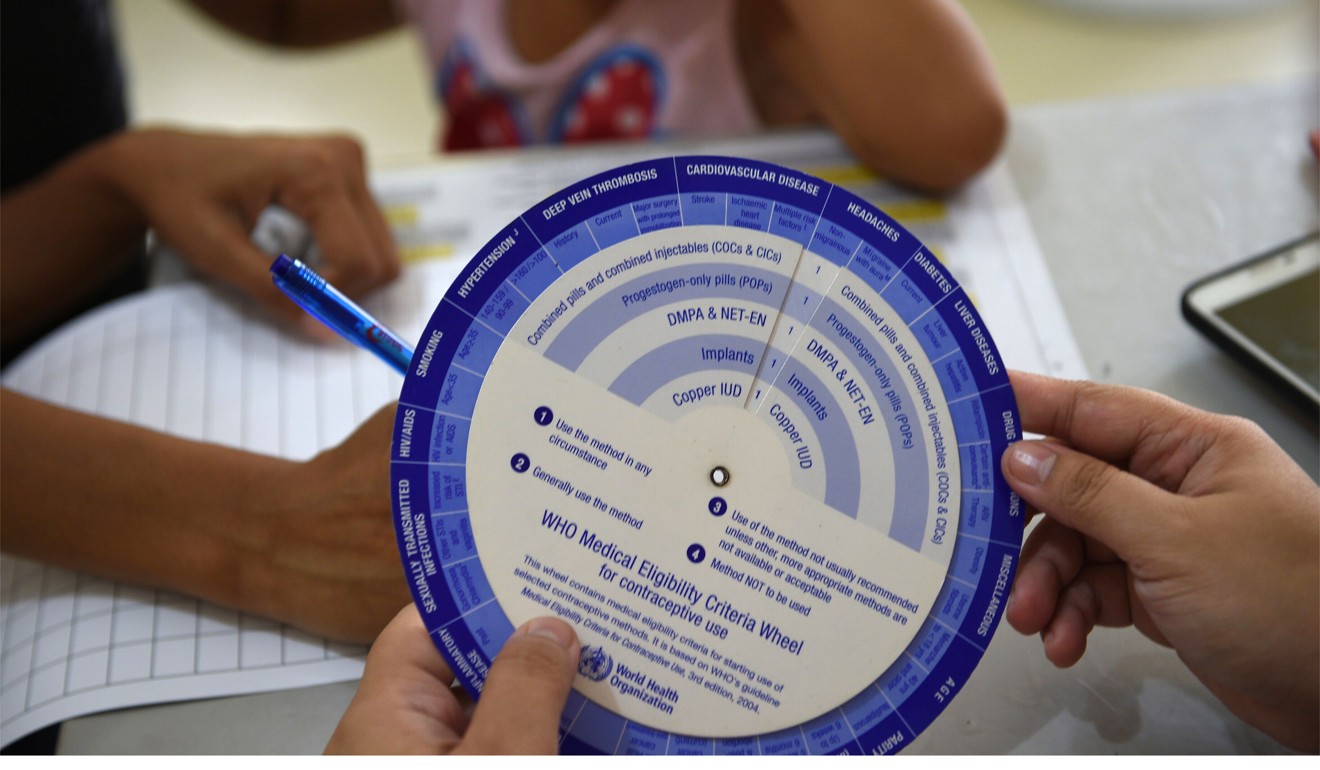

The law was meant to provide free condoms, birth control pills, contraceptive implants and other family planning methods to couples in poor communities, while protecting mothers from death and other health risks associated with pregnancy and childbirth.

Bishops pledge to continue Philippine birth control fight

The law was hailed then as a big victory for the rights of the poor, finally overcoming the powerful Catholic Church and its socially conservative allies in congress.

The Philippines, a former Spanish colony, is the Catholic Church’s Asian bastion with 80 per cent of the nation’s 103 million people being Catholic. The power of the church has helped to ensure abortion and divorce remain illegal.

The country’s fertility rate slowed to 2.33 births per woman in 2015 from a runaway six in the 1970s, United Nations data shows. The number of Filipinos who die from complications of giving birth also remains high, according to the UN figures.

However the legislation turned out to be only the start of another long battle. The law itself did not come into force until April 2014, as it was delayed by legal challenges.

While the Supreme Court ruled the legislation was constitutional, it weakened the law by removing penalties for officials and workers who refused to provide contraceptives. It was weakened further after conservative legislators gutted its funding. “We have not taken off. We’ve been taxiing for the last five years,” Health Undersecretary Gerardo Bayugo says, when asked to assess the programme.

He says the Supreme Court’s removal of the penalty provisions had rendered the law “basically toothless”, while a lack of funds meant the government could not buy enough contraceptives. President Rodrigo Duterte, who took office last year, has followed in his predecessor’s footsteps in trying to get contraceptives to the masses.

His Food and Drug Administration this month ruled that dozens of contraceptives, including implants and pills, were not abortion-inducing and thus the government could distribute them for free.

Two surprising health benefits of the pill, unrelated to birth control, discovered

Condoms were not subject to the challenge but only two per cent of Filipino men use them, according to the health department. This is partly due to men not wanting to use them, and their expense.

Church-backed groups filed a case with the Supreme Court in 2015 insisting the implants and other contraceptives were abortifacients, and thus unconstitutional. The Supreme Court then ordered the government not to distribute those contraceptives until the FDA made its own ruling on the issue.

Bayugo says the government had started to deliver 500,000 implants, the vast majority of its stocks, following this month’s FDA ruling. But he says it was not nearly enough to tackle the problem. “The resolution will not cure the funding issue … it’s been our problem for the last five years,” he says.

The health department estimates six million couples need contraceptives, but have no reliable access to them.

This year’s allocated budget of 165 million pesos (US$3.2 million) is only enough for two million couples, according to Bayugo. Congress rejected the original family planning budget proposal for 2017 of 1.2 billion pesos.

The health ministry has sought a budget of 342 million pesos for next year. But this is still less than a third of what the government deemed necessary to fully implement the law. And with less than five weeks left in 2017, congress has yet to approve next year’s family planning budget.

Must you completely clear your system of birth control pills before getting pregnant?

While the government was banned from dispensing implants, Albos the slum mother, went to Likhaan, a charity that receives foreign funding. She finally had an implant, which releases a hormone that prevents women’s ovaries from releasing eggs, after her sixth child was born this year.

But even their own modest programmes have suffered setbacks that highlight the enduring political problems. Last year scores of panicked women swamped Manila clinics demanding the removal of their hormone implants, Melgar says. The incidents were confirmed by Bayugo.

The women were scared off by a politician’s unfounded warnings the implants caused cancer, polio and even blindness, they said.

.png?itok=arIb17P0)